Kierkegaard (18 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

It did not take Søren long to realise that his idea of concluding the authorship and taking up a quiet residency as the pastor in a village church was not going to fly. By January 20, 1847, he could write how “the wish to be a rural pastor has always appealed to me and been at the back of my mind. . . . It seems perfectly clear, however, that the situation here at home is becoming more and more confused.” He perceives the times demand an extraordinary figure and dares to think this might be him. “

When I gave

[Regine] up, I gave up every desire for a cosy, pleasant life,” he writes, but “from now on I must take being an author to be the same as being at the mercy of insult and ridicule. But to continue along this road is not something self-inflicted, for it was my calling; my whole habitus was designed for this.” In this same entry, Søren finds connections between Mynster's “idolization of the establishment,” “bourgeois mentality,” the “cowardice and envy” of the cultured elite, and the violence of the “rabble-barbarians.” The course Søren was setting was nothing less than a collision with all of Christendom.

Humanly speaking

, from now on I must be said not only to be running aimlessly before me but going headlong toward certain ruinâtrusting in God, precisely this is the victory. This is how I understood life when I was ten years old, therefore the prodigious polemic in my soul; this is how I understood it when I was

twenty-five years old; so, too, now when I am thirty-four. This is why Poul Møller called me the most thoroughly polemical of men.

The fight to save Goldschmidt's soul and that of the common man from the

Corsair

was not going be an extra project added on to a concluded writing career. Instead, for Søren, the affair and its fallout marked a new turn in the path Governance had set him on years before. The monstrous public had loomed up, and Søren began to think he was the man appointed to slay it.

But to do that he would need to write more books.

An Armed and Neutral Life

It is 1838. The old father has just passed away. The youngest son takes it upon himself to tell the family pastor the sombre news. The father had always revered Mynster and shaped his family's spiritual formation along lines Mynster set. Now, upon being informed of the old man's death, Mynster is puzzled.

Who

has died? It takes him a moment or two to recall how he knows the name of Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. The preacher is a busy man with many demands on his time and many parishioners. But the son remembers that the

bishop forgot

.

“Voluntarily exposing myself to attack by the

Corsair

is no doubt the most intensive thing along the order of genius that I have done,” Søren reflected in 1849. “It will have results in all my writing, will be extremely important for my whole task with respect to Christianity and to my elucidation of Christianity.” In this he was correct. The effects of the

Corsair

, while apparently trivial to some, were in fact deep and long-lasting for Søren's sense of himself, his authorship, and the audience to whom he was writing. It also led to a renewed fascination with what it means to stand apart as a witness to the crowd. “

It is frequently said

that if Christ came to the world now he would once again be crucified. This is not entirely true. The world has changed; it is now immersed in âunderstanding.' Therefore Christ would be ridiculed, treated as a mad man, but a mad man at whom one laughs.”

Søren had always known he was singular. Now he was beginning

to see himself as a type of potential martyr or witness to the truth. “

What Christendom needs

at every moment is someone who expresses Christianity uncalculatingly or with absolute recklessness,” runs an 1848 entry. “He is then to be regarded as a measuring instrumentâthat is, how he is judged in Christendom will be a test of how much true Christianity there is in Christendom at a given time.” Søren continues, “If his fate is to be mocked and ridiculed, to be regarded as mad, while a whole contemporary generation of clergy (who, note well, do not dare to speak uncalculatingly or recklessly) is honoured and they are also regarded as true Christiansâthen Christendom is an illusion.” Søren is clear in his reflections that his martyrdomâif martyrdom it beâis not for

Christianity

as much as it is for

“the truth.”

The one who presents the truth of the situation as completely and faithfully as he can has made no judgements about his own or anyone else's Christianity, but he has provided the opportunity for a clear choice to be made. “

The judgment

is not what he says but what is said of him.”

The intensified direction of Søren's vocation follows his tentative “conclusion” to the authorship and coincidental “unmasking” in the

Corsair

. Søren was self-conscious about how the loss of his trial at the court of popular opinion marked a new chapter in his life. Literally. On March 9, 1846, he began a new journal with a new system of notation. Each volume was labelled “NB” (from the Latin

nota bene

meaning ânote well') and successively numbered, eventually running to thirty-six books in all. Unlike the pre-

Corsair

journals, which tend to be a jumble of haphazard thoughts and rough drafts, the NB volumes are clearly written with an eye to future readership and often aspire towards a coherence unseen in the earlier journals. A common theme is Søren's reflection on his own mission, as an author and as a witness. Another theme is that of the nature of the Single Individual, Christ, and authentic Christianity. Another is the many “collisions” the trajectory of his life against Christendom was putting in his way. The long, opening entry of the first volume titled “

Report

” sets the tone. “

The Concluding Postscript

is out; the pseudonymity has been acknowledged . . . Everything is in order; all I have to do now is to keep calm, be silent, depending on the

Corsair

to support the whole enterprise negatively, just as I wish.” The Report describes the events from Søren's point of view, straining to put the mockery in as best a light as possible, but he admits “

this existence

is exhausting; I am convinced that not a single person understands me.” Søren is frustrated by the fact that people might think it was because of the

Corsair

that he had ended his authorship, and he is chagrined that luminaries like Bishop Mynster might think he adapted his books for the express purpose of engaging with the low tabloid. Instead, Søren insists the opposite is true. It only looks like he has inserted

Corsair

-specific passages into the

Concluding Unscientific Postscript

because his analysis of the state of things was so astute. The

Corsair

has merely brought to light what was always present in the culture. Søren ends the entry with a reiteration of his conviction that his authorship is concluded, and he expresses the wish once again that he might retire to a quieter life. “

If I only could

make myself become a pastor. Out there in quiet activity, permitting myself a little productivity in my free time, I shall breathe easier, however much my present life has gratified me.” Søren's hesitancy is evident even in the passages where he claims this is what he wants. Despite his occasional assertions that a country parish is the life for him, Søren is too aware of himself and too concerned with truth to push the matter very far.

A visit to

Bishop Mynster

in the autumn of 1846 confirmed to Søren he was bound for something other than church life. Ironically, it was Mynster's approval of Søren's plan for a pastorate that set the wheels turning. Mynster encouraged Søren to seek a living somewhere in the country. The response immediately put Søren on guard. He sensed Mynster agreed in some way with the treatment Søren was currently receiving at the hands of the

Corsair

rabble, thinking it would do him some good. A spell in a rural parish would take Søren down another peg or two and set him on a more respectable career in the church. These were decidedly not Søren's feelings towards either the

Corsair

or churchmanship. “When

Bishop Mynster advises me to become a rural pastor, he obviously does not understand me.” Despite the slight to his father's memory years before, Søren retained the habitual Kierkegaard family reverence for Mynster. Yet at the same time he suspected the bishop had less than pure motives for encouraging Søren to leave Copenhagen. Søren was trouble and Mynster knew it. It would not hurt the old bishop to get the annoying author out of the way. Søren would continue to occasionally meet with Mynster over the coming years, but more often than not the truncated visits would prove dissatisfying. Mynster was clearly not keen to maintain a relationship with his former parishioner's quarrelsome son and he kept Søren at arm's length.

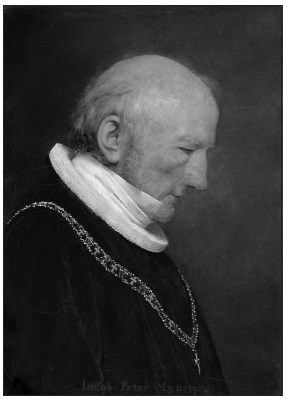

Jakob Peter Mynster, bishop, pastor to the Kierkegaard family and erstwhile mentor to Søren. “You have no idea what sort of poisonous plant Mynster was. . . . He was a colossus. Great strength was required to topple him, and the person who did it also had to pay for it.”

The reason is not hard to fathom. Søren's books during this time were filled with hidden and not so hidden critical allusions to Mynster, the church, and the Christian culture over which he presided as primate. And there were a lot of books. Both Søren's plan to take up a pastorate and his idea that his authorship was concluded came to nothing in the years following the

Corsair

. Between 1846 and 1854, under his own name, Søren brought out

Two Ages

,

Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits

,

Works of Love

,

Christian Discourses

,

The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air

,

Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays

,

On My Work as an Author

, and

For Self-Examination

. Neither did the practice of pseudonymity cease. Newly invented characters were assigned to

The Sickness Unto Death

,

Two Ethical-Religious Essays

,

The Crisis and A Crisis in the Life of an Actress

, and

Practice in Christianity

. Other substantial books did not see the light of day in Søren's lifetime:

The Point of View for My Life as an Author

,

The Book on Adler

,

Armed Neutrality

, and

Judge for Yourself!

were written but not published in this period. Newspapers received open letters, old journals were edited, the thirty-six volumes of the NB journals continued apace, and Søren prepared

Either/Or

,

Works of Love

, and some other texts for their second printing. Far from representing the nadir of his creative life, the years following the conclusion of the first authorship saw an explosion of productivity.

Søren's connection to the voluminous output was now common knowledgeânot only for the likes of Heiberg and Mynster but also for all the butcher boys and fishwives in town. In the past, Søren had been able to walk and talk on the streets as a way of keeping a necessary distance between himself and the serious ideas emanating from Victor, Hilarius, Johannes, and the rest. Now, thanks to the

Corsair

, Søren's public personae was no longer separate from his authorship. For the chattering classes obsessed with trousers, his physical presence effectively

was

the authorship. As a result, Søren embarked on a self-conscious effort to reconstruct his image. He took his walks in the empty countryside and, when in the crowded city, tended to stay at home. Søren avoided visitors

even more than before. “

And now that I

have remodelled my external life, am more withdrawn, keep to myself more, have a more momentous look about me, then in certain quarters it will be said that I have changed for the better.”

The self-examination that flowed from reflection on the

Corsair

and his dawning realisation that the authorship was not concluded after all saw Søren become more interested in the ways and means of communication and his role as a communicator. Already, before the

Concluding Unscientific Postscript

, Søren had intended to publish a book-length review of a novel by Heiberg's talented mother, Thomasine Gyllembourg. Søren told himself that writing a book review of Madame Gyllembourg's

Two Ages

did not count as being an author, as he was dealing mainly with another person's thoughts. The resulting book, whose full title was

Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age, A Literary Review

was half an appreciation of the novel, and half a platform for Søren's own musings on, amongst other things, the present age and its tendency to prefer chatter to meaningful communication and action. The public's predilection to “level” anyone who stands apart from the crowd is also subject to the full force of Søren's considerable critical faculties. What began life as a book review ended as a full length rejoinder to the spirit of the

Corsair

at work in the world.

The “book review” loophole also led to another of Søren's enduring pet projects. In the end,

The Book on Adler

would never be published in his lifetime, but this was not before the manuscript underwent more revisions and rewrites than anything else in the Kierkegaardian canon. Søren received Adolph Peter Adler's latest works in 1846 and began reflecting on them immediately. By the next year he had amassed over 200 pages considering the case of the errant pastor. Adler was a friendly acquaintance of Søren's, a university contemporary who had also studied theology, and had made his mark as a pro-Hegelian. However, in 1840, Adler had a religious experience after which he claimed that God wanted him to promote a new doctrine in opposition to the Hegelian influence

at work in Danish Christianity. Adler was widely chastised for his mystical enthusiasm and was forced to retire his parish. In the face of mockery and rejection, Adler then attempted to adapt his new revelation back along Hegelian lines.