Jeanne Dugas of Acadia (5 page)

Read Jeanne Dugas of Acadia Online

Authors: Cassie Deveaux Cohoon

Chapter 9

W

ar stories circulated in the town. By the end of July, there were reports of many more British and New England privateers sailing closer to Ãle Royale, and the course of the war at sea was shifting. The arrival of privateers, with their prizes, prisoners and tales of high adventure, were eagerly awaited, but the early successes of the French privateers in June and July could not be maintained.

An exciting diversion occurred when six huge merchant ships owned by the Companie des Indes sailed into the harbour. The Companie had a monopoly over France's trade with the Far East. The ships were on their way from India back to France, and they had been told to proceed to Louisbourg because of the war. The ships brought hundreds of sailors and an air of excitement with them, distracting the people of Louis-bourg from the worries of war for a brief moment. The event was discussed at length at the de la Tour home. But the worries of war remained.

In August, British privateers and warships were seen off the coast of Ãle Royale. They disrupted the French shipping lanes and in early August five French ships were captured.

â

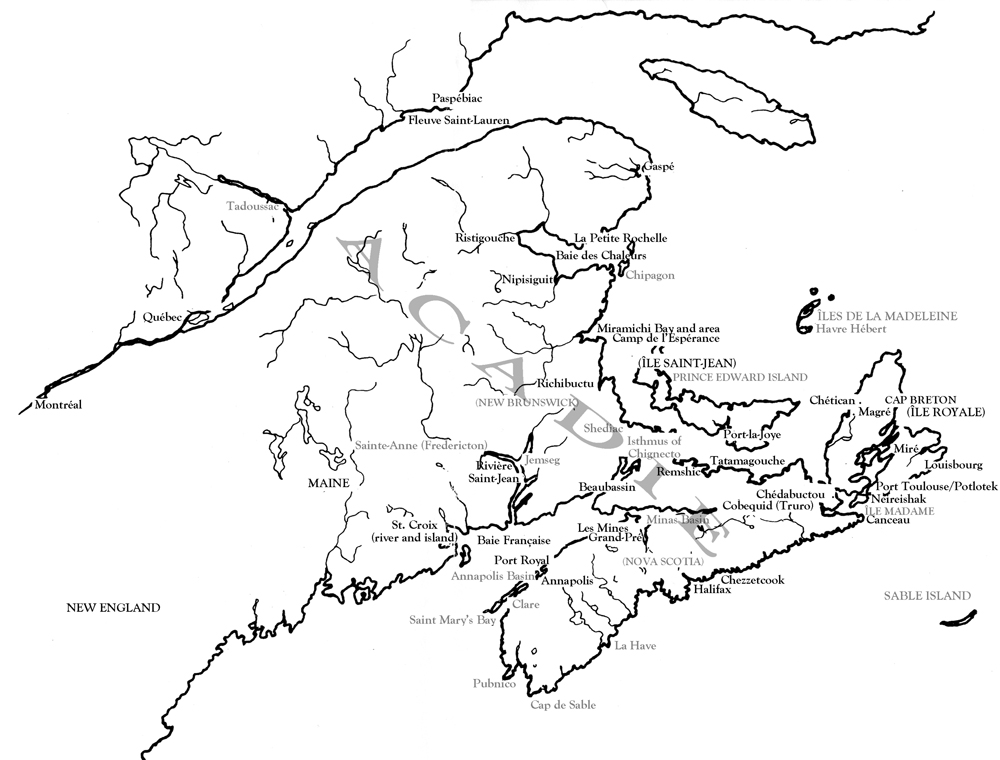

The atmosphere at the de la Tour home was becoming more sombre. Joseph visited often and his discussions with Monsieur de la Tour sometimes became heated arguments. Monsieur de la Tour wanted the family to leave Ãle Royale in the fall before winter set in, but Joseph was very reluctant to go. They also could not agree on where to take refuge. Monsieur de la Tour wanted to go to Grand-Pré where they had family and property. Joseph preferred Ãle Saint-Jean, which was more convenient for his cabotage activities and closer to Ãle Royale should the war turn in their favour.

Monsieur de la Tour accused Joseph of being a dreamer if he believed that the war would turn in their favour. In turn Joseph thought de la Tour was the dreamer, if he thought they would find a safe and permanent refuge in Grand-Pré under British rule.

“If Louisbourg falls, then we lose the French colony and that means both Ãle Royale and Ãle Saint-Jean,” Joseph said. “Do you think the British will want to keep the Acadians around then? It's only your generation that believes the Acadians can go on living here indefinitely.”

Monsieur de la Tour paused and seemed to be considering his next comments very seriously.

“Joseph, I'm as much an Acadian as you are, or Jeanne,” he said smiling at her, “but I think we are looking at simple survival here, unless we want to be deported to France when Louisbourg falls. And I think none of us wants this.”

Joseph grimaced and hung his head.

“I may be getting old,” Monsieur de la Tour continued, but we have to think of our families. We have plans to go to Grand-Pré and I believe that is our safest option now. Joseph, are you being influenced by your father-in-law? He seems to me to be a rash man. This is no time for that.”

The two men's wives exchanged a worried look. Joseph's wife said to him, “You know I love my Papa, but I trust Monsieur de la Tour's judgement in this.”

In the end, Monsieur de la Tour's views prevailed and the two families made plans to leave for Grand-Pré by the end of September. It was agreed that they would make their preparations quietly and not draw unnecessary attention to their departure.

One day Joseph found Jeanne trying to decide what to pack for their voyage, the familiar frown on her face. “Jeanne,” he asked, “what's troubling you?”

“Oh, Joseph, should I bring my blue silk gown with me? I haven't had much chance to wear it and I don't know if I'll be able to wear it over there.”

“I know,” he said, “and I'm sorry. Take it with you, but don't pack it yet. You'll be able to wear it for the feast day of Saint-Louis.”

But the feast day of Saint-Louis, on August 25, normally Louisbourg's largest public celebration, was cut back that year. The huge bonfire and military salutes were cancelled. Jeanne wore her gown, but the festivities were very subdued, especially for the de la Tours and the Dugas, whose planned departure lay heavy on their hearts.

â

The officials at the garrison were very worried. The biggest problem was a serious food shortage, caused mainly by British ships intercepting French supply vessels off their coast. Louisbourg was facing a British blockade of its port and winter was approaching.

In September, two heavily armed French warships, the

Ardent

and the

Caribou

, arrived off the coast of Ãle Royale. They drove away enemy ships, and some Louisbourg privateers and warships regained access to British waters. However,

Ardent

and

Caribou

were to return to France before winter and there was no assurance that they would come back in the spring.

A few weeks before the families left Ãle Royale, Jeanne's favourite nun, Mère Saint-Joseph, also sailed away. She had been the superior of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame since 1733. On the day of her departure, Joseph took Jeanne to the quay to say farewell to her. Jeanne told her that she would soon be leaving too and started to weep.

“Jeanne,” Mère Saint-Joseph told her, “you are strong and you must be brave too. I have faith in you and I will pray for you. Are you taking your beautiful shawl with you?”

“Yes, of course,” Jeanne smiled through her tears. “I'll keep it with me always.”

â

The de la Tour and Dugas families left for Grand-Pré in September. On the last day of November, following the worst year in the history of the cod fishery, fifty ships set sail from Louisbourg for France, leaving only a few vessels tied up in the harbour for the winter. Many men who would normally have spent the winter in the colony chose to leave with the ships because of the uncertainty over war.

Part 2

Flight to Grand-Pré

Chapter 10

A

fter the settling of accounts on the Feast of Saint-Michel, the de la Tour and Dugas families left for Grand-Pré. Monsieur de la Tour and his household sailed on his schooner, the

Cygne

. Joseph Dugas and his family sailed on his schooner, the

Marie-Josèphe

.

They brought only clothes and personal items with them. Their removal to Grand-Pré had been discussed at length on their previous trips there and they knew they would be welcomed and taken in by family. Once again they were to dress “Acadian.” Maman had allowed Jeanne, Marie and Louise to bring only one French-style gown each, and a few mementoes. Marie and Louise brought souvenirs of their life in Louisbourg, invitations and favours from social events they had attended; the twins each brought their favourite doll. Jeanne brought her blue silk gown, the necklace and her portrait, as well as her embroidered shawl. She had also sneaked most of her bibliothèque bleu books into her bundle.

They were indeed welcomed with open arms. Their older brother Charles was especially glad to see them. “You don't know the stories we hear about what's going on in Louisbourg,” he said. “And Joseph, my brother, you're here too. You're here.”

“Yes, well, I am here à contre-gré, but very happy to see you for all that, Charles. I don't know how our relatives here are going to cope with all of us.”

“Well, don't worry,” Charles said. “The only problem we've had is fighting over who will have you stay with them. And the harvest has been very good this year. It will be our joy to share it with you. Let me see your girls, Joseph.”

“Here they are,” said Joseph. “Marguerite and Anne Angélique â named for our sister.” Joseph handed his one-year-old to Charles.

“Yes. Bonjour, little Anne Angélique. You know, Joseph, I think she will look just like our Angélique.” Charles had four children himself, the last just a baby. The other three were crowded around to see the new arrivals.

The following day, Charles took the de la Tour family and Joseph to the Saint-Charles-des-Mines cemetery to visit Angélique's gravesite. Jeanne stood beside Maman, holding her hand. When Maman's prayers were interrupted by tears, Jeanne continued for her. At the end she added Maman's plea that God bless Marie Madeleine, Marguerite and Anne, and little baby Ãtienne. Maman squeezed Jeanne's hand in thanks.

Charles, who had talked to them of Angélique's last days, told Maman again how sorry he was that he had not been able to prevent her death.

“Charles, my son, I know you did all you could. We have to accept that these things are in the hands of le bon Dieu,” said Maman. “As perhaps we now have to accept that we are in His hands in our present situation.”

No one argued with her.

â

Maman, Monsieur de la Tour, Louise, Marie and the twins stayed with Charles and his family. Joseph, his family, Jeanne and young Abraham were lodged with Uncle Abraham.

Jeanne withdrew into herself at first, having to adjust not only to being away from home, but also to living with her brother Joseph and his family rather than with Maman. It's not that she objected to the arrangement â she was fond of both Joseph and his wife â but it was a kind of second separation for Jeanne. She redoubled her careful scrutiny of those around her and of her surroundings. When she realized that Monsieur de la Tour and Charles would be coming to Uncle Abraham's farm for the usual around-the-table discussions on their plight, she was grateful that she would be there. Their first serious discussion had taken place following the family's visit to Angélique's gravesite.

Uncle Abraham had in the past been one of the delegates chosen to represent the Acadians of the Grand-Pré area to the British authorities and he held very firm views on the politics of the day. He had heard of Louisbourg's successful raid against the British fort at Canceau in early summer and of the French privateers' success in capturing British ships.

Now Joseph confirmed for him that the tide had turned and that the British, helped by forces from their colonies, had inflicted losses on Louisbourg and seriously disrupted their supply routes and the activities of their privateers. “There is grave concern at the garrison that the British may be able to blockade the port next summer,” Joseph added, “unless the French government sends us some warships early in the spring.”

“What can you tell me about this man, Duvivier?” Uncle Abraham asked. “I understand he's in charge of organizing a raid on Annapolis Royal, but I'm afraid he's going to do us harm here in Acadia.”

It was Monsieur de la Tour who replied.

“I'm not proud of it, but he's one of my cousins. François du Pont Duvivier is also a great-grandson of Charles de Saint-Ãtienne de la Tour, on his mother's side. He joined the regular colonial troops when he was very young, and in his mid-twenties he was appointed an adjutant at Louisbourg, at about the same time as his uncle Louis du Pont Duchambon became Louisbourg's commander. So Duvivier has the protection of the garrison. And he has thrown himself into business, doing a lot of trading in Ãle Royale and Acadia, as well as in France and the West Indies. He has a finger in a lot of pies. And he has the protection of the two commercial officials at Louisbourg. He's made himself a fortune.” Monsieur de la Tour turned to Joseph.

“You know something about this, Joseph. When Le Normant set up a monopoly to supply fresh meat to Louisbourg, it was generally believed that while you got the contract, it was controlled by Duvivier.”

“You know very well this was never proven,” replied Joseph. “And I don't care to discuss it now.” Everyone fell silent. Jeanne was in a corner of the room, trying to remain unnoticed and take everything in. Joseph broke the silence.

“You must give Duvivier his due. He led the attack on Canceau and he brought more than one hundred prisoners back to Louisbourg.”

Uncle Abraham snorted. “Yes, and who was the young colonial lieutenant in charge of the fort who was taken as one of the prisoners?” He stared at Monsieur de la Tour.

Monsieur de la Tour shifted a little in his chair and sighed. “Another one of my cousins, John Bradstreet â Jean-Baptiste.”

“When he came to Louisbourg as a prisoner this summer, he was given preferential treatment,” Monsieur de la Tour continued. “I stayed away from him, but I did see him wandering around Louisbourg. I confess it made me feel uneasy.”

Uncle Abraham snorted again. “I don't know,” he said, “whether we should ask God to protect us from the British, or from our cousins.” There was nervous laughter around the table.

“To get back to Duvivier,” said Monsieur de la Tour. “I've heard that he is organizing a raid against Annapolis Royal. It's meant to be a follow-up to the raid on Canceau, and the start of a movement to regain Acadia. Duvivier expects to receive some ships and men from France. I understand he has recruited some Mi'kmaq and some Malecite from the rivière Saint-Jean area, and he hopes to recruit some Acadians here.

“I must admit,” Monsieur de la Tour continued, “that I'm not convinced of Duvivier's abilities. Canceau was his first military venture and it was a very easy victory. That fort was small and totally unprepared for an attack. How he will manage at Annapolis, I don't know.”

Uncle Abraham interjected. “And then this fool Joseph Leblanc dit Le Maigre, all three hundred pounds of him, was going around as an advance party before Duvivier's tour, trying to encourage people to join the raiding party. I understand he did not have much success. I'm sorry, Joseph, I realize the man is your father-in-law.”

“That's all right, Uncle. But my father-in-law is a very patriotic Acadian. Duvivier is his nephew. They only want to help the Acadian cause.”

“Heaven help us â another relation! No, Joseph, they're not going to help the Acadian cause. They're going to help the French cause. And in doing that they're going to hurt the Acadian cause.”

“What do you mean, Uncle?”

“They are not helping the Acadian cause,” his uncle shouted. “I'll give you an example. Do you remember Alexandre Bourg dit Belle-Humeur? He was a notary here in Grand-Pré and a well-respected man. He was one of the Acadian delegates reporting to the British at Annapolis Royal. Well, he lost his post this year when the British accused him of collaborating with the French through his contacts with Le Maigre and his nephew Duvivier. I doubt very much that he did collaborate, but it makes no difference.

“There's something that the French, and you apparently, do not understand. We Acadians in Nova Scotia have become our own people. We have worked hard to create a place for ourselves here and we have found a way to live peaceably with the British authorities. We have not only survived, we have prospered.

“You know that very well, Joseph, you have carried Acadian goods to Louisbourg and Ãle Saint-Jean. And we are still on good terms with the Mi'kmaq.”

“Yes, Uncle, but what about the Mi'kmaq?”

Uncle Abraham hesitated, then said, “Perhaps the most important thing we French did was to befriend the Mi'kmaq, or rather to let them befriend us. Our forefathers would have perished here without their help, and we have lived with them in peace. We farmed the lowlands; the Mi'kmaq continued to fish and to hunt in the forests. The British, I am sure, will want to take over the land completely as soon as they can bring their own people to settle here. I don't trust them.”

“Ah, Uncle, you and Monsieur de la Tour are the older generation,” Joseph said. “You don't have the mettle to do battle, do you?”

“We are the voice of experience,” Uncle Abraham replied firmly. Joseph put his arm around his uncle's shoulder, to show he did not resent his views, but it was clear that Joseph did not agree with him.

“Do you know how the Duvivier campaign is going?” Monsieur de la Tour asked Uncle Abraham.

“No. It's supposed to be still going on now. One thing we do know is that the reinforcements Duvivier was expecting from France have not yet arrived and it does not look as if they will. I don't know what it means for us if the raid is successful. Either way, there will be more fighting and hardship.”

Within a few days, there were reports that Duvivier's raid on Annapolis had indeed failed.

During the winter the British authorities interrogated the Acadian delegates in Grand-Pré about their actions during the expedition. The delegates insisted that the inhabitants of Grand-Pré had not given Duvivier any assistance except under duress. When asked about cattle conveyed to Louisbourg, the delegates replied that two droves of black cattle and sheep from Minas had been herded by Joseph Leblanc dit Le Maigre and Joseph Dugas. There were no immediate repercussions, but the people of Grand-Pré knew that this would not help their relations with the British authorities.

â

There was nothing for the families to do but to settle into the farm life of Grand-Pré for the winter months. After that first serious discussion, when Uncle Abraham made his views so clear, the men of the family met at least every other day. Joseph was not always there. He continued his cabotage activities as late into the fall as he could. And he brought back news, several times from Louisbourg itself. He managed to sail there at least twice before the sailing season ended. Sometimes he had news from other sea captains, sometimes from the Mi'kmaq. Joseph knew the three Mi'kmaw scouts, Jean Sauvage, Denis Michaud and François Muize, hired by the French to advise on the movements of British ships and their military. He kept in close contact with them.

It was Joseph's wife, Marguerite, who told Jeanne that Joseph had also been gathering military information for the French. She worried about her husband's safety.

“At least,” she said, “I thank God that he did not get it into his head to become a privateer. I worry about my father too,” she added, “but I know he's not going to change.”

Not for the first time, Jeanne wondered how such a big, rough, rowdy man like Le Maigre could have such a gentle daughter as Marguerite.