Kaboom (42 page)

Authors: Matthew Gallagher

“Well,” I started, “first I'd like to thank the army for commissioning me the day before graduation. Considering my philosophy grade still hasn't been posted, big ups to the Green Machine for showing faith in defiance of all things logical.”

Laughs. I let out another deep breath. I sought comfort through humor, and once again, I found it. The rest was easy. I thanked my family, my friends, and a litany of ROTC people who had spent hours on end showing me the practical essentials of army life. Then, spurred on by the seriousness of the words I had just sworn to live by and the pure sense of pride I felt for uttering them, I hit the esoteric ramble button of my being.

“You know, I'm here, as a lot of us are”âI pointed to my fellow commissioneesâ“because of 9/11.” Sleeping through it didn't change the fact that it had profoundly affected me. “But that doesn't really matter now. We have a job to do, and we're going to do it. The whys will stay here in academia, as they should, I think. I'm as surprised as a lot of you are that I ended up going the route I've chosen. But I couldn't be more proud or more excited. It's going to be a hell of a ride, that much I know. Catch you on the flip side, and keep it real.”

My brother, who sat in the audience next to my girlfriend, later told me I had spent my entire portion of the ceremony looking like I'd been punched in the gut but still managed to smirk during the whole thing. “Quite the feat,” he told me. He also said I didn't really smile until I sat back down, when the spotlight shifted to the next new lieutenant. I guess I always hated dog and pony shows, even before I knew what the term meant.

A few years later, when I left for Iraq, I took that same pair of Guinness socks with me. On days I wanted to remember who I had been and who I was and who I still wanted to be, I wore them on patrol, underneath my dirty, dust-covered tan combat boots. They still felt as smooth as a hawk's glide.

HOW TO JOINT-PATROL“Dude, where'd your moustache go?”

Lieutenant Dirty Jerz asked me. “It was finally starting to fill in.”

Lieutenant Dirty Jerz asked me. “It was finally starting to fill in.”

While JSS Istalquaal still hadn't evolved into a salute zone since our battalion's move there, certain outpost liberties had already been snuffed out. Like moustaches. Originally concocted by the few armor officers on the JSS as a tribute to our cavalry forbearers for morale purposes, the practice of growing a moustache had spread to the other branches and to some of the NCOs and soldiers as a show of company-level solidarity. The field grades frowned upon the so-called Ride of the Moustachioed and thus ordered our

ringleader, The Hammer, to destroy any and all signs of officer upper-lip hair. Turned out, the only thing infantrymen hated more than hippies and techno music was moustaches. And so, my valiant attempt at a handlebar ended, quite prematurely. Considering that with it I resembled a child molester more than I did one of Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, the order couldn't have come a moment sooner.

ringleader, The Hammer, to destroy any and all signs of officer upper-lip hair. Turned out, the only thing infantrymen hated more than hippies and techno music was moustaches. And so, my valiant attempt at a handlebar ended, quite prematurely. Considering that with it I resembled a child molester more than I did one of Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, the order couldn't have come a moment sooner.

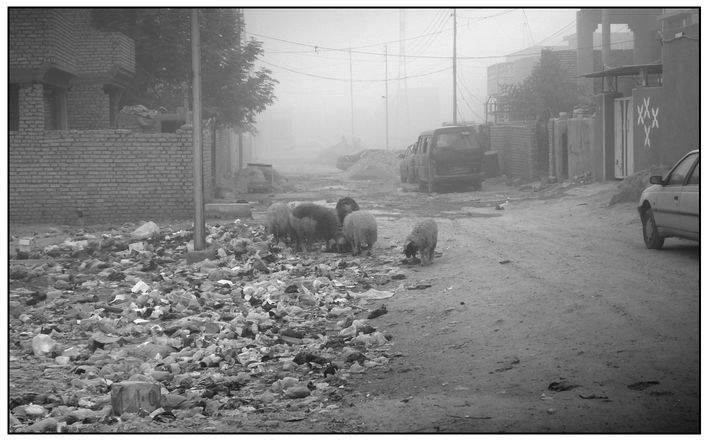

A heavy orange sandstorm did not stop our dismounted patrol through Hussaniyah in the autumn of 2008, nor did it stop these sheep from eating trash.

“It was my sacrifice to the new gods of Istalquaal,” I said smugly, “last seen at the altar of the porcelain sink.”

Lieutenant Dirty Jerz and I walked up the slight, half-mile incline that separated the company TOCs from the new battalion headquarters on JSS Istalquaal. A chilly, early December wind swirled through the late-morning air, something not lost on the flapping American flag displayed prominently on a pole next to battalion. I needed to drop off some paperwork with the battalion intelligence gurus, while he needed to talk to the Iraqi police dispatcher, whose office was located behind battalion.

“You want to come on patrol with us?” Lieutenant Dirty Jerz asked. “I'm coordinating for some IPs since every patrol has to be âjoint' now. We're checking out that rumored IRAM [improvised rocket-assisted mortar] factory site. You got anything better to do?”

I laughed. “Nope, just a meeting that will take what little is left of my soul. I'm definitely in. What time is your patrol brief?”

“Ten minutes before noon.”

“Word.”

A wave of IRAM threats had swept the greater Baghdad area in recent weeks, something that instilled legitimate fear in all of us, from the lowest-ranking private to all of the generals at Camp Victory and Camp Liberty. Designed for catastrophic attacks, the IRAM seemed tailor made for assaults on urban combat outposts; in essence, it lobbed multiple bombs, rockets, mortars, or ball bearings over obstacles like fences and T-wall barriers in an arced trajectory. The difficulties of defending against the IRAM compounded its dangers, as an attack could be initiated from the bed of a small truck by remote control. The device sort of reminded me of a Transformer, from the 1980s cartoon show, but I didn't want to sound any more juvenile or irreverent than I already came across, so I kept that thought to myself. While this threat was nothing new to the Iraq War, an IRAM attack on JSS Ur directly to our south in July 2008 had, according to the after-action reports, barely avoided becoming an outright disaster for Coalition forces. While JSS Istalquaal didn't seem like a prime site for an IRAM attack, as opposed to places like JSS Ur, located in the heart of that city, and Saba al-Bor, a smattering of intelligence reports suggesting that IRAM construction was transpiring in Hussaniyah became a focus of our brigade's leadership. Thus, it became our new daily patrol focus as well.

Although not necessarily stoked to be IRAM hunting, I knew I needed to get back out of the wire, so I felt thankful Lieutenant Dirty Jerz had asked me to come along. With battalion on the JSS, my PowerPoint output had increased exponentially, and a self-respecting man could handle only so much of that. After I dropped off the aforementioned paperwork, I walked back to the Iraqi police dispatch office to thank Lieutenant Dirty Jerz properly for the patrol invitation. I found him talking to the dispatcher through an interpreter.

“I understand this patrol isn't on your schedule,” Lieutenant Dirty Jerz said through clenched teeth, “but it's important. We had a new intel report come in, so we have to adjust. We're leaving in an hour. You're telling me you can't get me a few guys in an hour? All I need is two guys.”

The Iraqi dispatcher jolted visibly, rattled off a sentence in Arabic into his handheld radio, and waited for the reply. The interpreter heard it and turned to Lieutenant Dirty Jerz.

“His captain say that they have no one available because patrol not on schedule. Sorry, he say, but captain say it should have been on schedule.”

Lieutenant Dirty Jerz laughed bitterly. “Of course!” he said. “I'll keep that in mind. Tell the dispatcher it's okay. I don't blame him.”

I walked up to him and slapped him on the back. “The IPs being their normal, efficient selves?” I asked.

“Jesus Christ,” he said, “same old story, different day. They won't let me out of the gate if I don't have any Iraqis with us, but there's not an IP to be found right now.”

“Perception versus reality. It can be a mother fucker. We got to raise that joint-patrol number tally, though. That's what is really important here.”

“No shit,” he fumed. I doubted I'd ever seen him this aggravated. “I mean, I understand the purpose behind the joint-patrol concept, and when it works the way it's supposed to, it works greatâwhen I can sit down and plan with their lieutenant or squad leader, and we get more than two of them to throw in the back of our Strykers. But it almost never works like that. This is Iraq, not training. It's just turned into another check-the-block exercise.”

“Maybe try and get some National Police?” I offered. “They're usually better with adjusting to the mission.”

“Yeah, that's my next stop.”

At ten minutes to noon, I stood in the motor pool in full battle rattle, next to the platoon's four Strykers, surrounded by forty or so of Lieutenant Dirty Jerz's soldiers and NCOs. Lieutenant Dirty Jerz stood on the back of a lowered Stryker ramp, ready to give his patrol briefâas we all waited for the two junior NCOs who had been sent to retrieve the four Iraqi National Police already coordinated for. We continued to wait for twenty minutes, idle chatter filling the silence. Ten minutes after noon, Captain Frowny-Face's voice came over the radio.

“Blue 6, this is Gunslinger 6. Why haven't you departed yet?”

“Those fucks,” Lieutenant Dirty Jerz said to no one in particular. “Major Husayn assured me they'd be ready on time.”

SFC A spoke up. “Sir, you better go talk to the commander. I'll go find the bastards and get 'em down here.”

While we waited, I sat down next to Barry, the platoon's baby-faced interpreter. “Why are they late, Barry?” I asked kiddingly. It had become a companywide joke to blame FUBAR matters on this young terp, as a sort of hazing ritual. The young Iraqi usually played along, using self-effacing humor as a defense mechanism.

This time, though, Barry did not share in or understand the taunt and instead responded all too literally. “Because they are Iraqi,” he said. “We Iraqis do not like schedule. Americans are crazy with schedule. This will never change.”

Fair enough, I thought. A more honest answer than I anticipated, but I probably deserved it for attempting to joke with the kid.

Five minutes later, seven bodies crested the top of the motor pool, all running. We could all hear SFC A yelling, “Faster, you bastards. Move faster!” as they moved, causing all of us to break out in hysterics. SFC A, the two junior NCOs, and four very winded Iraqi National Police broke into our circle, ready for the patrol brief.

“Sorry we're late, sir,” SFC A said to his platoon leader. “The NPs were giving our guys the runaround up there. They just needed a swift kick in the ass.”

“I'm sure you were able to take care of that,” Lieutenant Dirty Jerz said, grinning widely. He then gave his patrol brief, while Barry translated the specifics to the four NPs. They said they understood what we sought and what they needed to do when we dismounted.

The IRAM-factory report turned out to be a dry hole; we found nothing but a long-abandoned concrete factory. The National Police performed satisfactorily on the ground with us, as they usually did. And one more joint-patrol got tallied for the great PowerPoint slide in the sky.

MERRY FUCKING FRAGO“I have celebrated

some really bizarre holidays during my time in the army,” SFC Hammerhead said from the driver's seat of the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) armored vehicle, which is designed specifically to survive IED attacks. “But this might fucking take the cake.”

some really bizarre holidays during my time in the army,” SFC Hammerhead said from the driver's seat of the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) armored vehicle, which is designed specifically to survive IED attacks. “But this might fucking take the cake.”

Exactly one year after I spent Christmas Eve with the Gravediggers in Kuwait, I trolled through the streets of central Baghdad with the Gunslingers Company, hunting for VBIEDs and car bombs. This seemed like normal Iraq counterinsurgency activity until we remembered we were conducting this mission set in the Green Zone, purportedly the safest part of Iraq and home to a multitude of government palaces, villas, headquarters, and international embassies. Iraqi security forces were slated to take control of the Green Zone

on January 1, but a rash of car-bomb threats on the area threatened that benchmark date. Thus, in an effort to beef up security until then, division shifted units down to Baghdad a company at a time. Our slot just happened to fall from December 24 to December 26âsomething relayed to us on the evening of December 23. After all, nothing said Merry Fucking Christmas like a big, whopping plate of frago. Now, having spent over a year in combat, most of us were too tired to care, let alone fight it.

on January 1, but a rash of car-bomb threats on the area threatened that benchmark date. Thus, in an effort to beef up security until then, division shifted units down to Baghdad a company at a time. Our slot just happened to fall from December 24 to December 26âsomething relayed to us on the evening of December 23. After all, nothing said Merry Fucking Christmas like a big, whopping plate of frago. Now, having spent over a year in combat, most of us were too tired to care, let alone fight it.

Statues of Saddam Hussein, discovered in a parking lot on a large forward operating base in the Baghdad Green Zone.

Back in our present, the MRAP's gunner, Sergeant J, yelled from above, “Did SFC Hammerhead say something about cake?” he asked, kicking his legs at the same time. “I want cake! I'm starving!”

Other books

a Touch of the Past (An Everly Gray Adventure) by Charles, L. j.

Die for You by Lisa Unger

Roman Blood by Steven Saylor

Sleeping Beauties by Susanna Moore

The Shopkeeper by James D. Best

El mundo perdido by Michael Crichton

Rose of the Mists by Parker, Laura

Wish Upon a Star by Klasky, Mindy

Run Girl: Ingrid Skyberg FBI Thrillers Prequel Novella by Eva Hudson

Spirit of the Revolution by Peterson, Debbie