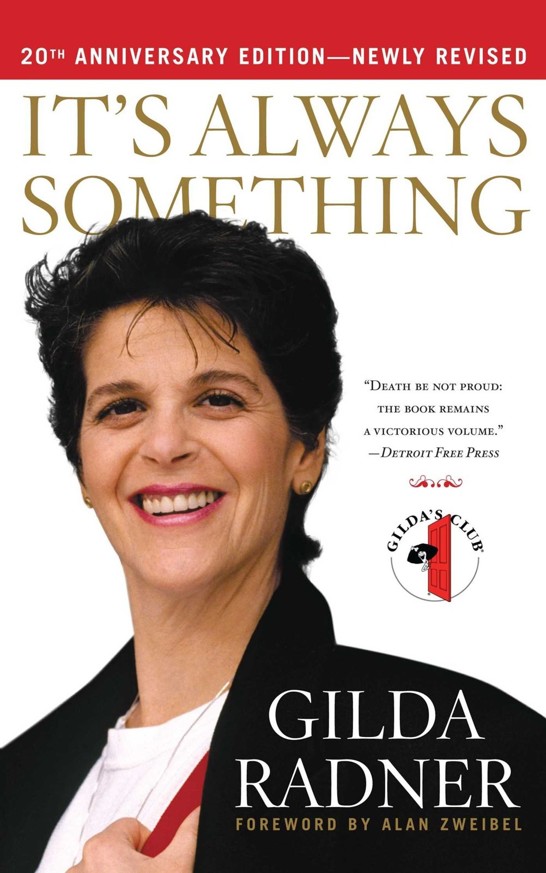

It's Always Something

Read It's Always Something Online

Authors: Gilda Radner

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To my dear husband, Gene Wilder

My thanks to my literary agent, Esther Newberg, for her feisty belief in me; to Susan Kamil, for opening the door into the world of publication; to Hillary Johnson, for listening to my tale over many lunches, while stirring her tea and my mind; to Rachel McCallister, for protecting me from enquiring claws; and to Bob Bender, my gentle and splendid editor.

Thanks to Bonnie Sue Smith and Anne Leffingwell, my West and East Coast typists; and finally, to Grace Ayrsman, who kept my desk and my soul in order.

W

e had so much fun.

Gilda and I were hired to be a part of a new show, to be called “Saturday Night Live,” and the time we spent together was dedicated to comedy. Writing jokes and creating characters. And boy, it was fun. The mid-’70s. Two kids roaming the streets of New York at a time when everyone seemed to be our age. Fellow boomers who shared our life experiences during the same cultural revolution. We’d take subways and long walks and even longer dinners where we’d bring legal pads and try our best to make each other laugh. And if we did, we wrote it down. And if it made our “SNL” colleagues laugh, Lorne Michaels put it on television. The success of the show put us in the company of famous people and allowed us to enter rooms where parties were taking place. We took none of it too seriously—it was a ride we tried to enjoy without losing our sense of wonder.

Then adulthood set in. Grown-up things like marriages and mortgages and careers that no longer involved each other put our friendship to a test across a country that now separated us. She in Los Angeles and I in New York in a pre-Internet world where handwritten letters and late-night phone calls did their best to keep us connected. But inevitably we drifted apart.

When I co-created a television show in 1986 that required me to move to California, I called Gilda. In an attempt to revive a dormant relationship, I would ask her out; she’d accept, and then break the date at the last minute. Time and again this happened and I got angry. She explained that she was sick. That her mind wanted to do things that her body no longer allowed her to do. The doctors called it Epstein-Barr virus and said it would have to run its course. When it was correctly diagnosed as ovarian cancer, a heroic Gilda emerged. She used her fame to shine a light on her sickness and show the world that you can lead a quality life by dealing with it head-on. She looked it straight in the eye and dared it to get the better of her. To prove her point, she went to Lakers basketball games, appeared on the cover of

Life

magazine, and made cancer jokes on

It’s Garry Shandling’s Show.

Her illness drew us closer. My job was to make her laugh. To take her mind off what was happening to her. Yet one night, during a quiet walk along a California beach, she told me she would have preferred to be a ballerina; that comedy was about what was wrong with the world—people laughed because something was too big, or too small, or too much, or not enough. Quirks and exaggerations were the essence of parody. Irony and discomfort the grist for humor. But ballet was about harmony. Poetry in controlled motion. A finely tuned, musically carried body at peace with all that surrounds it.

Gilda’s contribution straddles both worlds. Her comedy still makes people laugh whether she’s loud as Roseanne Roseannadanna or running around like the little girl with whom she was always in touch. At the same time, her pleas for early detection, urgings to celebrate all of life’s delicious ambiguities, and legacy of Gilda’s Club help people find the ballet in their own lives. I think she would be pleased.

Alan Zweibel

New York, N.Y.

May 2009

I

started out to write a book called

A Portrait of the Artist as a Housewife.

I wanted to write a collection of stories, poems, and vignettes about things like my toaster oven and my relationships with plumbers, mailmen and delivery people. But life dealt me a much more complicated story. On October 21, 1986, I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Suddenly I had to spend all my time getting well. I was fighting for my life against cancer, a more lethal foe than even the interior decorator. The book has turned out a bit differently from what I had intended. It’s a book about illness, doctors and hospitals; about friends and family; about beliefs and hopes. It’s about my life, especially about the last two years. And I hope it will help others who live in the world of medication and uncertainty.

These are my experiences, of course, and they may not necessarily be what happens to other cancer patients. All the medical explanations in the book are my own, as I understand them. Cancer is probably the most unfunny thing in the world, but I’m a comedienne, and even cancer couldn’t stop me from seeing humor in what I went through. So I’m sharing with you what I call a seriously funny book, one that confirms my father’s favorite expression about life, “It’s always something.”

A man traveling across a field encountered a tiger. He fled, the tiger after him. Coming to a precipice, he caught hold of the root of a wild vine and swung himself down over the edge. The tiger sniffed at him from above. Trembling, the man looked down to where, far below, another tiger was waiting to eat him. Only the vine sustained him.

Two mice, one white and one black, little by little started to gnaw away the vine. The man saw a luscious strawberry near him. Grasping the vine with one hand, he plucked the strawberry with the other.

How sweet it tasted!

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings,

Compiled by Paul Reps

The Marriage

L

ike in the romantic fairy tales I always loved, Gene Wilder and I were married by the mayor of a small village in the south of France, September 18, 1984. We had met in August of 1981, while making the movie

Hanky Panky

, a not-too-successful romantic adventure-comedy-thriller. I had been a fan of Gene Wilder’s for many years, but the first time I saw him in person, my heart fluttered—I was hooked. It felt like my life went from black and white to Technicolor. Gene was funny and athletic and handsome, and he smelled good. I was bitten with love and you can tell it in the movie. The brash and feisty comedienne everyone knew from “Saturday Night Live” turned into this shy, demure ingenue with knocking knees. It wasn’t good for my movie career, but it changed my life.

Up to that point, I had been a workaholic. I’d taken one job after another for over ten years. But just looking at Gene made me want to stop . . . made me want to cook . . . made me want to start a garden . . . to have a family and settle down. To complicate things, I was married at the time and Gene had been married and divorced twice before and was in no hurry to make another commitment. I lived in a house I had just bought in Connecticut and he lived in Los Angeles. I got an amicable divorce six months later and Gene and I lived together on and off for the next two-and-a-half years. My new “career” became getting him to marry me. I turned down job offers so I could keep myself geographically available. More often than not, I had on a white, frilly apron like Katharine Hepburn in

Woman of the Year

when she left her job to exclusively be Spencer Tracey’s wife. Unfortunately, my performing ego wasn’t completely content in an apron, and in every screenplay Gene was writing, or project he had under development, I finagled my way into a part.

We were married in the south of France because Gene loved France. If he could have been born French, he would have been—that was his dream.

The only time I had been to France was when I was eighteen. I went with a girlfriend in the sixties when it was popular to go for less than five dollars a day—of course, your parents still gave you a credit card in case you got in trouble. We went on an Icelandic Airlines flight. The plane was so crowded, it seemed like there were twelve seats across and it tilted to whatever side the stewardess was serving on.

We landed in Luxembourg and then our next stop was Brussels. My girlfriend was of Polish descent, but had been born in Argentina—she spoke four languages fluently. After four days, she was sick of me saying, “What?,” “What did they say?”—she couldn’t stand me. She just wanted to kill me. I was miserable all through the trip. I was miserable in Luxembourg. I was miserable in Brussels. We slept at the University of Brussels; you could stay there for a dollar a night in the student dormitory, where we spent the evening watching the movie

Greener Pastures

with French subtitles. We went on to Amsterdam where we stayed in a youth hostel. I’ll never forget that there was pubic hair on the soap in the bathroom and it made me sick. Years later, I had Roseanne Roseannadanna talk about it.

There I was, eighteen years old in Europe, and all the terrible things that happen to tourists happened to me. In Amsterdam I lost my traveler’s checks and spent one whole day looking for the American Express office. I was so upset by the Anne Frank House that I got horrible diarrhea in the lobby of the Rembrandt Museum and never saw one painting. When we went on to France, my girlfriend’s boyfriend met us in Paris—romantic Paris! I found the city hectic and weird. Plus, I was on my own. My friend was with her boyfriend; I was the third person—the girl alone.

I don’t know why, but everywhere I went, everywhere I looked, a man would be playing with himself. I always have been a starer—a voyeur. I must have been staring too much at other people because I would always get in trouble. I’d be waiting to sit down in a restaurant and a man would come out of the restroom (this must have happened about four or five times), and he would suddenly start staring at me and undoing his fly and playing with himself. Yuck! This wasn’t the romantic Paris I had heard of.

I was very isolated because of the language barrier. I felt lonelier than I had ever been. One night after a terrible less-than-two-dollar dinner, I actually ended up running out into the middle of the Champs Elysées trying to get hit by traffic. Yeah, I ran out onto the boulevard and lay down on the ground before the cars came whipping around the corner—you wouldn’t believe how fast they come around there. My girlfriend’s boyfriend ran out and dragged me back. I was lying down in the street waiting to get run over because I was so lonely and he picked me up and dragged me back. The next day I made a reservation on Air France first class to go home. I only stayed two weeks and spent a fortune flying home. I never went back until Gene took me in 1982. It was the first summer we were living together, and Gene couldn’t wait to show me Paris and the French countryside and the southern provinces of the country he adored.

Gene reintroduced Europe to me; and with him I learned it could be a pleasure and I could love it. He took me to one particular château in the mountains in the south of France. We stayed two weeks and I discovered that traveling can be wonderful if you stop to enjoy where you are. Our room was luxurious, with a spectacular view of the Riviera. There was a tennis court and a pool and a restaurant that had one star in the Michelin guidebook. Food was served like precious gems, and I remember we watched the French Open tennis tournament on television in our splendid room, in French. Mats Wilander won.