It Wakes in Me (25 page)

Authors: Kathleen O'Neal Gear

THE ANASAZI MYSTERY SERIES

The Visitant

The Summoning God

Bone Walker

The Summoning God

Bone Walker

THE FIRST NORTH

AMERICANS SERIES

AMERICANS SERIES

People of the Wolf

People of the Fire

People of the Earth

People of the River

People of the Sea

People of the Lakes

People of the Lightning

People of the Silence

People of the Mist

People of the Masks

People of the Owl

People of the Raven

People of the Moon

People of the Nightland*

People of the Weeping Eye*

People of the Fire

People of the Earth

People of the River

People of the Sea

People of the Lakes

People of the Lightning

People of the Silence

People of the Mist

People of the Masks

People of the Owl

People of the Raven

People of the Moon

People of the Nightland*

People of the Weeping Eye*

BY KATHLEEN O’NEAL GEAR

Thin Moon and Cold Mist

Sand in the Wind

This Widowed Land

It Sleeps in Me

It Wakes in Me

It Dreams in Me*

Sand in the Wind

This Widowed Land

It Sleeps in Me

It Wakes in Me

It Dreams in Me*

BY W. MICHAEL GEAR

Long Ride Home

Big Horn Legacy

The Morning River

Coyote Summer

The Athena Factor

Big Horn Legacy

The Morning River

Coyote Summer

The Athena Factor

OTHER TITLES BY

KATHLEEN O’NEAL GEAR

AND W. MICHAEL GEAR

KATHLEEN O’NEAL GEAR

AND W. MICHAEL GEAR

Dark Inheritance

Raising Abel

Raising Abel

*Forthcoming

www.Gear-Gear.com

www.Gear-Gear.com

Sigmund Freud was not the first person to discover that dreams can give us clues about illness. Many North American tribes, particularly Iroquoian and Algonquian peoples, believed that dreams were the language of the soul, and that the unfulfilled desires of the soul, as represented in dreams, could cause illness, or even death. To make certain this didn’t happen, the entire community worked together to fulfill the dreams of sick people.

The

andacwander

, as those of you who read

It Sleeps in Me

know, is real.

andacwander

, as those of you who read

It Sleeps in Me

know, is real.

The only detailed description of this healing ritual comes from Father Gabriel Sagard, who lived among the Huron tribe from 1623 to 1624. He was part of an apostolic ministry to the Huron and was very dedicated to the task of converting them to Christianity. In the process, he recorded his observations, his trials and tribulations, his successes and failures, and published them in 1632. His book,

Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons,

was so popular that it had to be reprinted, which it was in l636. However, it came out under the new title of

Histoire du Canada,

and contained several elaborations on the original work.

Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons,

was so popular that it had to be reprinted, which it was in l636. However, it came out under the new title of

Histoire du Canada,

and contained several elaborations on the original work.

Certainly one of the most spectacular sections of

Le grand voyage

is Chapter X, where he recounts witnessing several sexual healing rituals, particularly the

andacwander.

Le grand voyage

is Chapter X, where he recounts witnessing several sexual healing rituals, particularly the

andacwander.

Because he was not a member of the community, Sagard was forbidden to participate, or even look upon the ritual, but fortunately for us, he watched it through a chink in the walls of a longhouse.

It is especially interesting to me that Sagard only mentions

dances “ordered on behalf of a sick woman.” Did he simply never see the

andacwander

performed for a sick man, or were sexual healing rituals largely women’s rituals? Jesuit references suggest that men were also cured in this manner (Thwaites 1896–1901, 17: 179), so it’s possible that Sagard only watched ceremonies for women, which is interesting in and of itself.

dances “ordered on behalf of a sick woman.” Did he simply never see the

andacwander

performed for a sick man, or were sexual healing rituals largely women’s rituals? Jesuit references suggest that men were also cured in this manner (Thwaites 1896–1901, 17: 179), so it’s possible that Sagard only watched ceremonies for women, which is interesting in and of itself.

In any case, the Huron worked very hard to heal the sick members of their community. Even when it went against their most basic social beliefs of propriety, they tried, by acting out the sick person’s dreams, to fulfill the desires of her soul. Sagard wrote, “ … for they prefer to suffer and be in want of anything rather than to fail a sick person at need” (Wrong, p. 118).

During the

andacwander

, the unmarried people in the village assembled in the sick person’s house and had sexual intercourse while the patient watched and two shamans shook tortoiseshell rattles and sang. Sometimes, the sick person requested one of the young people to have sex with her. Based upon dreams, other types of requests were also made. Sagard describes one instance in which a sick woman asked one of the young men to urinate in her mouth. He wrote: “ … a feature I cannot excuse nor pass over silently—one of those young men was required to make water in her mouth, and she had to swallow it, which she did with great courage, hoping to be cured by it; for she herself wished it all to be done in that manner, in order to carry out without any omission a dream she had had” (Wrong, p. 118).

andacwander

, the unmarried people in the village assembled in the sick person’s house and had sexual intercourse while the patient watched and two shamans shook tortoiseshell rattles and sang. Sometimes, the sick person requested one of the young people to have sex with her. Based upon dreams, other types of requests were also made. Sagard describes one instance in which a sick woman asked one of the young men to urinate in her mouth. He wrote: “ … a feature I cannot excuse nor pass over silently—one of those young men was required to make water in her mouth, and she had to swallow it, which she did with great courage, hoping to be cured by it; for she herself wished it all to be done in that manner, in order to carry out without any omission a dream she had had” (Wrong, p. 118).

The more scholarly-minded among you will be asking, “Why is a Huron ritual being used to describe a prehistoric Mississippian mound-builder culture in Florida?”

First, linguistically, Huron is closely related to Cherokee, and based upon a comparison of grave goods, chambered burial pits, earth-covered ceremonial structures, and the striking similarity of gorget styles, I think a strong argument can be made for a persistent social tradition from the Mississippian

cultural patterns represented in the Pisgah phase in the Appalachian summit region to the Qualla phase of the Cherokee. Historic Cherokee Middle Towns are located within the Pisgah archaeological sphere and, as Dickens notes (1976, p. 213), there are many “carry-over traits” between the cultures.

cultural patterns represented in the Pisgah phase in the Appalachian summit region to the Qualla phase of the Cherokee. Historic Cherokee Middle Towns are located within the Pisgah archaeological sphere and, as Dickens notes (1976, p. 213), there are many “carry-over traits” between the cultures.

Secondly, at the point of historic contact with European cultures, the

andacwander,

or modified versions of it, had spread from Iroquoian to Algonquian tribes (Hickerson, 1960), indicating the remarkable power the ritual possessed. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to assume that the origins of this particular soul-curing ritual extend into prehistoric times.

andacwander,

or modified versions of it, had spread from Iroquoian to Algonquian tribes (Hickerson, 1960), indicating the remarkable power the ritual possessed. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to assume that the origins of this particular soul-curing ritual extend into prehistoric times.

Lastly, I know of no other fictional attempt to see this sacred ritual through the eyes of the people who practiced it, and I think it’s important to make that attempt.

The

andacwander

, after all, was a supreme act of generosity.

andacwander

, after all, was a supreme act of generosity.

Davis, Dave D.

Perspectives on Gulf Coast Prehistory.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida/Florida State Museum, 1984.

Perspectives on Gulf Coast Prehistory.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida/Florida State Museum, 1984.

Dickens, Roy S., Jr.

Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Gilliland, Marion Spjut.

The Material Culture of Key Marco, Florida.

Port Salerno: Florida Classics Library, 1989.

The Material Culture of Key Marco, Florida.

Port Salerno: Florida Classics Library, 1989.

Hickerson, Harold. “The Feast of the Dead Among the Seventeenth-Century Algonkians of the Upper Great Lakes.”

American Anthropologist

62:81–107.

American Anthropologist

62:81–107.

Hudson, Charles.

The Southeastern Indians.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989.

The Southeastern Indians.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989.

Kilpatrick, Jack Frederick, and Anna Gritts Kilpatrick.

Notebook of a Cherokee Shaman

. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Vol. 2, Number 6. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1970.

Notebook of a Cherokee Shaman

. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology, Vol. 2, Number 6. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1970.

———.

Walk in Your Soul: Love Incantations of the Oklahoma Cherokees.

Dallas: Southern Methodist University, 1965.

Walk in Your Soul: Love Incantations of the Oklahoma Cherokees.

Dallas: Southern Methodist University, 1965.

———.

Run Toward the Nightland: Magic of the Oklahoma Cherokees.

Dallas: Southern Methodist University, 1967.

Run Toward the Nightland: Magic of the Oklahoma Cherokees.

Dallas: Southern Methodist University, 1967.

Lewis, Barry, and Charles Stout, eds.

Mississippian Towns and Sacred Space: Searching for an Architectural Grammar.

Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

Mississippian Towns and Sacred Space: Searching for an Architectural Grammar.

Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

McEwan, Bonnie G.

Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Milanich, Jerald T.

Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994.

Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994.

———.

McKeithen Weeden Island: The Culture of Northern Florida, A.D. 200

–

900.

New York: Academic Press, 1984.

McKeithen Weeden Island: The Culture of Northern Florida, A.D. 200

–

900.

New York: Academic Press, 1984.

———.

The Timucua.

Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

The Timucua.

Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

———.

Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995.

Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995.

Milanich, Jerald T., and Charles Hudson.

Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1993.

Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1993.

Neitzel, Jill E.

Great Towns and Regional Polities in the Prehistoric American Southwest and Southeast.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Great Towns and Regional Polities in the Prehistoric American Southwest and Southeast.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Purdy, Barbara A.

The Art and Archaeology of Florida’s Wetlands.

Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1991.

The Art and Archaeology of Florida’s Wetlands.

Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1991.

Sears, William H.

Fort Center: An Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1994.

Fort Center: An Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1994.

Swanton, John R.

The Indians of the Southeastern United States.

Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

The Indians of the Southeastern United States.

Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

Thwaites, Reuben G.

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents,

Vol. 17. Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Co., 1896.

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents,

Vol. 17. Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Co., 1896.

Trigger, Bruce G.

The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660.

Montrèal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987.

The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660.

Montrèal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987.

Walthall, John A.

Prehistoric Indians of the Southeast

:

Archaeology of Alabama and the Middle South.

Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Prehistoric Indians of the Southeast

:

Archaeology of Alabama and the Middle South.

Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Willey, Gordon R.

Archaeology of the Florida Gulf Coast.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1949.

Archaeology of the Florida Gulf Coast.

Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1949.

Wrong, George M.

Sagard’s Long Journey to the Huron Country.

Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1939.

Sagard’s Long Journey to the Huron Country.

Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1939.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

IT WAKES IN ME

Copyright © 2006 by Kathleen O’Neal Gear

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A Forge Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Forge

®

is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

®

is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

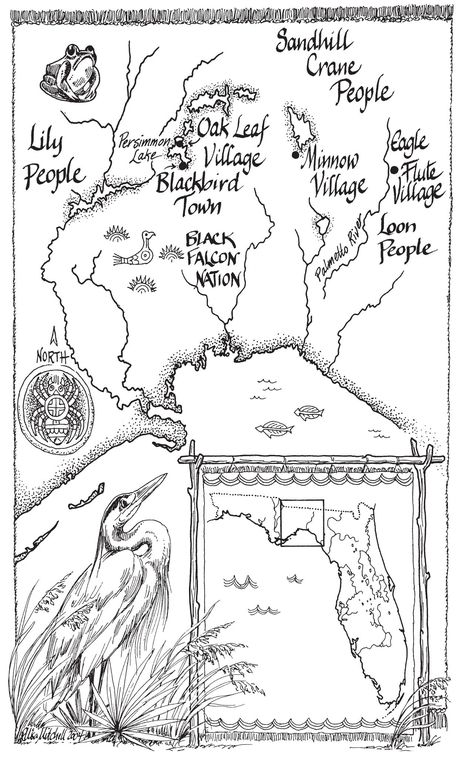

Map and chapter ornaments by Ellisa Mitchell

eISBN 9781466815629

First eBook Edition : March 2012

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gear, Kathleen O’Neal.

It wakes in me / Kathleen O’Neal Gear.

p. cm.

“A Tom Doherty Associates book.”

ISBN 0-765-31482-7

EAN 978-0-765-31482-6

1. Indians of North America—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3557.E18I89 2006

813’.54—dc22

2005032799

First Edition: July 2006

Other books

Billy the Kid by Theodore Taylor

Kolchak The Night Strangler by Matheson, Richard, Rice, Jeff

Keegan's Bride (Mail Order Brides of Texas 2) by Kathleen Ball

Cornucopia by Melanie Jackson

The Fall by Christie Meierz

Madness Under the Royal Palms by Laurence Leamer

Dos monstruos juntos by Boris Izaguirre

All the Time in the World by E. L. Doctorow

The Mist by Dean Wesley Smith, Kristine Kathryn Rusch

A Maine Christmas...or Two by J.S. Scott and Cali MacKay