J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (36 page)

Read J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets Online

Authors: Curt Gentry

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #United States, #Political Science, #Law Enforcement, #History, #Fiction, #Historical, #20th Century, #American Government

Homer Cummings had insisted on a strict chain of command but helped create a publicity empire that gave the FBI, rather than the Justice Department, most of the credit in the war against crime, in the process diminishing the attorney general’s importance while elevating the FBI director to near-legendary status. Frank Murphy let Hoover have his own way, so long as he could share the spotlight. Robert Jackson opposed Hoover on such issues as wiretapping, then was forced to reverse himself when the president sided with the FBI director. By contrast, although he often criticized Biddle privately—his prosecutive policy was too soft, he complained to his aides—Hoover was “truly comfortable” with this attorney general, who remained in office until Roosevelt’s death in 1945.

15

Biddle opposed wiretapping in principle—but not in practice. “I thought, and still think,” Biddle wrote in his autobiography, “that wiretapping is a ‘dirty business,’ but no dirtier than the use of stool pigeons, or undercover men, or informers. Of course it violates privacy; but it is an extraordinarily effective tool in running down crime.” Unlike Jackson, who had washed his hands of the whole matter, Biddle studied each wiretap application carefully, “sometimes requesting more information, occasionally turning them down when [he] thought they were not warranted.”

*

16

This hampered Hoover not at all. If refused a tap, he could substitute a bug, since, by his interpretation, microphone surveillance did not require the attorney general’s permission.

In 1943 Attorney General Biddle discovered, and reviewed, the Custodial Detention list, finding it “impractical, unwise, dangerous, illegal and inherently unreliable,” and ordered Hoover to abolish it.

18

He did,

semantically,

by changing its name to the Security Index and instructing his aides to keep its existence secret from the Justice Department. But it was Biddle who, as the nation’s chief lawyer, approved the forced internment of 110,000 Japanese-Americans—70,000 of them U.S. citizens by birth—in barbed-wire-enclosed “relocation” camps.

(Hoover opposed the internment not on First Amendment grounds, as has often been maintained, but because he believed the most likely spies had already been arrested, by the FBI, in the first twenty-four hours after Pearl

Harbor. Thus the relocation was, in Hoover’s view, an implied criticism of the Bureau’s efforts. After the war Hoover’s opposition was much publicized. Nothing was said, however, about the FBI director’s 1938-40 memorandums warning FDR that both the Nazis and the Soviets had planted secret agents among the Jewish refugees, nor was any publicity given to Hoover’s opposition to relaxing immigration quotas for European Jews, many of whom, he was convinced, were Communists.)

Biddle opposed the Alien Registration Act (or Smith Act), passed in June 1940, with Hoover’s strong backing.

*

But he did so only in retrospect, for he prosecuted the first twenty-nine defendants.

When Jackson left the AG’s office, Biddle inherited the Harry Bridges deportation case. While admitting that the evidence of the labor leader’s Communist party membership “was not overwhelming,” Biddle nevertheless, with Hoover’s prodding, pursued the matter all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

19

Moreover, he found himself defending the FBI director when Bridges caught two of his agents in a most compromising situation.

“Just the mention of the name Harry Bridges was enough to turn the director’s face livid,” a former supervising agent in the San Francisco field office recalled. “Lots of careers began and ended with that case. It was one of Hoover’s biggest failures, and he blamed everyone except himself.”

20

Australian-born, Harry Renton Bridges had arrived in the United States in 1920 as an immigrant seaman. Finding work on the San Francisco docks as a longshoreman, he became a militant labor organizer, led the West Coast maritime strike of 1934, was elected president of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), and, after the CIO broke off from the AFL, became its West Coast director. Unlike its East Coast counterpart, the ILWU was free of corruption. It also refused to enter into “sweetheart” agreements with the shipping companies, which, together with other large businesses, raised a huge fund whose sole purpose was to destroy Bridges and the ILWU. In this, Hoover was an enthusiastic accomplice. A special Bridges squad, operating out of the San Francisco field office, spent thousands of manhours attempting to prove that Bridges was a secret Communist and thus subject to deportation. But after compiling a 2,500-page report, and after more than a dozen inquiries, hearings, and appeals, Bridges remained in the United States, still head of the ILWU and a strong power in the CIO.

†

As if this weren’t bad enough, Bridges had also committed the one unpardonable sin: he’d publicly ridiculed the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Having been under investigation for so many years, Bridges found it easy to spot an FBI surveillance. When you check into a hotel, he told the

New Yorker

writer St. Clair McKelway, FBI agents usually try to rent an adjoining room. “So you look under the connecting door, and you listen. If you see two pairs of men’s feet moving around the room and hear no talking, except in whispers, you can be fairly certain the room is occupied by FBI men…Of course, you can often see the wiretapping apparatus—the wires and earphones and so forth—all spread on the floor of this other room, and then you don’t have any doubts at all.”

Once he spotted them, Bridges enjoyed playing little tricks on the agents. One of these involved inviting friends up: “We’d talk all sorts of silly stuff—about how we were planning, for instance, to take over the Gimbel strike so we could use the pretty Gimbel shopgirls to help me take over the New York longshoremen.” The sound of typing indicated, to Bridges, that this sensational information would soon be in the hands of J. Edgar Hoover. Or Bridges simply remained silent, until the agents decided he’d left the room; then he would follow them down the hall to the elevator and, without a word being spoken, accompany them to the lobby.

Spotting the agents in the lobby was even easier, Bridges claimed: “If I don’t happen to see any FBI men I know, I watch out for men holding newspapers in front of them in a peculiar sort of manner. They hold the paper so that it just comes to the bottom of their eyes, and their eyes are always peeping over the top of the paper.”

Nor was losing his “tails” any problem. Doubling back, he’d follow

them,

often to the local field office.

In July and August of 1941 Bridges made two trips to New York. Both times he stayed at the Edison Hotel, and on both occasions he was assigned the same room, even though on his second visit he requested less expensive accommodations. Confirming his suspicions, a peek under the connecting door revealed two pairs of feet and a bunch of wires.

This time he decided to have a little fun at the agents’ expense. Directly across Sixth Avenue from the Edison was the Piccadilly Hotel. After again losing his tails, Bridges rented a room that overlooked his own and that of the agents, then invited a number of acquaintances over for FBI-watching parties.

Knowing the FBI put great faith in “trash covers,” Bridges would tear up innocuous envelopes and stationery and drop them in the waste basket of his room at the Edison, then cross the street and with his friends watch the agents patiently reassemble them. For variety, he sometimes left paper dolls. Or,

knowing the FBI “just loves carbon paper,” he asked a stenographer at a second-hand clothing store for her most-used carbons. These, he was sure, were rushed to the FBI Lab in Washington, where technicians with smudged fingers probably spent hours trying to break their secret codes.

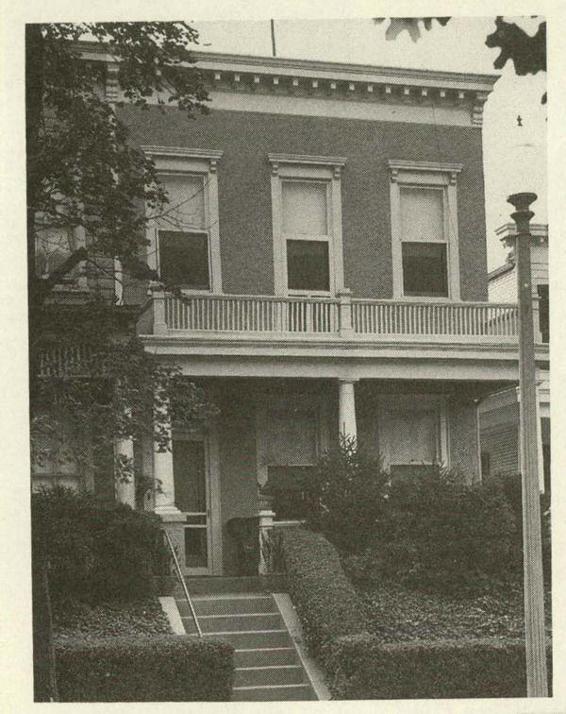

John Edgar Hoover was born on New Year’s Day 1895 at 413 Seward Square, a row house located on the edge of Capitol Hill. In the century to come, the native Washingtonian, and third-generation civil servant, would manipulate Congress in ways no president ever could.

National Archives 65-H-340.

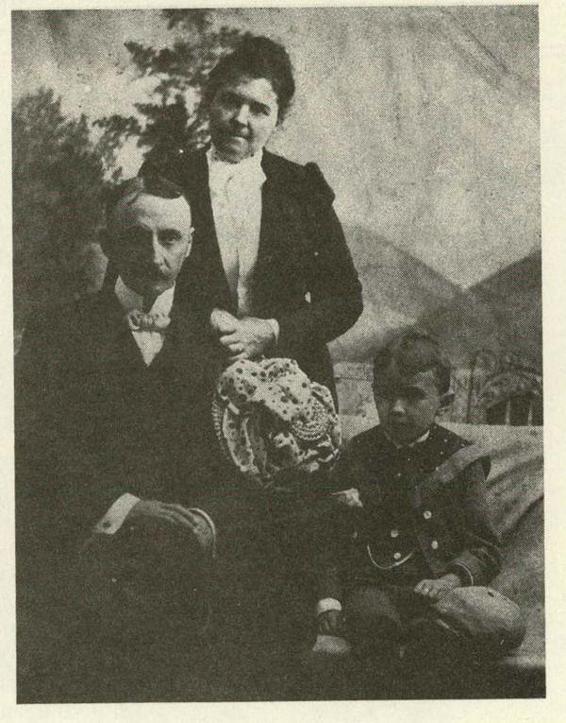

“Edgar,” or “J.E.,” with his parents. His father, Dickerson Naylor Hoover, worked for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey; his mental illness was a closely held family secret. His mother, Annie Scheitlin Hoover, was something of a martinet; she held to the old-fashioned virtues and made sure her offspring did likewise.

National Archives 65-H-297-7A.

Hoover at age four. The youngest of four children and a late bloomer, he was, according to those who knew him best, “very much a mother’s boy.”

National Archives 65-H-111-2.

Central High Cadet Captain John Edgar Hoover, probably taken about the same time he marched in President Woodrow Wilson’s 1913 inaugural parade. He would pattern the FBI after Company A, right down to its division into squads.

Federal Bureau of Investigation.

After graduating from high school, where he was elected class valedictorian, Hoover attended George Washington University. “Mother Hoover” was the unofficial house mother of her son’s college fraternity, Kappa Alpha. Hoover, who never married, lived with her until her death in 1938, at which time he was forty-three.

National Archives H-65-297-6.