Kierkegaard (23 page)

Authors: Stephen Backhouse

In the splendid cathedral

the Honourable Right Reverend Private Chief Royal Chaplain comes forward, the chosen favourite of the elite world; he comes forward before a chosen circle of the chosen ones and, deeply moved, preaches on the text he has himself chosen, “God has chosen the lowly and the despised in the world”âand there is no one who laughs.Is this the same teaching, when Christ says to the rich young man: Sell all you have and give to the poor, and when the pastor says: Sell all you have and give it to me?

One cannot live on nothing. One hears this often, especially from pastors. And the pastors are the very ones who perform this feat: Christianity does not exist at allâyet they live on it.

The Master of Irony kept a twinkle in his eye. Søren's friends report that during this time of scathing print satire, in person he was warm, jolly, and personable. Hans Brøchner met Søren on the street. “

With the greatest clarity

and calmness, he spoke of the situation he had provoked,”

Brøchner recalls. “He was able to retain not only his usual equanimity of mind and cheerfulness but even his sense of humour.”

The ninth issue of the

Moment

emerged on September 24, 1855. The next day, on a loose sheet of paper tucked into the journal, Søren scribbled a few reflections on his life and task. The entry concluded:

. . .

But what, specifically

, does God want? He wants souls able to praise, adore, worship, and thank himâthe business of angels. Therefore God is surrounded by angels. The sort of beings found in legions in “Christendom,” who for a few dollars are able to shout and trumpet to God's honour and praise, this sort does not please him. No, the angels please him, and what pleases him even more than the praise of angels is a human being who in the last lap of this life, when God seemingly changes into sheer cruelty and with the most cruelly devised cruelty does everything to deprive him of all zest for life, nevertheless continues to believe that God is love, that God does it out of love. Such a human being becomes an angel. . . . And every time he hears praise from a person whom he has brought to the extremity of life-weariness, God says to himself: This is it. He says it as if he were making a discovery, but of course he was prepared, for he himself was present with the person and helped him insofar as God can give help for what only freedom can do. Only freedom can do it, but the surprising thing is to be able to express oneself by thanking God for it, as if it were God who did it. And in his joy over being able to do this, he is so happy that he will hear absolutely nothing about his having done it, but he gratefully attributes all to God and prays God that it may stay that way, that it is God who does it, for he has no faith in himself, but he does have faith in God.

It was Søren's last act of writing. Late in the month, at a party at Giøwad's, Søren had another of his fits. He fell off a sofa onto the floor, waving away the alarmed offers of help. “

Oh, let me lie

here till the girl

sweeps up in the morning,” he joked, before fainting with exhaustion. A few days later Søren collapsed again, this time in the street. On October 2 he checked himself into the Royal Frederik's Hospital. Whether it was delicious irony or chagrin that Søren felt when he was assigned to the “

Mynster wing

” we will never know.

The diagnosis remained uncertain, but Søren was treated for paralysis of the lower half of his body. Tuberculosis of the spine marrow was suspected with the hospital notes including a prominent question mark after the word “tuberculosis.” He was given various medicines to aid his urination and chronic constipation. His legs were subjected to electrical stimulation, to little effect. “

The doctors

do not understand my illness,” said Søren to the visiting Emil. “It is psychical and now they want to treat it in the usual medical fashion.”

Emil asked his friend how it was going.

“Badly. It's death. Pray for me that it comes quickly and easily.”

How does Søren stand with Regine?

“It was the right thing that she got Schlegel, that had been the earlier understanding, and then I came in and disturbed things. She suffered a great deal because of me.” (Emil records that Søren said this last “lovingly and sadly.”)

Emil asks, “Are you angry and bitter?”

“No, but sad, and worried, and extremely indignant with my brother Peter. . . . I wrote a piece against him, very harsh, which is lying in the desk at home.”

There are lots of other papers at home, including a complete manuscript of the

Moment

number 10, ready to go to the printers, but Søren does not want to bother with them now. His money and his health lasted just long enough for him to get out all the issues he wanted.

“How strange that so many things in your life have just sufficed!” exclaims Emil.

“Yes,” agrees Søren. “And I am very happy about it, and very sad, because I cannot share my joy with anyone.”

Formerly Royal Frederik's Hospital. Søren Kierkegaard was admitted here on October 2, 1855.

Apart from Emil, Søren restricted his visitors to family members. Henrik Lund took pains to assure Søren that he would take care of money matters and anything else he needed. To this Søren replied, “

I have enough

. Enough to cover things admirably. Just like your old friendship, for which I sincerely thank you.” His niece Henriette, keen to counteract the impression that her beloved uncle was a crabbed and angry man, makes a point of recalling how upon entering the sickroom, she encountered a glow that practically shone from his face, giving the impression of

victory

mixed with pain and sadness. Nephew Troels reported that Søren had not lost his sense of humour. One day Søren

reluctantly agreed to a visit from the boy Troels and Johan, his brother-in-law. Johan Lund was clearly nervous in the presence of illness, and in his hale and hearty fashion exhorted Søren to change his posture and all would be well. “

Just straighten

your back and stand up and the sickness will disappear! I can tell you that!” During the embarrassed silence that followed, Troels sneaked a peek at his uncle, who winked back at his co-conspirator with a look of tolerance and a subversive sense of fun. Søren brought his awkward visitor back onto an even keel, and it was time for the party to take their leave. Troels was the last to exit the room. Søren took his hand and looked into his eyes. “Thank you for coming to see me Troels! And now live well!” For the nephew, everything was concentrated in the flood of light that came from the eyesâ“profound love, beatifically dissolved sadness, an all-penetrating clarity, and a playful smile.”

One family member never made an appearance. There are many letters from assorted uncles and nephews to Peter Kierkegaard, updating him on Søren's decline and urging him to come quickly. Finally, Peter arrived at the hospital on October 19, but in the end he was denied entry.

My brother cannot be stopped by debate, only action, Søren told Emil that day. Apart from their old familial conflicts, one of the current pressing issues was the matter of a final Communion, which Søren clearly feared his clergyman brother would force on him.

“Won't you take Holy Communion?” asked Emil. He too was ordained, after all.

“Yes. But not from a pastor, from a layman.”

“That will be quite difficult to arrange.”

“Then I will die without it. We cannot debate it. I have made my choice. I have chosen. The pastors are civil servants of the Crown and have nothing to do with Christianity.”

Emil was filled with pastoral concern for his friend but clearly also had an eye on making a report to history. A day earlier, he had enquired whether Søren believed in Christ and took refuge in him.

“Yes, of course, what else?” came the bemused reply.

But would you change anything, anything at all of what you said? Would you be less stringent?

“That is how it is supposed to be, otherwise it does no good. I certainly think that when the bomb explodes it has to be like this! Do you think I should tone it down, by speaking first to awaken people, and then to calm them down? Why do you want to bother me with this!”

“You have no idea what sort of poisonous plant Mynster was.” Søren continued. “You have no idea of it; it is staggering how it has spread its corruption. He was a colossus. Great strength was required to topple him, and the person who did it also had to pay for it.”

On October 27, Søren was lying down, incapable of speaking. Emil had to take his final leave and went back to his congregation, wife, and son.

“Søren Kierkegaard died in this building 11 November 1855.”

For the next few days Søren slipped in and out of consciousness. He could not eat or drink and he recognised no one. Finally, he fell into a comatose state. Søren Aabye Kierkegaard died at nine in the evening of Sunday, November 11, 1855. He was forty-two years old.

A Life Continued

The complete story of how Kierkegaard got to the world outside of Copenhagen would take volumes to fill, each longer than the tale of his life. Instead, if we imagine Søren's story told as a movie, then it might end something like this, with a montage of people and places running over the credits.

Our image opens with a shot of a spinning globe. Red lines begin from Denmark and arc to Norway, Sweden, and Germany. From there they jump to France, Italy, Spain, and Great Britain. Longer red lines traverse the ocean to Canada and the United States. But even this image, as intricate as it looks with all its red lines leaping, is too simplistic. There are a few false starts to the globe hopping. The name of Kierkegaard had been read in Scotland before most people saw it in Germany. It was heard in the great plains of middle America before Danish school children started reading Kierkegaard in their textbooks. The litany of languages and cultures is also too narrow. We must imagine smaller red lines springing into and out of places such as Mexico, Brazil, China, Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Bosnia and Latvia, and beyond. There are Muslim, Arab, and Persian Kierkegaard students and ongoing projects to translate his works into Turkish. Japan has enough Kierkegaard scholars to form rival schools of interpretation. And so it goes.

But our image will have to do.

1852. United Kingdom. One of the earliest international notices about Kierkegaard occurred within his lifetime. The Scottish traveller Andrew

Hamilton had spent a lot of time wandering around Denmark. In his travelogue

Sixteen Months in the Danish Isles

he paints a number of pen portraits of Copenhagen characters:

There is a man

whom it is impossible to omit in any account of Denmark, but whose place it might be more difficult to fix; I mean Søren Kierkegaard. But as his works have, at all events for the most part, a religious tendency, he may find a place among the theologians. He is a philosophical Christian writer, evermore dwelling, one might almost say harping, on the theme of the human heart. There is no Danish writer more earnest than he, yet there is no one in whose way stand more things to prevent his becoming popular. He writes at times with an unearthly beauty, but too often with an exaggerated display of logic that disgusts the public. All very well, if he were not a popular writer, but it is for this he intends himself.

It is Kierkegaard's first mention in English. It does not spark a wave of interest.

1855. Denmark. Henrik Lund's contribution to keeping his uncle's memory alive did not stop with his graveside protest. After Søren's death, the young doctor takes it upon himself to act on behalf of the literary remains, of which there are a lot. What he finds is “

a great quantity of paper

, mostly manuscripts, located in various places.” Henrik makes a desultory stab at arranging some of Søren's papers and letters, but it all proves too much. He begs Søren's best friend, Emil Boesen, for help. Perhaps Emil is busy, perhaps he is tired of acting as Søren's literary spy and lapdog, but in any case, he resists the temptation to bury himself in Kierkegaardiana. Eventually in 1857, the papers make their way to Peter Kierkegaard, who, on Martensen's recommendation, is now the newly installed Bishop of Aalborg.

1856. Denmark. Søren Kierkegaard's library, household goods, and assorted possessions are put up for auction. One lucky taker is Mogens

Abraham Sommer, who snaps up a walking stick. Sommer, a Jewish convert to Christianity with a line in schoolteaching, herbology, and itinerant preaching, considers himself a prophet in the Kierkegaardian vein. He uses the staff in his endless missionary trips around the countryside stirring up congregations against their established clergy. Sommer also attacks Martensen in print and gets into trouble with the law for libel. In 1860 Sommer travels to America, where he helps other Danes migrate to the Midwest and where, presumably, he continues to preach his heady mix of Kierkegaard, homeopathy, and Christian socialism.

1859. Denmark. Peter Kierkegaard publishes Søren's

Point of View

, the work in which, amongst other things, Søren retroactively spells out the Christian purpose of his career guided by Governance, a “report to history” helped by some creative juggling of the publishing record. Six years pass with nothing more forthcoming.

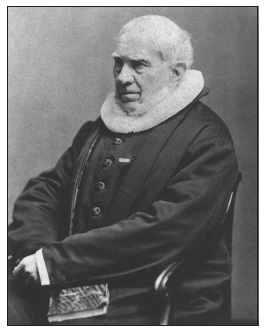

Peter Christian Kierkegaard, Søren's brother and last surviving Kierkegaard. In 1875 he relinquished his position as bishop, citing 1 John 3:15 in his resignation letter. Peter died as a ward of the state in 1888.

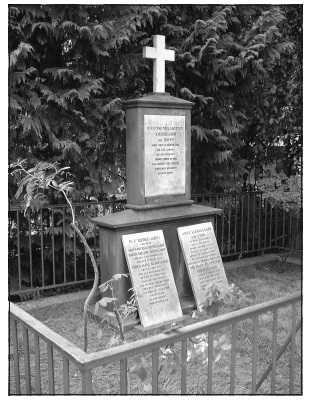

The Kierkegaard family grave in Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen. Søren is surrounded by family members. His inscription, leaning against the headstone, reads: “In a little while / I shall have won, / Then the entire battle / Will disappear at once. / Then I may rest / In halls of roses / And unceasingly, / And unceasingly / Speak with my Jesus.”

1865. Denmark. Peter enlists his secretary, the former journalist H. P. Barfod, to sort out the papers. Barfod discovers lots of juicy titbits, including the story of father Michael's hilltop cursing of God and evidence that Søren deliberately destroyed pages of his diary he knew would reveal too much of his secret sadness. Barfod is an assiduous editor who thinks of his work on the journals as laying bare the “

colossal and clandestine

workshop of the soul.” It is also he who had the foresight to collect the valuable memoirs of Søren's school chums and contemporaries. However, Barfod and his assistant Hermann Gottsched are responsible for a lot of

irreparable confusion. Søren's older, pre-

Corsair

journals were in various states of disarray and seemed incongruous next to the “NB” volumes. Barfod and Gottsched transcribe and arrange the material according to a scheme of their own devising and thenâincrediblyâdestroy the originals. The first collection of papers and letters are published in 1869. The series will eventually run to eight volumes. The publication of the papers and posthumous material leads to a new wave of interest in Søren Kierkegaard. The books sell well, and Peter as literary executioner donates the money to charity. Peter is dogged by indecision about his priestly vocation, guilt over his actions towards his brother, and envy of Søren's success. His mental health deteriorates. In 1875 Peter resigns his bishopric and later hands over his royal decorations. In a move that recalls his reason forty years ago for not taking Communion, he quotes 1 John 3:15 in his resignation letter: “Anyone who hates a brother or sister is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life residing in him.” Peter dies as a ward of the state in 1888.

1866. Norway. Henrik Ibsen publishes

Brand

, a play about an uncompromising Lutheran pastor with reforming zeal. The next year he brings forth

Peer Gynt

. Ibsen read Kierkegaard and knew his story but was cagey about attributing influence. Regardless of Ibsen's protests, the Kierkegaardian connections are widely assumed. Many readers and writers will later claim that the line of Kierkegaard came to them through Ibsen, including the American translator Howard Hong, the Irish novelist James Joyce, and the Spanish philosophical playwright Miguel de Unamuno, who liked to boast that he taught himself Scandinavian languages to read Ibsen, but found Kierkegaard instead.

1871. Denmark. If one were to ask a nineteenth-century British reader to name a famous Danish philosophical and theological writer, a likely name that would come up might be Hans Lassen Martensen. Bishop Martensen is a (relatively) popular figure abroad. His major works were translated into English in his lifetime, including the

Dogmatics

that had so infuriated Kierkegaard. Apart from one newspaper rejoinder,

during Kierkegaard's final feud with the Establishment Martensen had kept schtum, much to Søren's contempt. Now Martensen has broken the silence, devoting twenty or so pages of his recently published

Christian Ethics

to laying out and then refuting Kierkegaard's views of sociality and identity. The book is translated into English in 1873 by the Scottish

publisher T&T Clark. So it is that

Martensen, by answering Søren at last, brings the first extended discussion of Kierkegaard to the English-speaking world. Still, the wave of interest is not sparked. It will take more than this to get the red lines of Kierkegaard arcing over the map of the world.

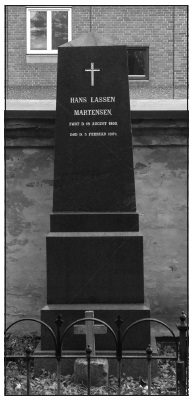

Bishop H. L. Martensen's grave, Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen

1877. Denmark. George Brandes is not a supporter of Kierkegaard, but he is the first person in the world to publish a major treatment of Kierkegaard's life and thought. Brandes's aim is to separate what he thinks is good about Kierkegaardânamely the attack on Christendomâfrom what he thinks is badânamely the Christian purposes for which Kierkegaard made his attack. It is largely through Brandes that word of Kierkegaard reaches Austria and Germany. For many years the most extensive German translations are taken from Kierkegaard's post-1850 writings, where they are used as fuel for local anticlerical movements.

1888. Germany. Frederick Nietzsche receives a letter from his friend Brandes, recommending that he take a look at Kierkegaard's writings. Nietzsche is intrigued and pledges to seek them out. Before he can do so, he suffers the mental breakdown that will lead to his death.

1896. Denmark. Fritz Schlegel, former governor in the West Indies and lately returned to Copenhagen, dies. His widow, Regine, begins to grant interviews to scholars, biographers, and members of the public hungry for fresh information about Kierkegaard. The conversations all begin with admiration for Fritz, but end with Søren. It is no easy thing being once engaged to Denmark's greatest polemical poet, and Fritz knew what a singular person he had in Regine. Fritz harboured no petty jealousy but instead did all he could to support his wife through it all. Regine would often exclaim to interviewers, “

Oh, that he could ever forgive me

for being such a little scoundrel that I became engaged to the other one.” Of Søren himself, Regine is unfailing in her defence and rebuffs any attempts at vilification. The only thing Regine is insistent on correcting is Søren's insinuation that she was not

religiously serious

. Regine dies in 1902, with the full realisationâas Søren had predictedâthat she had been taken with him into history.