Kierkegaard (16 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

The

Corsair

was one of the founding members of the Kierkegaard fan club. It had praised Søren by name in 1841.

Either/Or

got a favourable nod in 1843. In May 1845 it made positive noises about the pseudonymous books, alluding to Kierkegaard as the author. Later that year Hilarius Bookbinder was lauded, and the November 14, 1845, edition immortalised Victor Eremita, claiming that in the annals of literature, his name “

will never die

.” That piece of puffery prompted Søren to draft a response in the guise of Victor, asking the

Corsair

to slay him as it slays everyone else. “

To become immortal

” through the

Corsair

, Victor claims, “will become the death of me.” In the end Søren decided to leave this letter in the drawer. However, he would repeat the same sentiment in public the following year.

From his conversations with Aron and his journals it is evident that there is justice in Søren's claim that his stand against the

Corsair

had

been brewing for some time. It was, however, a poison piece from Møller that catalysed the fight. For his part, Møller had been prompted by Kierkegaard's pointed insinuations to Goldschmidt when he distinguished between the author of

A Jew

and the driving force behind the

Corsair

. Møller did not share his friend's fair-minded approach to Søren's foibles, and he seems determined to take the ironist down a peg or two before Søren could do the same to him.

Caricature of Søren by Wilhelm Marstrand about 1870. Even after his death in 1855, Søren was dogged by unflattering portraitsâwith their curved spines and ill-fitting trousers.

As part of his bid for academic credibility, Møller had started a literary journal of his own called

Gæa

. In the December 22, 1845, edition, Møller published a long review, ostensibly of

Stages on Life's Way

. It was deliberately structured so as to give the impression the piece represented the views of a number of luminaries from the academy. The review soon expands to take in

Either/Or

,

Fear and Trembling

,

Prefaces

, and other works by Søren, including his letters to newspapers. Significantly, despite alluding to various authors, the only name that prominently appears in the piece is that of “S. Kierkegaard.” There are occasional cold words of praise but overall the tone is snide and contemptuous. Møller also steers his review into deeply personal territory, seeing Søren's relations with Regine in the worst possible light:

But to spin

another creature into your spider web, dissect it alive or torture the soul out of it drop by drop by means of experimentationâthat is not allowed, except with insects, and is there not something horrible and revolting to the healthy human mind even in this idea?

Søren's sexual life (or lack of same) is crudely alluded to more than once: “

He satiates himself

by writing; instead of reproducing himself with a foetus a year as an ordinary human being he seems to have a fish nature and spawns.” Charming.

Cartoon from the

Corsair

. Søren stands alone while the universe revolves around him.

Søren was not one to let personal slights and bad reviews pass unnoticed, but the majority of his responses remained in draft form in his writing desk. This would not be one of those times. Søren's response was swift and decisive. On December 27, 1845, the

Fatherland

contained a rejoinder from Frater Taciturnus. The lengthy article comes out swinging and lands many blows against P. L. Møller. Søren too was adept at wielding rumours, and he paints an unflattering picture of a Møller who is willing to do anything for money and whose

Gæa

article falsely insinuates the author into a company of academics with whom he has no business being associated. Regarding

Gæa

's interpretation of Søren's authorship, Søren openly questions Møller's basic ability to understand what he is reading: a low blow against a man with pretensions to a professorship in aesthetics. The knockout punch comes at the end of the article. Near the finish of the essay, which until now had been all about Møller and the discussion of

Stages In Life's Way

in

Gæa

, the good Frater Taciturnus concludes:

Cartoon from the

Corsair

. A grateful member of the public receives the latest offering from Master Kierkegaard.

Would that I

might only get into the

Corsair

soon. . . . My superior Hilarius Bookbinder, has been flattered in the

Corsair

, if I am not mistaken. Victor Emerita has even had to experience the disgrace of being immortalizedâin the

Corsair

! And yet, I have already been there, for

ubis spiritus, ibi ecclesia: ubi

P. L. Møller,

ibi

the

Corsair.

“

Where the Spirit is

, there is the Church: Where P. L. Møller is, there is the

Corsair.

” With these words, Søren launched his attack on

the paper and its “loathsome” assaults “on peaceable, respectable men.” He did so without drawing Goldschmidt into the fray, and by directly naming and shaming Møller instead. It was a swift jab at the ambitious author's weakest spot, and he meant it to sting.

Møller's involvement with the

Corsair

was an openâyet unspokenâsecret. Thus Kierkegaard's phrase was not a revelation so much as it was an intentional trumpet blast where silence usually reigned. Kierkegaard's breach of the etiquette surrounding pseudonymity had its desired effect. The public eye latched on to Møller. Even before the literary spat he was a controversial outsider to the professorship position he most coveted. Møller wrote an insincere conciliatory letter to the

Fatherland

a couple of days later, but the damage was done. It is unlikely that he would have got the post in any case, but as the events transpired, Møller perceived that his calling-out in the

Fatherland

was the decisive factor. Aron Goldschmidt agreed, writing years later: “

Kierkegaard pounced

on him with such vehemence, used such peculiar words, had, or seemed to have, such an effect on the public that the professorship, instead of being brought closer by

Gæa

, was placed at an immeasurable distance.”

Cartoon from the

Corsair

. A startled Kierkegaard is confronted on the street by the meek and mild

Corsair

, cap in hand.

With nothing left to lose, the

Corsair

struck back. The January 2, 1846, edition contains a satirical conversation between the editor of the

Fatherland

and Frater Taciturnus, who plot the downfall of the

Corsair

and heap praise on “

Denmark's greatest mind

, the author of Denmark's thickest books.” Kierkegaard is named in person in the following issue, where a mocking conversation between Søren and other public figures

of Copenhagen soon devolves into a discussion of Søren's tailor, with the joke that Kierkegaard arranges his trouser legs to be uneven “

in order

to look like a genius.” The trouser talk continues, accompanied by pictures from cartoonist Peter Klæstrup. Søren's second and final reply to the

Corsair

appeared in the

Fatherland

on January 10, where Frater Taciturnus names Goldschmidt as an editor and likens the

Corsair

to a streetwalker one must pass by, and as a mercenary paper that attacks people for profit. The allusion brings to mind Møller's infamous dalli

ances with prostitutes on the one hand, and Aron would later interpret the “mercenary” jab as an allusion to his Jewishness on the other. Whether or not these were indeed Kierkegaard's intentions, in any case his letter ends with a renewed plea, “

May I ask

to be abusedâthe personal injury of being immortalised by the

Corsair

is just too much.”

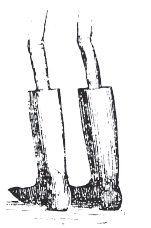

Cartoon from the

Corsair

. The notorious legs get another outing.

Søren stayed silent (at least in public print), but Møller and Goldschmidt continued their onslaught. For the next six months the

Corsair

would keep up the running joke, with most editions containing multiple caricatures and “comic compositions” at Kierkegaard's expense. The pieces share a common quality in that they trade in mocking Søren's awkward physical characteristics and questioning his sanity. Søren is intentionally mistaken for a local eccentric known as “Crazy Nathanson,” and the idea that his clothing (especially the trousers) are ill-fitting is driven home in drawing after drawing. It is the cartoons, and not the prose, that stand out the most from the whole affair. The attempts at humorous writing rarely hit their marks, but Klæstrup's caricatures are brutal in their ability to take something true about their target and use it against him. One shows Søren's ungainly attempts to ride a horse, another portrays a lumpen

Søren cowering in the doorway of the

Corsair

's offices. Another has Søren riding about on the back of a young girl. More pictures show Søren on a pedestal, presenting yet another of his books to a bowing and scraping member of the grateful public. One simply shows a humpbacked figure in silhouette, surrounded by the flotsam and jetsam of Copenhagen life, placing Søren, alone, in his own private universe.