Known and Unknown (7 page)

Authors: Donald Rumsfeld

The Last of Spring

I

n the desperate, hardscrabble years of the Great Depression, 1932 was, as the historian William Manchester described it, “the cruelest year” of them all.

1

Even resilient, industrial Chicago had not been spared the Depression's ravages. On the edge of the Loop, the city's downtown business district, thousands of those left unemployed and homeless constructed a Hooverville of scrap metal shanties and cardboard tents, named as such to disparage the president who was blamed for the economic woes. Alleys and streets were given new names like Prosperity Road and Hard Times Avenue.

2

On July 9, 1932, the

Chicago Tribune

noted grimly that the Dow Jones Industrial Average had closed the day before at 41. 22âthe lowest point recorded during the Great Depression. This was the day I was bornâon what may well have been the bleakest day of the cruelest year of the worst economic catastrophe in American history. Born in St. Luke's Hospital in downtown Chicago, I was the second child of George and Jeannette Rumsfeld. As I later recorded in my first and only other attempt at an autobiography (at age thirteen) I came home from the hospital to find I had a two-year-old sister, Joan.

3

Since my family moved a great deal during our early years, Joan tended to be a frequent playmate and one of my closest friends.

Our mother, Jeannette, was a small woman, but her stature belied a feisty intensity. A teacher by training, she was a stickler for proper grammar. While she was kindhearted, she was also a formidable taskmaster. One vivid memory of my mother occurred when we lived briefly in North Carolina. In the South teachers taught by rote, as opposed to the progressive education I was used to in Illinois, in which students were encouraged to learn at their own pace. As a result I was far behind my Southern classmates. When told that I was in danger of being held back a grade, Mom bridled. She told my teacher that I would attend summer school and that she would tutor me personally to get me up to speed. Every day, Mom and I went through drills to make sure I learned my division tables. It wasn't my favorite summer, but I learned enough to make it to the next grade.

My father, George Rumsfeld, was the kind of man any young boy would look to as a role model. I certainly did. He was the most honest and ethical person I knew, and I often sought his advice. One of the reasons he might have worked so hard to be a good father is that he knew what it was like not to have one. John von Johann Heinrich Rumsfeld left the family and divorced my father's mother soon after his birth. From an early age, it was up to my father and his older brother, Henry, to help support the family. Dad started as an office boy at the age of twelve and worked hard for most of his life, always with an upbeat manner, often whistling, and without complaint. He seemed to have a sense of urgency about things and was never one to waste time. Sometimes he'd take me to the public golf course near twilight for his version of speed golfâplaying nine holes in what I remember to be less than forty-five minutes, never stopping to take a practice swing.

My earliest years were spent in the city of Chicago, which by then had become known as a settling place for large numbers of European immigrants, industrious frontiersmen seeking a second chance at fortune, and for sizable numbers of African Americans, who emigrated from the South. Yet amid the city's diversity, Chicagoans shared a common trait: a decidedly unfriendly attitude to the pretensions of aristocratic Europe. Many in Chicago were Irish at the time, and local politicians gloried in mocking the English, and the British seemed to reciprocate. “Having seen it,” the British writer Rudyard Kipling sniffed after visiting Chicago, “I urgently desire never to see it again. It is inhabited by savages.”

4

There was some truth to the notion that the city was not for those with delicate sensibilities. The city gave America Al Capone, the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, the Black Sox Scandal of 1919, and its legendary machine politicsâdenizens of its cemeteries were known for voting early and often. Chicago's residents took a certain pride in their rough-and-tumble ways. It was a city where one's value was measured not so much by pedigree but by sweat. “Chicago,” American writer Lincoln Steffens once wrote, quite correctly, “will give you a chance.”

5

My father had spent most of his youth and first years of marriage in modest apartments in the city and was eager to move his family to a house in the suburbs. When I was six, we moved to nearby Evanston, home of Northwestern University, and then finally to a house in Winnetka, a small suburb to the north. These moves were not idle decisions but ones that my father, quite typically, had carefully thought through. Dad believed that the areas where the schools were considered the best tended to be areas where property values would increase. Winnetka, in the New Trier High School district, was such a place. We shared our house with Dad's mother, Lizette, and her mother, Elizabeth. The older women, who had raised Dad, often spoke to each other in German.

*

These days Winnetka is a well-to-do bedroom suburb of Chicago, but in the 1930s the town was economically diverse. Our neighborhood was a mix of businessmen with families and immigrant and working-class families: construction workers, a train conductor, an electrical power line worker, a gardener, and a cleaner among them.

I guess because my parents were energetic people, I must have inherited that characteristic at an early age. In addition to my studies, I played third base on Conney's Cubs, our village hardball team, which was sponsored by the local pharmacy. I joined the Cub Scouts when I was seven, and enjoyed excursions to hike, fish, and canoe. As far back as I can remember I had odd jobs. I was not yet ten when I determined that I would earn enough money for my first Schwinn bicycle. I delivered newspapers, mowed lawns, and sold magazine subscriptions, including the Norman Rockwellâcovered

Saturday Evening Post

. On Saturdays I earned a hefty twenty cents for delivering a neighbor's homemade sandwiches to the employees at the Winnetka Trust & Savings Bank. When I finally earned enough money for my red Schwinn, it seemed the most perfect thing in the world. For kids in our neighborhood, our bikes were freedom. We could go anywhere we wanted. At least until it was time to come home.

All in all, mine was a fairly typical childhood in a small Midwestern town in the 1930s. Before Pearl Harbor.

Shortly after the Japanese attack, my father volunteered to join the Navy. Dad was not an ideal recruit. He was thirty-eight years old, well past the age draft boards were seeking. He had a slight frame that made him appear frailer than he was. The Navy recruiting office turned him away.

Instead of giving up, Dad embarked on an effort to gain weight. He ate banana splits, milk shakes, and anything else that would pack on pounds. After undertaking this regimen, Dad went back to the recruiting office and tried again.

It may have helped him that the war was not going well. The recruiting office finally said yes and told the determined man with the German name to prepare to deploy for officer training. His decision meant a big change in our lives.

After his ninety-day training assignment in Quonset Point, Rhode Island, Dad was commissioned, and our family moved to a blimp base near Elizabeth City, North Carolina. Navy blimps were used to spot German U-boats stalking Allied merchant ships in the Atlantic. My father didn't want to spend the war in North Carolina though, and quickly requested a transfer to sea duty. Eventually his request was granted, and he was assigned to the USS

Bismarck Sea

(CVE-95), a baby flattop, or escort carrier, in the final phases of completion at a shipyard near Bremerton, Washington. Originally, my parents decided that the family would return to Illinois. But Mom didn't want to be that far away from Dad, and at the last minute she decided we would travel with him until he went out to sea. So we moved next to East Port Orchard, Washington, then briefly to Seaside, Oregon, while the ship was being completed.

In 1944, after the

Bismarck Sea

's shakedown cruise, the Navy transferred my father to the USS

Hollandia

(CVE-97), which was also preparing to deploy to the Pacific theater. The reassignment turned out to be fortuitous. After Dad went off to sea with the

Hollandia

, the

Bismarck Sea

was sunk by a kamikaze attack. More than three hundred people onboard were killed.

With our father at sea, my mother, like so many wives whose husbands were off at war, had to manage the family by herself. She learned to drive for the first time after Pearl Harbor, and wasn't particularly comfortable with it. Heading south from Oregon, we drove through San Francisco. Mom was so nervous about driving up and down that city's famous hills in our green 1937 Oldsmobile that she made Joan and me get out of the car and walk in case she lost control of the vehicle trying to work the clutch and floor stick shift.

Without having a chance to consult Dad, she bought a tiny house on C Avenue in Coronado, California, not too far from the naval air station. It was a big decision for her to make, with little money and less experience in such matters. Throughout the war, she was careful with purchases. Mom once wrote to my father that out of the $190 she had for the month, the family's expenses totaled $186.37.

*

We were fortunate to be in Coronado with so many other military families in roughly the same circumstances. Mom became good friends with the wives of others in the crew of the

Hollandia

. They shared their worries and their news with one another. Many of the kids I went to school with had fathers or older brothers deployed, so we shared a special bond.

We followed the news of the war by poring over maps in newspapers, listening to radio reports, and watching the short newsreels that played in movie theaters before the feature presentations. Everyone I knew in Coronado supported the war effort with a sense of common purpose. We planted Victory Gardens, where we grew our own vegetables. With earnings from odd jobs, I bought coupons or stamps for war bonds. I collected paper, rubber, and metal hangers to be recycled into war materials. My mother saved frying oil to be used for munitions. No one could buy new car tires, because rubber was being used for military vehicles, so old tires were retreaded. The government rationed such staples as gasoline, sugar, butter, and nylon. There were few complaintsâthere was a sense we were all in it together.

As the war went on, we would spot small flags in people's windows with a star that signified someone in that house was in military service. When a serviceman was killed, those flags would be replaced with ones that had gold stars.

My parents were not accustomed to being apart, and it wore on both of them. Mom wrote letters almost every day. Dad would respond on the thin, onion-skin paper known as V-mail, the “V” standing for victory. Sometimes letters would fall apart as they came out of the envelope, because parts had been cut out by the censors aboard the ship to avoid giving the enemy intelligence if the mail was intercepted. As a result, we never knew where Dad was or what he was doing, but we were happy to receive his letters because that way we knew he was safe.

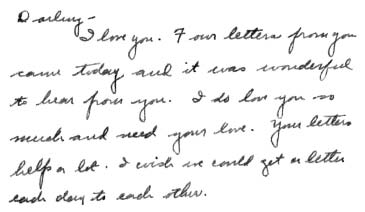

Letter from Jeannette Rumsfeld to George Rumsfeld, November 14, 1944.

“Well Darling, so long for now,” Dad wrote to my mother in August of 1944. “I love you and don't think I'll ever want to leave you or the kids again when this war business is over.”

7

Around my father's birthday, Mom wrote, “We didn't have cake on your birthdayâI didn't want it without you. We just thought of you all day and talked about you and thought you many birthday wishesâ¦. I want more time with youâall I can haveâand as soon as possible.”

8

Mom updated Dad on Joan and me. “[Don] is the type of person who needs to keep busy and he does keep busy,” she wrote in one letter. “Don said this evening at dinner that he has three ambitions. He would like to become a âband leader' like Harry James [at the time I played the cornet in the junior high school band]âan âarchitect' and a âflying Naval Officer.'”

9

As it turned out, I would only fulfill one out of three.