King George (10 page)

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

A

cross the Delaware River from the American camp was the small town of Trenton, New Jersey. This was one of many towns now in the hands of the British army.

cross the Delaware River from the American camp was the small town of Trenton, New Jersey. This was one of many towns now in the hands of the British army.

Guarding the town were about twelve hundred German soldiers. Americans called them “Hessians” because many of them came from the Hesse region of Germany. The Hessians took over most of the houses in Trenton and made themselves comfortable. “My friend Sheffer and I lodge in a fine house belonging to a merchant,” wrote one officer.

This kind of invasion should get you out of school, right? Not if you went to Mistress Rogers's School for Young Ladies in Trenton, which stayed open all winter. We know this from letters that were sent to students that year. William Shippen, for instance, wrote to his daughter Nancy, age thirteen, saying:

“My, dear Nancy: I was pleased with your

French letter which was much better spelt than your English one, in which I was sorry to see four or five words wrong ⦠Take care, my dear girl, of your spelling and your teeth.”

French letter which was much better spelt than your English one, in which I was sorry to see four or five words wrong ⦠Take care, my dear girl, of your spelling and your teeth.”

And while most families got out of Trenton when the enemy arrived, a few stayed to try to protect their homes. A ten-year-old girl named Martha Reed stayed in town with her mother and younger brotherâher father was off in the Continental army.

Martha later described the cold mid-December night that the enemy showed up at her door. “Mother and we two children were gathered in the family room,” she said. “A great fire blazed in the chimney place ⦠Suddenly there was a noise outside, and the sound of many feet. The room door opened and in stalked several strange men.”

After warming up by the fire, the Hessian soldiers opened the storeroom and ate all the pickles and jarred vegetables. A bit later, they killed a hog and butchered it on the dinner table.

Even though Martha's mother spoke no German, she somehow managed to convince the soldiers that her husband was serving in the British army. So the Hessians agreed to let the Reeds stay in the house.

A few days later a child's coat gave the Reeds away. Martha explained: “To please my little brother, my mother had made for him an

officer's coat of the rebel buff [gold] and blue, in which he delighted to strut and fight imaginary battles.”

officer's coat of the rebel buff [gold] and blue, in which he delighted to strut and fight imaginary battles.”

When the Hessians found this coat, they knew they'd been tricked. They were in the home of Patriots! “What a storm broke around us!” Martha said. “They shook the little coat in our faces, jabbering and threatening.”

Martha's mother pulled the children outside and they all hid in the hen houseânormally a bad hiding place, since chickens cluck and cackle when they're disturbed. Luckily, the soldiers had already eaten all the chickens.

Martha and her family spent a freezing and frightening night in the empty hen house. “That was a night I can never forget,” she said.

I

n command of the German forces in Trenton was Colonel Johann “the Lion” Rahl. Bravery in battle earned Rahl his nickname. But he was also kind of a lazy guy. He liked to stay up late drinking and playing cards. Then he would sleep late and spend the rest of the morning in the tub.

n command of the German forces in Trenton was Colonel Johann “the Lion” Rahl. Bravery in battle earned Rahl his nickname. But he was also kind of a lazy guy. He liked to stay up late drinking and playing cards. Then he would sleep late and spend the rest of the morning in the tub.

“There were times,” complained one of his officers, “when we would go to his quarters for the morning formation between ten and eleven o'clock and he would still be sitting in his bath.”

Rahl was warned that the Americans might try to attack his army. He laughed and shouted, “Fiddlesticks! These clodhoppers will not attack us.” Rahl knew the Americans were starving, freezing, and ready to go home.

He expected to enjoy a quiet winter at Trenton.

T

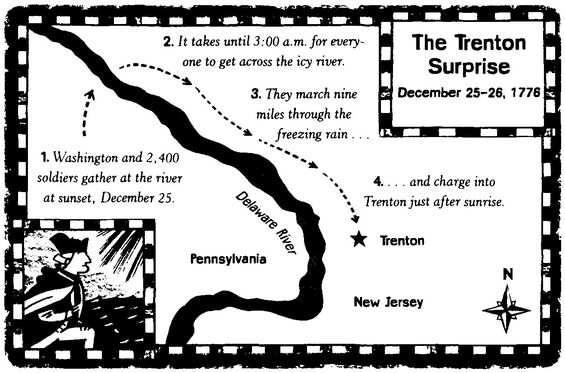

he sun set at 4:35 on December 25. Christmas Day had been sunny and cold, about thirty-two degrees. Now clouds covered the stars and a miserable mixture of freezing rain and snow started falling.

he sun set at 4:35 on December 25. Christmas Day had been sunny and cold, about thirty-two degrees. Now clouds covered the stars and a miserable mixture of freezing rain and snow started falling.

Washington ordered his soldiers to pack sixty rounds of ammunition and a three-day supply of salted meat and bread. Sixteen-year-old John Greenwood was one of the many soldiers who wondered where the army was going that night. He was hoping he wouldn't have to march too far, because he was suffering from a horrible rash on his legs. Or, as he put it:

“I had the itch then so bad that my breeches stuck to my thighs, all the skin being off, and there were hundreds of vermin upon me.”

John Greenwood

At least Greenwood had shoes. Many of the men had worn through theirs and had to tie rags around their bare feet.

The soldiers gathered at the edge of the Delaware River. They saw black water clogged with bobbing, swirling chunks of ice. And they saw John Glover and his fishermen waiting to row them across the river.

The boats started crossing and re-crossing the water. It took many trips to get everyone over. Colonel Henry Knox (the cannon expert) was determined to get eighteen cannons over the river also. “The floating ice in the river made the labor almost incredible,” he reported. “The night was cold and stormy; it hailed with great violence.”

John Greenwood was one of the first to cross the river. Then he stood on the New Jersey side, waiting for hours. “It rained, hailed, snowed, and froze, and at the same time blew a perfect hurricane,” he said. He and the other men pulled down fences and lit fires in a useless effort to keep warm. They watched the boats and waited.

Washington was watching and waiting too. “I have never seen Washington so determined as he is now,” an officer named John Fitzgerald wrote in his diary. “He stands on the bank of the river, wrapped in his cloak, superintending the landing of the troops. He is calm and collected, but very determined.”

The plan had been to get the army across the Delaware River by midnight. But thanks to the ice in the river, it took until three in the morning. Washington knew he would not be able to reach Trenton before dawn. “I determined to push on at all events,” he said.

The army began the nine-mile march to Trenton.

Y

ou often read about weather being a major factor in historical events. This was definitely true of the Trenton attack. On most nights, the Hessians in Trenton sent soldiers out to patrol the roads leading into town. But the night of December 25 was just too cold and nasty. The routine patrol was canceled.

ou often read about weather being a major factor in historical events. This was definitely true of the Trenton attack. On most nights, the Hessians in Trenton sent soldiers out to patrol the roads leading into town. But the night of December 25 was just too cold and nasty. The routine patrol was canceled.

So Colonel Rahl and his men were quite surprised when Washington and the Americans marched into town at about eight o'clock in the morning. Hessian soldiers grabbed their guns and ran out into the street. By the time they figured out what was going on, though, Washington's men already had the town surrounded. And Henry Knox had his cannons set up and ready to go. “These, in the twinkling of an eye, cleared the streets,” Knox reported.

There was absolutely nowhere for the Hessians to hide. They ran toward houses, but many of the women who had stayed in town suddenly stuck guns out the windows and starting firing.

The battle of Trenton was over quickly. Colonel Rahl was shot and killed. His entire army surrendered, except for a few men who managed to escape down the road. “This is a glorious day for our country,” Washington told his officers.

And to make the day even better, American soldiers found lots of good stuff scattered around town. John Greenwood took a German sword as a souvenir. An American drummer threw his own drum away and picked up a much nicer German one. Other soldiers put on fancy brass German officers' hats and strutted around town.

A

fter beating the Americans all year, British leaders in London had been sure they were about to win the war. “But all our hopes were blasted by that unhappy affair at Trenton,” said George Germain, King George's top war advisor.

fter beating the Americans all year, British leaders in London had been sure they were about to win the war. “But all our hopes were blasted by that unhappy affair at Trenton,” said George Germain, King George's top war advisor.

Washington wasn't done yet, though. He marched his troops to the town of Princeton and won another quick victory. These winter wins inspired thousands of new soldiers to join the army. The American Revolution was alive.

A Loyalist named Nicholas Cresswell was truly sorry to see the sudden change in the mood of Americans. “A few days ago they had given up the cause for lost,” Cresswell said. “Their late successes have turned the scale and now they are all liberty-mad again.”

But King George was still feeling confident. In fact, he had a new war plan. And he looked forward to crushing the Revolution in 1777.

The British General John Burgoyne celebrated Christmas in 1776 by placing a bet on the American Revolution. Burgoyne wagered fifty golden guineas that he could beat the Americans and “be home victorious from America by Christmas Day, 1777.” This was a bold bet. To win it, Burgoyne would have to cross the Atlantic, crush the Revolution, and get back to Londonâall in one year!

W

hat made General John Burgoyne so confident about crushing the American Revolution? Two words: the plan. Burgoyne had spent the past few months working out a detailed plan for winning the war. He presented the secret strategy to King George. The king loved it.

hat made General John Burgoyne so confident about crushing the American Revolution? Two words: the plan. Burgoyne had spent the past few months working out a detailed plan for winning the war. He presented the secret strategy to King George. The king loved it.

So in the spring of 1777, Burgoyne loaded cases of champagne onto a ship (he always traveled in style) and set out across the ocean with high hopes.

General Burgoyne arrived in Quebec, Canada, in early May. As soon as he got off the boat, he started hearing people talk about his socalled secret strategy. The Quebec newspaper even had an article about it, describing exactly how Burgoyne planned to defeat the Americans! As usual in this war, neither side could keep anything secret.

Burgoyne was annoyed, but not discouraged. So the Americans knew his planâso what? That didn't mean they could stop him.

The basic idea of the plan was simple: slice the United States in two. This would be done by attacking the centrally located state of New York from the north and south at the same time. Once the British controlled New York, all of New England would be cut off from the rest of the United States. The different regions wouldn't be able to help each other by sending soldiers or supplies back and forth. It would be like having an enemy's hands around your neck. The Revolution could be strangled.

L

ike everyone else, George Washington knew about Burgoyne's plan. But there was very little he could do. The British still had their main army, under the command of General William Howe, camped in and around New York City. Washington was worried that Howe would try to capture Philadelphia that year. So he had to keep his army nearby to prevent it. You can't just let the enemy capture your capital city, can you?

ike everyone else, George Washington knew about Burgoyne's plan. But there was very little he could do. The British still had their main army, under the command of General William Howe, camped in and around New York City. Washington was worried that Howe would try to capture Philadelphia that year. So he had to keep his army nearby to prevent it. You can't just let the enemy capture your capital city, can you?

A separate American army, known as the Northern Army, would have to stop Burgoyne's invasion. Washington couldn't send many soldiers to the Northern Army, but he could at least send one of his top generals. He picked a former merchant from Connecticut named Benedict Arnold.

Arnold had already fought in many of the war's fiercest battles, and he was known for his attacking style and reckless bravery. Here's

how one American soldier described Arnold's reputation in 1777: “He was our fighting general, and a bloody fellow he was. He didn't care for nothing; he'd ride right in ⦠. . He was as brave a man as ever lived.”

how one American soldier described Arnold's reputation in 1777: “He was our fighting general, and a bloody fellow he was. He didn't care for nothing; he'd ride right in ⦠. . He was as brave a man as ever lived.”

True, Arnold was also known as perhaps the most annoying man in America. His loud, bossy style made him almost impossible to work with. But this was no time to worry about personality conflicts. Washington needed a fighter in northern New York, so he sent his best one. “We have one advantage over our enemy,” Arnold said as he headed north. “It is our power to be free, or nobly die in defense of liberty.”

M

eanwhile, in Philadelphia, Ben Franklin packed up a lunch, climbed into a carriage with his two grandsons, and set off on a picnic. A picnic, Ben? At a time like this? Don't worryâit was part of a secret plan to help win the Revolution.

eanwhile, in Philadelphia, Ben Franklin packed up a lunch, climbed into a carriage with his two grandsons, and set off on a picnic. A picnic, Ben? At a time like this? Don't worryâit was part of a secret plan to help win the Revolution.

The plan was based on a simple fact, sad but true: the United States could not win this war without help. George Washington might win a small battle here and there, but the Continental army did not have enough soldiers, guns, and ships to defeat mighty Great Britain. What the Americans needed was a powerful ally. So Congress decided to try to persuade France to join forces with the United States. And Congress believed that seventy-one-year-old Ben Franklin was the man to do the convincing. Franklin was famous and highly respected in Franceâthey just might listen to him.

But first Franklin had to actually get to France. And with British spies snooping around every corner in Philadelphia, this was going to be a dangerous trip. If the British found out about Franklin's plans,

they would chase down his ship as it crossed the Atlantic Ocean. That would be the end of Ben Franklin.

they would chase down his ship as it crossed the Atlantic Ocean. That would be the end of Ben Franklin.

So Franklin and his two grandsons (William, age seventeen, and Benjamin, seven) rode out of town on an innocent little picnic. Then, when they saw they hadn't been followed, they drove the carriage to a small port on the Delaware River. All three of them climbed onto a waiting ship.

Six weeks later, they were safely in France.

B

attered and exhausted by the rough sea journey, Franklin had no time for rest. He and the boys jumped into a carriage and hurried toward Paris, the French capital. “The carriage was a miserable one,” Franklin remembered, “with tired horses, the evening dark, scarce a traveler but ourselves on the road.” And the dark road was far from safe.

attered and exhausted by the rough sea journey, Franklin had no time for rest. He and the boys jumped into a carriage and hurried toward Paris, the French capital. “The carriage was a miserable one,” Franklin remembered, “with tired horses, the evening dark, scarce a traveler but ourselves on the road.” And the dark road was far from safe.

“The driver stopped near a wood we were to pass through, to tell us that a gang of eighteen robbers infested that wood, who but two weeks ago had murdered some travelers on that very spot.”

Benjamin Franklin

Luckily, Franklin managed to avoid the French bandits. But the British spies spotted him right away. David Stormont, the British ambassador to France, rushed a report to his bosses in London. “I learnt yesterday evening that the famous Doctor Franklin is arrived,” wrote Stormont. “I cannot but suspect that he comes charged with a secret commission from the Congress ⦠. . In a word, my Lord, I look upon him as a dangerous engine.”

A few days later, young William Franklin went on an errand for his grandfather. He went to the French foreign minister's office and delivered a letter stating that Benjamin Franklin was here in Paris to negotiate a treaty of friendship between the United States and France.

The official French reply was basically “Well ⦠we'll think about it.” Sure, King Louis XVI and friends were still bitter about losing the French and Indian War to their old enemy Britain. The French were definitely hungry for a little revenge. They didn't want to join this new war, though, unless they were sure the Americans could actually win it. And so far, the Americans had lost most of the big battles. French leaders decided to wait and see how the fighting went in 1777.

Franklin settled in for a long stay in France. He couldn't accomplish much until there was some good news from home.

A

t first, there was no good news to report. Unless you were rooting for the British.

t first, there was no good news to report. Unless you were rooting for the British.

In July, General Burgoyne accomplished the first part of his plan: he captured Fort Ticonderoga from the Americans. This news delighted King George, who skipped into Queen Charlotte's bedroom, clapping and yelling, “I have beat them! Beat the Americans!”

The next step for Burgoyne's big army was to march about thirty miles from Fort Ticonderoga to the Hudson River. Things were going smoothly.

Baroness Frederika von Riedesel, for one, was having a wonderful time. Wife of the German general Friedrich von Riedesel, the baroness was one of hundreds of women who were traveling with Burgoyne's army (wives often went to war with their husbands in the 1700s). The baroness even brought her three young daughters along! As she wrote, this was an exciting opportunity for the family to see the world:

Baroness von Riedesel

“When the weather was good we had our meals out under the trees, otherwise we had them in the barn, laying boards across barrels for tables. It was here that I had bear meat for the first time, and it tasted very good to me.”

Then, just when everyone was having a fine time, the British started running into trouble. John Burgoyne (nicknamed “Gentleman Johnny” by his troops because he treated them well) insisted on living in luxury, even in the middle of a war. He needed thirty wagons just to haul all his champagne and fancy foods! This really slowed down the march, especially since the army was traveling over narrow paths through muddy, mosquito-filled forests.

And the Americans were doing a great job of making their British visitors feel unwelcome. American soldiers destroyed bridges and rolled boulders and logs into the road. They dammed up streams, causing them to flood the forest paths. Local farmers even burned their own crops, just to make sure the British wouldn't find anything to eat in New York.

Burgoyne was able to advance only one mile a day. By the beginning of September, his army was down to just a month's supply of food. And there was more bad news. You'll remember that Burgoyne's plan called for General William Howe to lead a second British army north from New York City. Now Burgoyne learned that Howe's army wasn't coming. General Howe had decided that he would rather attack Philadelphia than cooperate with Burgoyne's plan. (Howe didn't like Burgoyne. And since he outranked Burgoyne, he could do whatever he wanted.)

Gentleman Johnny was starting to sweat.

“When I wrote more confidently, I had not foreseen that I was to be left to pursue my way though such a tract of country and host of foes, without any cooperation from New York.”

John Burgoyne

The leaves on the trees of northern New York were just starting to change from green to yellow and orange. To Burgoyne, the colorful leaves were a painful reminder that it was getting late in the year. If he was going to turn and march his army back to safety in Canada, he had to do it right then, before winter weather made the trip impossible.

Burgoyne thought about it ⦠and decided to continue the attack. His army would try to fight its way south to Albany, where it could spend the winter indoors. “This army must not retreat,” he told his men. Was he thinking about that bet he had made back in London?

Other books

The Amorous Education of Celia Seaton by Miranda Neville

The Measures Between Us by Ethan Hauser

Colin Meets an Emu by Merv Lambert

House of Evidence by Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

Moloch: Or, This Gentile World by Henry Miller

Connection by Ken Pence

The Bad Boy's Baby (Hope Springs) by Cindi Madsen

My Family for the War by Anne C. Voorhoeve

Sleeper Spy by William Safire