King George (8 page)

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

Here's the big question of 1776: Are you for or against independence from Britain? You can put Benjamin Franklin down in the “for independence” column. After a lifetime of success as a writer, inventor, diplomat, and founder of colleges, libraries, fire departments, and about forty other things, Ben Franklin was the most famous American in the world. And now, going strong at age seventy, he was serving in Congress and urging the younger members (they were all younger) to make the break from Britain.

J

ust how strongly did Benjamin Franklin feel about American independence? He would do almost anything for the causeâeven share a tiny bed with John Adams. This happened one night when the two men were traveling together on important business for Congress.

ust how strongly did Benjamin Franklin feel about American independence? He would do almost anything for the causeâeven share a tiny bed with John Adams. This happened one night when the two men were traveling together on important business for Congress.

“But one bed could be procured for Dr. Franklin and me,” Adams explained, “in a little chamber little larger than the bed, without a chimney and with only one small window.”

Both men put on their nightshirts and climbed into the narrow bed. They tried to get comfortable. But Adams felt a cool breeze and he noticed the window was open. He always got cold easily. So he jumped up to shut the window. Franklin cried out, “Oh, don't shut the window! We shall be suffocated!”

Adams tried to explain that he was afraid the chilly night air might make him sick. But this was nonsense, Franklin insisted. “Come, open the window and come to bed, and I will convince you,” said Franklin. “I believe you are not acquainted with my theory of colds.”

There was no point arguing with Franklin. So Adams left the window open, leapt back into bed, and pulled the covers up to his chin. Then Franklin began a very long lecture on air and breathing and the true causes of colds ⦠. .

To Adams, this was better than any bedtime story. “I was so much amused,” Adams recalled, “that I soon fell asleep, and left him and his philosophy together.”

S

o John Adams and Ben Franklin couldn't share a bed peacefully. But they could agree that it was time for the thirteen colonies to declare themselves a free and independent country. What about the other three million colonists? Many of them still weren't convinced that independence was such a great idea. After all, they were proud to be part of the British Empire. What would it be like to be an American citizen? No one really knew how that would turn out.

o John Adams and Ben Franklin couldn't share a bed peacefully. But they could agree that it was time for the thirteen colonies to declare themselves a free and independent country. What about the other three million colonists? Many of them still weren't convinced that independence was such a great idea. After all, they were proud to be part of the British Empire. What would it be like to be an American citizen? No one really knew how that would turn out.

Thomas Paine, it's time for you to enter the story.

After spending his first thirty-seven years in Britain, Tom Paine sailed away from his homeland in 1774. He left behind several failed careers, two failed marriages, and a reputation as a clever but fairly annoying fellow. He was the kind of guy who would come over to your house and then stay for weeks, lazily lying around your living room and eating your food.

But when he felt like working, Paine had an amazing ability to write powerful and convincing arguments. He showed writing talent early in life, as you can see from this poem eight-year-old Tom wrote for his dead pet bird:

Here lies the body of John Crow,

Who once was high but now is low;

Ye brother Crows take warning all,

For as you rise, so must you fall.

Who once was high but now is low;

Ye brother Crows take warning all,

For as you rise, so must you fall.

When his boat arrived in Philadelphia, Paine was so sick from the journey that he had to be carried ashore on a stretcher. Not a good start. He recovered quickly, though, and soon found work writing for a few newspapers.

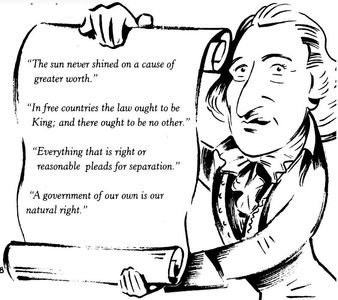

By early 1776, Paine was ready to write something big. Really big. He was sure the colonies should declare independence, and he wanted to convince Americans that they could make it on their own. So he published a pamphlet called

Common Sense,

which was filled with punchy lines like:

Common Sense,

which was filled with punchy lines like:

Thomas Paine

Common Sense

was a wild success. “I believe the number of copies printed and sold in America was not short of 150,000,” reported Paine with pride. George Washington soon noticed that Paine's writing was winning many Americans over to the side of independence. “I find

Common Sense

is working a powerful change in the minds of many men,” he said.

was a wild success. “I believe the number of copies printed and sold in America was not short of 150,000,” reported Paine with pride. George Washington soon noticed that Paine's writing was winning many Americans over to the side of independence. “I find

Common Sense

is working a powerful change in the minds of many men,” he said.

After years of failure, Paine finally could have made some money. Instead, he donated his

Common Sense

profits to the Continental army. He asked that the money be used to buy mittens for the soldiers. “I did this to do honor to the cause,” Paine said.

Common Sense

profits to the Continental army. He asked that the money be used to buy mittens for the soldiers. “I did this to do honor to the cause,” Paine said.

N

ow it was March 1776, and Abigail Adams was still waiting for a declaration of independence. She and the Adamses' five children were living at the family house near Boston. Abigail wrote frequently to John in Philadelphia, keeping him up to date on their family and friends. “The little folks are very sick and puke every morning,” she wrote in one letter. “But after that they are comfortable.”

ow it was March 1776, and Abigail Adams was still waiting for a declaration of independence. She and the Adamses' five children were living at the family house near Boston. Abigail wrote frequently to John in Philadelphia, keeping him up to date on their family and friends. “The little folks are very sick and puke every morning,” she wrote in one letter. “But after that they are comfortable.”

John wrote back with all the latest news from Congress. But his letters were always too short for Abigailâshe wanted more information. “You justly complain of my short letters,” John admitted. He said he was too busy to write more.

Abigail must have accepted this excuse, because she kept writing long letters to John. She knew that when the colonies declared independence, the new country would need a new government. And in a letter that later became famous, Abigail offered John some advice on what this government should be like:

“And by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will

be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.”

be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.”

Why should John “remember the ladies”? You probably know that women had few rights in those days. They couldn't vote, run for elected office, or attend college. And married women had to give up control of all their property to their husbands. Suppose a woman owned a farm, for example. Once she was married, her husband could sell the farm without her permission!

Abigail was ready for some changes. She even warned John that women might start a revolution of their own:

Abigail Adams

“If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment

3

a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation.”

3

a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation.”

Abigail was joking with John, but she was also expressing a serious idea. Too bad John wasn't quite ready. for

Abigail's ideas. “As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh,” he wrote to her.

W

e haven't checked in on King George in a while. Do you miss him?

e haven't checked in on King George in a while. Do you miss him?

As you might expect, the king was not waiting around to hear any declarations of independence. In a speech to Parliament, George declared the American colonies to be in an official state of rebellion. The king called Patriot leaders “wicked and desperate persons” and vowed to “bring the traitors to justice.”

To help get this done quickly, Britain needed more soldiers. So King George rented some from Germany. You can do that when you're a king. It worked like this: George paid German princes a lot of money, and the princes sent German soldiers to fight for Britain. And the princes actually got extra cash for every German soldier that was killed. You can do that when you're a prince.

In the spring of 1776 Americans started reading the shocking news: boats full of German soldiers were on their way west across the Atlantic Ocean!

How could King George do this?

colonists wondered.

How could he send foreign troops here to kill us?

How could King George do this?

colonists wondered.

How could he send foreign troops here to kill us?

King George had been hoping to stop a revolution. Instead, he actually made more Americans think it was time to declare independence.

A

nd Congress needed the shove. Let's let a member of Congress named Joseph Hewes sum up the mood in Philadelphia: “Some among us urge strongly for independence ⦠others wish to wait a little longer.”

nd Congress needed the shove. Let's let a member of Congress named Joseph Hewes sum up the mood in Philadelphia: “Some among us urge strongly for independence ⦠others wish to wait a little longer.”

These were tense times in Congress. Members spent twelve

hours a day (often without snack breaks) meeting in the hot, stuffy Pennsylvania State House. Then, at night, they continued working and arguing in taverns and inns.

hours a day (often without snack breaks) meeting in the hot, stuffy Pennsylvania State House. Then, at night, they continued working and arguing in taverns and inns.

These guys were not only debating independenceâthey were trying to help run a war too. Like his cousin John, Samuel Adams hardly had time to keep in touch with his family. “I can scarcely find time to send you a love letter,” Adams wrote to his wife.

By the middle of June, a majority of the members of Congress were finally ready to declare independence ⦠almost. You can't just wake up one day and say, “Okay, now we're independent.” You really need some kind of official declaration. You know, a written document that explains your reasons for becoming independent. What you need is a Declaration of Independence.

The members of Congress elected a five-man committee to write the Declaration: Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and a young lawyer from Virginia named Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was fairly new in Congress, and he hadn't spoken much so far. John Adams said of Jefferson: “The whole time I sat with him in Congress, I never heard him utter three sentences together.”

No, Jefferson wasn't much of a public speaker. He could write, though. And he was about to do some pretty good writing.

Thomas Jefferson

Other books

Prince of Time by Sarah Woodbury

A Sinful Calling by Kimberla Lawson Roby

The Underground Man by Ross Macdonald

Crossroads by Jeanne C. Stein

The Last Mile by Tim Waggoner

Alert: (Michael Bennett 8) by James Patterson

The Fish's Eye by Ian Frazier

The Jungle Books by Rudyard Kipling, Alev Lytle Croutier

Dating Daniel (Cloverleaf #4) by Gloria Herrmann

Stirring Attraction by Sara Jane Stone