Jeanne Dugas of Acadia (2 page)

Read Jeanne Dugas of Acadia Online

Authors: Cassie Deveaux Cohoon

Part 1

An Acadian

Family

Chapter 1

S

ometimes Maman grew annoyed with her when she insisted on the fact that she, Jeanne, was Acadian. Maman had said to her once, “Jeanne, you were born here in Louisbourg, and that means that you are French.”

“No,” she had replied stubbornly, “if all of you are Acadian then I am Acadian too.”

It was a question that truly vexed her and brought out her stubbornness and determination, even when she was very little. Joseph, at least, agreed with her.

“Ah well,” Joseph said, “the Acadians are known for being têtu.”

“Well,

there you are,” she had replied, stamping her foot and wondering why everyone found this so amusing.

â

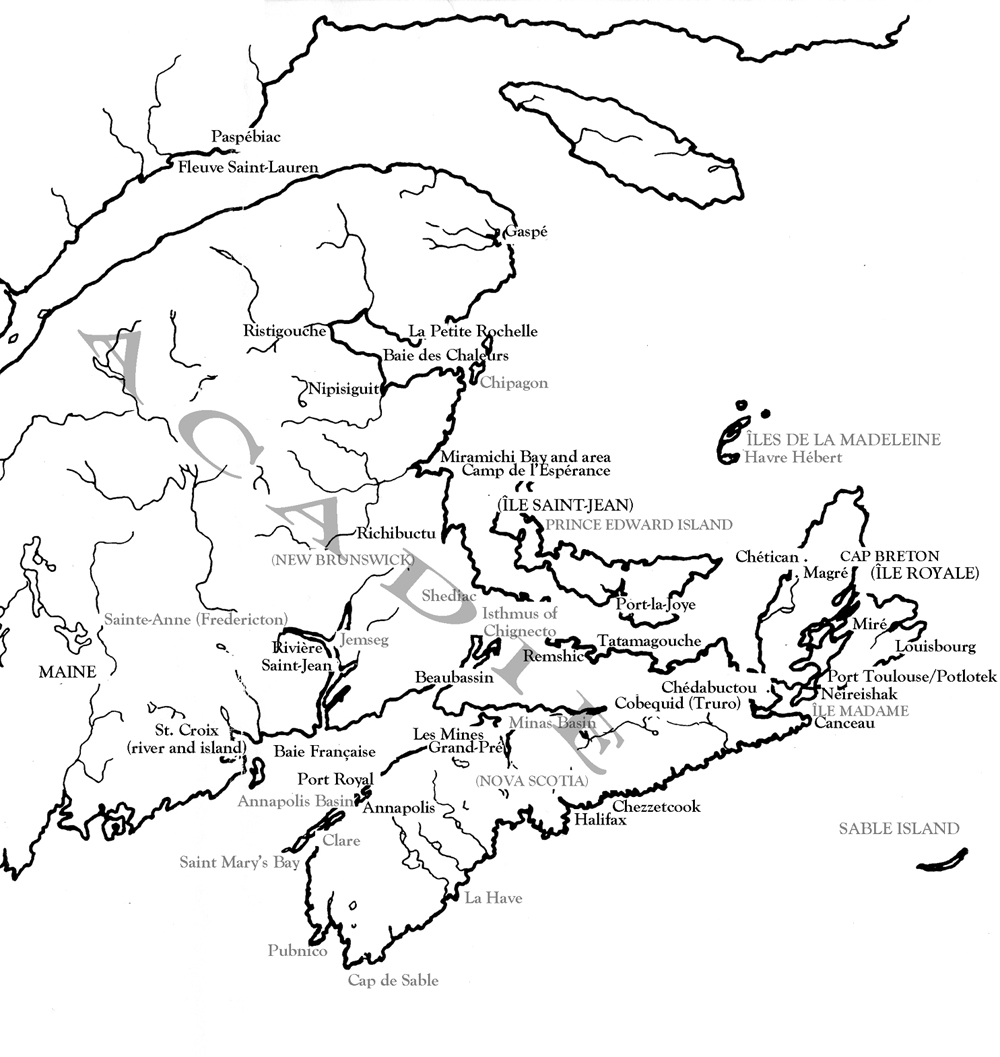

Jeanne Dugas's forebears were one of the families that founded Acadia in the first half of the 1600s. Europeans had fished the area as early as the late 1400s â Portuguese, Basques, Normans and Bretons. At first they would cross the ocean in the spring, salt their catch of fish on board ship, and return to Europe in the fall without touching land. Later, some of them set up temporary fishing outports on land for the duration of the fishing season, but they always returned to Europe in the fall. When contact was made with the Mi'kmaw people, a profitable trade in beaver fur was also developed, and European countries vigorously sought to exploit these riches.

In 1604, a certain Pierre du Gua, Sieur de Mons, set sail for that new world. The king of France had given him a grant that bestowed on him exclusive fishing and fur-trading rights over a large territory. The grant was given on the condition that he settle and cultivate the land and convert the Native people to Catholicism. The new colony was referred to as “La Cadie.” One of the men on Sieur de Mons's two ships was Samuel de Champlain, a navigator and mapmaker.

They spent their first winter on Ãle Sainte-Croix in the Baie Française, where they almost perished from scurvy and the cold. The following summer they chose a site on the rivière Dauphin, where they built a comfortable shelter. Most importantly, they became friends with the Mi'kmaq, who welcomed them and taught them how to survive in La Cadie. The Frenchmen learned how to cure scurvy by boiling the bark and leaves of evergreen trees to make a kind of tea. They learned what crops could be grown, how to hunt the animals and how to cope with the climate. They formed an alliance with the Mi'kmaq that would last for more than 150 years.

At about the same time as Acadia was growing, the British established colonies of their own, farther south along the coast, and the ancient rivalry between France and Britain on the European continent was continued in the new world. Over the next hundred years, the land of Acadia would change hands ten times between the French and the British, either through victory in war or by negotiation. For the British, to have control of Acadia was a strategic ploy. It protected their colonies along the north Atlantic coast and guaranteed the freedom of the shipping lanes for commerce. When the British were in charge, they did not bring in many settlers, at least not in the early days.

So it was really the French who settled and developed the colony of Acadia. In the 1640s, they began a system of dykes to drain the salt marshes near Port Royal and turn them into rich farmland. In the 1670s, a new community was settled in Grand-Pré in the Minas Basin area and another system of dykes put in place. Other communities followed.

When the French were in control, they had their own authorities. There was a governor, the military and of course the clergy. When the British were in control, the French elites had to leave, but the British, without a large influx of their own settlers, were dependent on the Acadians for locally grown food and meat. By and large, the two peoples accommodated each other. A system of Acadian deputies was created, whereby a delegate from each Acadian community was charged with dealing with the British governor, receiving orders and making the Acadians' needs known. The success of this system sometimes depended on the disposition of the British governor, but it worked well for some time.

By the early 1700s, Acadia had been under the control of the French since the signing of the Treaty of Bréda in 1667, and this period was a kind of golden age for the French settlers. They prospered for generations and were now their own people â Acadians.

The French settlers would originally have come from different areas of France, perhaps have spoken different dialects, have worn different styles of clothing, have had different loyalties. But over time they had become one people: Acadians, a colony of farmers who owned their own land. They were prosperous in a way they could not have been in France. And they had a certain amount of freedom, whether ruled by France or Britain.

â

Then, in 1710, the British recaptured Port Royal, and the Treaty of Utrecht, signed in 1713, handed over all of Acadia to the British; the English renamed it Nova Scotia. The French retained Cap Breton and Ãle Saint-Jean, together renamed the colony of Ãle Royale.

France also lost its fishing settlement in Placentia, Newfoundland, and proceeded to establish a fishing outport on Ãle Royale with some French fishermen and entrepreneurs from Placentia and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon. They named the new outport Louisbourg after the French king. The French authorities encouraged Acadians to emigrate to Ãle Royale.

Chapter 2

J

eanne's parents, Joseph Dugas and Marguerite Richard, were both Acadians â he born in Port Royal in 1690, she in Grand-Pré in 1694. They met in Grand-Pré and were married there in January 1711. Their first son, Charles, was born in December of the same year.

Joseph Dugas was a landowner, carpenter, caboteur or coastal navigator and trader. He was one of a new class in Acadia, owning land, but not tied to it to earn a living. With his own schooner he could move about independently. Carpentry was also a portable trade, and a respected one.

Joseph was one of the young Acadians who worried about the political situation, and his fears were confirmed when Port Royal fell to the English in the autumn of 1710. The mother country, France, had sent very little assistance to the Acadians for that battle, and Joseph was bitter but realistic. Unlike his parents' generation, he did not believe that the Acadian settlers would now continue to prosper under British rule.

Joseph's family was a prominent, close-knit one and he considered himself a man of some substance. But he had told Marguerite of his misgivings about the political situation before they married and warned her that if she joined her life to his, she must be prepared to follow him. And now, he was determined to leave Acadia, a decision not as difficult for him as for those restricted to farming.

â

In 1714, twenty-four-year-old Joseph made arrangements to leave his land in the care of relatives in Grand-Pré before setting sail on his two-masted schooner, the

Sainte-Anne

,

to resettle his family on Ãle Royale. With him were his wife and their two little sons Charles and Joseph fils, the latter

still an infant at his mother's breast. Joseph also persuaded his father, Abraham, to leave with him. The French authorities were offering a stipend to Acadian settlers to encourage them to move to Ãle Royale and Joseph Dugas accepted it, leaving his property in Acadia under the care of his brother, Abraham fils.

Their destination was Port Toulouse, on the southeast corner of Ãle Royale, on the neck of land that separated the Bras d'Or Lake from the Atlantic Ocean. An earlier French settlement, known as Saint-Pierre, had flourished there in the 17th century, but was destroyed by fire and abandoned. The area had some farmland and, although it was not as rich as that of Acadia, it had attracted some farmers. Joseph knew the area well because of his activities as a caboteur. As the fishing outport at Louisbourg grew to become the capital of Ãle Royale in the following years, Port Toulouse also grew into an important community, attracting farmers and fishermen, navigators, coastal traders, shipbuilders and loggers.

Many years later, Marguerite would confess to her daughter Jeanne that when she arrived at Port Toulouse on a cool, grey, overcast day in June of 1714, her heart sank. Living conditions were clearly not what she had been used to in Acadia â now called Nova Scotia. The few habitations were very primitive, consisting of simple vertical log construction, nothing like the solid houses they were used to in Grand-Pré. Most of them were one storey; just a few were a storey-and-a-half. Some had fenced-in yards where farm animals were kept and a few vegetables and herbs were grown. The habitations were close to the water's edge and a cold dampness penetrated both the houses and their inhabitants.

Much of Ãle Royale was rocky, with a thick forest cover. It was easy to see why most Acadians did not want to sacrifice their prosperous farms for this undeveloped land, and there were no salt marshes that could be converted to fertile farms as had been done in Acadia.

Of course there was no time for fussing. The Dugas were welcomed and sheltered by the few people already in Port Toulouse. A simple dwelling was quickly erected and they unpacked the belongings they had brought with them from Grand-Pré. Finding his young wife in tears at the end of their first week in Port Toulouse, Joseph Dugas promised her that one day he would provide her with a home she would be proud of.

â

This southwest coast of Cap Breton had once been a strategic area for the French authorities, and after 1713 they quickly sought to re-establish a settlement there, which they named Port Toulouse. It was the closest habitation to the now-British territory of Nova Scotia, making it important from a military standpoint.

The area was well known to the Mi'kmaq, who called it Potlotek. For centuries the Mi'kmaq had portaged their canoes over a narrow isthmus to the Bras d'Or Lake and used the area as a meeting place. In the summer months they made their base by the ocean on the Port Toulouse side and in the winter they camped inland on the Bras d'Or.

The French had persuaded the Mi'kmaq to adopt the Catholic religion, and they assigned a French missionary to live among them on a year-round basis. In 1713, Father Antoine Gaulin, a priest from the Séminaire de Missions Ãtrangères in Québec, established a mission for the Mi'kmaq at Malagawatch at the site of one of their traditional gathering places. The Mi'kmaq had become allies of the French against the British, and the French maintained relations with them.

â

For the energetic, ambitious Joseph Dugas, Ãle Royale was a land of opportunity. He quickly established trading contracts with the recently opened fishing outport at Louisbourg, transporting firewood and lumber there from Port Toulouse. He also carried firewood, livestock and other freight between Cap Breton and Ãle Saint-Jean, and even to and from Nova Scotia, although it was officially forbidden to trade with the British. Within two years he was no longer in need of the French stipend to help support his family and, in 1717, he acquired ownership of a considerable acreage of land in the area of Port Toulouse. A few years later, he had built himself a new schooner, the

Marie-Josèphe

. He wanted to name it the

Marguerite

after his wife, but she had refused.

By 1723, Joseph Dugas and Marguerite were well established, and their family was growing. They now had six children: Charles, Joseph and four little daughters born in Port Toulouse â Marie Madeleine, Marguerite, Anne and Angélique. Two hired hands and one servant brought the Dugas household to eleven. Sadly, Grandfather Abraham had passed away during his second winter in Port Toulouse.

By this time, thirteen Acadian families had settled there and living conditions had improved, although they were far from the comforts many had known in Acadia.

Now, Joseph Dugas was thinking of moving his family to Louisbourg, where there would be more business opportunities, and where he knew his wife Marguerite would find life more comfortable. In 1723 he was contracted to build a double house there for a blacksmith, Dominique Detcheverry. The house was on rue Royalle

,

in a good part of Louisbourg. When Detcheverry had problems paying for the construction, he agreed to give Joseph one half of the house in payment for his work. Marguerite was happy with the move; she had found the years in Port Toulouse very difficult.

â

Since 1713, the fishing outport of Louisbourg had grown very quickly. It not only exploited the rich cod fishery but had become an important trading and transhipment centre, and a strategic base in the area. By 1720, the French authorities had started a twenty-five-year fortification program to turn the outport into a fortress. It quickly became a busy, bustling community.

In the summer of 1726, Joseph Dugas sailed from Port Toulouse to Louisbourg on the

Marie-Josèphe

, with Marguerite and their family, which now included another son, Abraham, just a few weeks old. Joseph's other schooner, the

Sainte-Anne

, sailed with them, manned by others of his crew. The following year, he bought a third schooner, the

Hangoit

.

The new Dugas home was larger than the one in Port Toulouse. It was made with a heavy timber frame called charpente construction, with vertical piquet

wall fill that came from the forest near the fortress. One room was used as a carpentry workshop. The furniture was ordinary and rather worn. Although the Dugas family was not part of the elite in the Governor's circle at the garrison, Joseph Dugas was a respected craftsman and caboteur, and they had the means to live comfortably.

The Dugas had brought with them one servant and the crew from the schooners. Soon after they arrived, they acquired a black slave named Pierre Josselin. Marguerite treated him like one of the family and he responded to her kindness. He was very good with the children. Unmarried members of the ships' crews also stayed at the Dugas house when they were in port.

The Dugas family continued to prosper and grow and, in 1728, they acquired the other half of the Detcheverry house. Their eighth child, a son named Ãtienne, was born in the winter of 1729, but he died a few months before his second birthday. Jeanne, their ninth and last child, was born in the house on rue Royalle in 1731. Soon after that the busy, happy life on rue Royalle was disrupted.

â

In 1732, smallpox spread through Louisbourg. This was not so unusual, but by 1733 it reached epidemic proportions and brought with it the threat of starvation. The Dugas household was not immediately affected and Marguerite hoped and prayed that they would be spared, but late in 1732 her daughters Marie Madeleine and Marguerite died. The following winter the epidemic claimed Anne and Joseph père, as well as the slave Josselin, who was only twenty-five years old.

Marguerite had difficulty coming to terms with the death of her husband, and the loss of her three little daughters left a big void in her heart. Joseph had been the solid centre of her life â so alive, so vigorous and hard-working. Jeanne, who was barely two years old when her father died, had only one memory of this time â of her mother clutching her and her sister Angélique to her bosom as if she were afraid they too would be taken from her. Years later, when Jeanne herself had lost children, she understood her mother's anguish.

Marguerite Richard, the widow Dugas, was left with three sons, Charles, Joseph and Abraham, and two daughters, Angélique and Jeanne. But she was not destitute. As well as her home on rue Royalle, she owned two schooners, and had two domestic servants and four sailors as part of her household. There was also the land in Grand-Pré and Port Toulouse.

According to the custom of the time, male children were considered minors until the age of twenty-five. Marguerite was therefore elected to be tuteur to her three sons and François Cressonet dit Beauséjour was elected as subrogé tuteur, to assist her. He was the husband of Marguerite Dugas, a cousin of Jeanne's father. The Cressonets owned the fashionable Le Billard tavern.

Jeanne kept only a vague memory of the house on rue Royalle, because three years after her father's death, when she was only five, her mother Marguerite remarried. This event brought a big change to all their lives.