Kennedy: The Classic Biography (44 page)

Read Kennedy: The Classic Biography Online

Authors: Ted Sorensen

Tags: #Biography, #General, #United States - Politics and government - 1961-1963, #Law, #Presidents, #Presidents & Heads of State, #John F, #History, #Presidents - United States, #20th Century, #Biography & Autobiography, #Kennedy, #Lawyers & Judges, #Legal Profession, #United States

Except for the depressed areas-West Virginia committee—which kept an old Kennedy commitment by immediately organizing for hearings in West Virginia under Senator Paul Douglas—the formation of these task forces was not announced. The close to one hundred men serving on them were drawn largely from the professions, foundations and university faculties, including two college presidents, in an unusually swift mobilization of the nation’s intellectual talent. The names of those of the thirteen for which I was responsible were drawn from the personal files, friendships and memories of various members of the Kennedy team and from recommendations by the chairman of each group.

1

Partly because it was a time of intellectual hope and cooperation with the new administration, and partly because it was a time when talent was being recognized in prestigious appointments, no one, to my recollection, refused a request to serve on a task force. In some cases their acceptance did sound a little less eager than their initial response to the operator’s statement, that “Mr. Sorensen is calling from Palm Beach.”

The members of these task forces received no compensation and usually no expense money. In many cases only the chairman received public credit and a personal visit with the President-elect. Many of these specialists were sooner or later offered positions in the administration—men such as Jerome Wiesner, Walter Heller, Wilbur Cohen, Mortimer Caplin, Henry Fowler, James Tobin, Stanley Surrey, Adolf Berle, Joe McMurray, Tom Finletter, Robert Schaetzel, Donald Hornig, Frank Keppel, Lincoln Gordon, Jerry Spingarn, Champion Ward, Arturo Morales Carrion and many others, including those previously mentioned in our list of “academic advisers.” But some were not asked and some were unable to accept. Moreover, fiscal limitations, legislative opposition or other practical inhibitions often reduced the implementation of their work so sharply as to cause them disappointment if not dismay.

The President-elect’s private judgment on the task force reports, as they were delivered in early January, ranged from “helpful” to “terrific.”

2

Some, such as the Symington report calling for a wholesale reorganization of the military services along functional lines, were too controversial to be more than a stimulant to future planning. Others, such as the nine-billion-dollar program urged by Purdue’s President Frederick Hovde and his blue-ribbon task force on education, set a standard which could not immediately be reached. But all provided useful facts, arguments and ideas, and nearly all were directly reflected in legislation. Paul Samuelson’s antirecession task force, for example, had a major role in shaping the new administration’s early economic proposals (and also redoubled Kennedy’s futile efforts to induce Samuelson to leave the academic calm that he relished and join the “New Frontier”).

But composition of the new President’s program neither awaited nor depended upon completion of the task force reports. In November and December, with the help of the Budget Bureau staff and my associates, a master check list of all possible legislative, budgetary and administrative issues for Presidential action was prepared.

3

This list was then refined and reduced to manageable proportions in a conference with our new Budget Director and his hold-over Deputy Director; and on December 21 a list of over 250 items, ranging from area redevelopment to Nike-Zeus, was reviewed in a rugged all-day and late-night session with the President-elect in Palm Beach. “Now I know,” he said, looking over the length and complexity of the list, “why Ike had Sherman Adams.”

He was well rested by then. His mind was far more keen and clear than it had seemed when I had last visited Palm Beach two weeks after the election. He had still seemed tired then and reluctant to face up to the details of personnel and program selection. Now he was deeply tanned, and as he changed from his swimming trunks in his bedroom, he joked about how fat he looked. His comments were precise and decisive, and it was a tonic to me to see that he could hardly wait until the full responsibility was really his.

When we interrupted our session for lunch, he told us with a touch of humor about the assassination attempt uncovered the week before. A deranged New Hampshire resident had driven his car to Florida, filled it with dynamite and planned to crash it into Kennedy’s. When finally picked up on December 15 by the Secret Service tracing a tip from his home town, he said that he had foregone a perfect opportunity the previous Sunday only because Jacqueline and the children were also present. The President-elect seemed more intrigued than appalled by the man’s ingenuity in planning a motiveless murder, and then he dismissed it from his mind and returned to work.

On some items he asked questions of his new Budget experts who were present; on some he requested memoranda of additional detail or arguments from his Cabinet appointees who were not. Some matters he postponed as of lower priority or doubtful desirability. Some he referred to his task forces for recommendation. A few he preferred to delete altogether. He also added a few items on his own: a commission on campaign costs, a memo to all appointees to hold down Federal employment and another to divest themselves of all conflicts of interest.

It has since been widely reported that Kennedy, alarmed by the narrowness of his winning margin, had decided to retreat from his original plans for his first year. Certainly no alarm or retreat was sounded in this meeting. The President-elect was aware of the legislative realities. He exercised caution consistent with his new responsibilities. And he did not feel free, with the dollar appearing slightly shaky, to reverse in one month the fiscal philosophy that he felt had weakened the economy for years. But reviewing my notes on that December 21 check list, I see no signs of a slowdown. Not a single one of his major campaign pledges was ignored or interred.

On the basis of that December 21 conference, a detailed letter of questions and requests was sent to each prospective member of the Cabinet, assignments were meted out for the drafting of detailed proposals and documents, new budget estimates were prepared, the task force reports were fitted in—and a Kennedy Presidential program took definite shape well before Kennedy became President. The amount of preparation was unprecedented. Clearly it made it possible for the new President to take the legislative initiative immediately. In almost every critical area of public policy—including recovery from the recession, economic growth, the budget, balance of payments, health care, housing, highways, education, taxation, conservation, agriculture, regulatory agencies, foreign aid, Latin America, defense and conflicts of interest—comprehensive Presidential messages and some 277 separate requests would be sent to the Congress in Kennedy’s first hundred days.

Kennedy was irritated, however, by widespread press speculation that he intended to emulate the first hundred days of Franklin Roosevelt, who had taken office with a landslide vote, in the midst of a depression and with heavy Congressional majorities, and consequently rushed through far-reaching legislation almost immediately. Kennedy had emphasized the necessity of “setting forth the

agenda”

in the first hundred days, but had no illusions that the Congress and country of 1961 bore any resemblance to 1933.

INAUGURATION

Early in January, with work on his program well under way and his principal nominees named, the President-elect’s thoughts turned more and more to his inauguration. He took a lively interest in plans for the Inaugural Concert and five simultaneous Inaugural Balls (all of which he would attend), in plans for the four-hour-long Inaugural Parade (all of which he would watch in twenty-degree temperature), the million-dollar Democratic fund-raising Inaugural Gala (which he greatly enjoyed, despite a two-hour delay due to blizzards) and in all the other festivities. He asked Robert Frost to deliver a poem at the inauguration ceremony. He wanted Marian Anderson to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” He sought a family Bible on which he could take the oath of office without arousing the POAU. He indicated that top hats instead of Homburgs would be in order for the official party. And, finally and most importantly, he began to work on his Inaugural Address.

He had first mentioned it to me in November. He wanted suggestions from everyone. He wanted it short. He wanted it focused on foreign policy. He did not want it to sound partisan, pessimistic or critical of his predecessor. He wanted neither the customary cold war rhetoric about the Communist menace nor any weasel words that Khrushchev might misinterpret. And he wanted it to set a tone for the era about to begin.

He asked me to read all the past Inaugural Addresses (which I discovered to be a largely undistinguished lot, with some of the best eloquence emanating from some of our worst Presidents). He asked me to study the secret of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (my conclusion, which his Inaugural applied, was that Lincoln never used a two- or three-syllable word where a one-syllable word would do, and never used two or three words where one word would do).

Actual drafting did not get under way until the week before it was due. As had been true of his acceptance speech at Los Angeles, pages, paragraphs and complete drafts had poured in, solicited from Kraft, Galbraith, Stevenson, Bowles and others, unsolicited from newsmen, friends and total strangers. From Billy Graham he obtained a list of possible Biblical quotations, and I secured a similar list from the director of Washington’s Jewish Community Council, Isaac Franck.

The final text included several phrases, sentences and themes suggested by these sources, as did his address to the Massachusetts legislature. He was, in fact, concerned that the Massachusetts speech had pre-empted some of his best material and had set a mark that would be hard to top. Credit should also go to other Kennedy advisers who reviewed the early drafts and offered suggestions or encouragement.

But however numerous the assistant artisans, the principal architect of the Inaugural Address was John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Many of its most memorable passages can be traced to earlier Kennedy speeches and writings. For example:

| Inaugural Address | Other Addresses |

| For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. | … man…has taken into his mortal hands the power to exterminate the entire species some seven times over. |

| | — Acceptance speech at Los Angeles |

| … the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans…. | It is time, in short, for a new generation of Americans. |

| | — Acceptance speech and several campaign speeches |

| And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country. | We do not campaign stressing what our country is going to do for us as a people. We stress what we can do for the country, all of us. |

| | — Televised campaign address from Washington, September 20, 1960 |

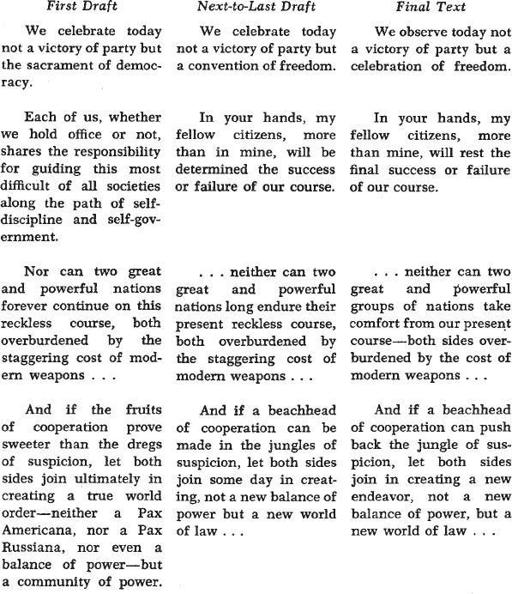

No Kennedy speech ever underwent so many drafts. Each paragraph was reworded, reworked and reduced. The following table illustrates the attention paid to detailed changes:

Initially, while he worked on his thoughts at Palm Beach, I worked at my home in a Washington suburb with telephoned instructions from the President-elect and the material collected from other sources. Then I flew down, was driven to his father’s oceanside home, and gave him my notes for the actual drafting and assembling. We worked through the morning seated on the patio overlooking the Atlantic.

He was dissatisfied with each attempt to outline domestic goals. It sounded partisan, he said, divisive, too much like the campaign. Finally he said, “Let’s drop out the domestic stuff altogether. It’s too long anyway.” He wanted it to be the shortest in the twentieth century, he said. “It’s more effective that way and I don’t want people to think I’m a windbag.” He couldn’t beat FDR’s abbreviated wartime remarks in 1944, I said—and he settled for the shortest (less than nineteen hundred words) since 1905.

“I’m sick of reading how we’re planning another ‘hundred days’ of miracles,” he said, “and I’d like to know who on the staff is talking that up. Let’s put in that this won’t all be finished in a hundred days or a thousand.”