Kokoda (12 page)

MUD, MOSQUITOES, MALARIA AND MONOTONY

Only seasoned men of robust bodily fitness could be depended on to endure the rigours of even a few days marching and fighting in these latitudes [of New Guinea], where the moist heat hangs like an oppressive curtain and makes strenuous exertion for more than a few hours intolerable to the white man.

Official History of Australia in the Great War

The natives here are known as as Coons & speak a useful language— Pidgin English… The coons are rather intelligent & will do anything for you…

Salvation Army missionary, Jack Stebbings in Rabaul, 1941

As a general rule the edge of all garbage dumps around the world have the common feature that they are stinky and blowy. The curious feature of Port Moresby, it seemed to the newly arrived men of the 39th, was that this stinky, blowy edge looked to go clear to the core. From the moment their ship pulled into the town’s harbour after six days at sea, it was hot, humid and putrid, with their chief welcoming committee composed of swarms of flies. Morale sank even further as they looked about them. Moresby’s Fairfax Harbour, a wretched foreshore of dry grass mixed with indeterminate detritus, gave way to low, brooding hills on which lost little white weatherboard cottages with galvanised iron roofs clung grimly and forlornly. Many of these had their windows boarded up. The whole joint, crisscrossed by dusty little streets, just looked sad and desperate. Whatever else, it was no Pacific island paradise.

This was some kind of twentieth birthday, Joe Dawson thought, as he stared glumly to the shore. The only visual relief came by looking to their far north, where they spied something which impressed them, much as it had impressed the first European man who had given it a name. Back in 1850, British naval Captain Owen Stanley had been meandering along the southern coast of this strange land, in his ship the HMS

Rattlesnake,

when a mist which had rolled in from the south suddenly thickened to the point that nearly all was obscured. As it was clearly too dangerous to continue in such unknown territory, the second of Her Majesty’s ships on this exploratory trip—HMS

Bramble

, under the command of Lieutenant Charles Yule—led the way into a bay. But late in the afternoon, the mist lifted.

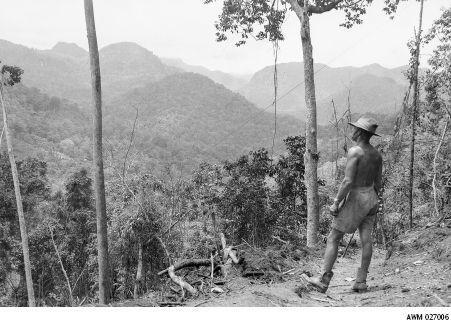

‘As if a curtain had been drawn up,’ Stanley would later write, ‘the mist and cloud suddenly lifted and the British seafarers gasped. Before them lay an extraordinary range of mountains, vaulting high to the heavens, with each of their peaks clearly shining in the last ebb of the afternoon sun.’ In the captain’s own honour, in the practice of the time, the peaks were named the Owen Stanley Range, and the highest of them, Mount Victoria (rising to 13 400 feet) was what the men of the 39th and 53rd could see now as they disembarked into the tiny boats which would take them into the shallow shore.

On terra firma again, the men stood around for some time as their nominal superiors met with the commanding authorities in New Guinea to discuss just where they would sleep for the night. Incredibly, it almost seemed as if the arrival of the

Aquitania

had been a surprise, because

nothing

had been done to prepare to receive them. Eventually it was decided that the still whining 53rd Battalion could make camp out on the Napa Napa Peninsula, right beside the mosquito-infested mangrove swamps. As to the 39th, they would have to make do with a kind of rough camping area beside the Seven Mile Airport, so named because that was its distance from Port Moresby’s port, which also served as the rough centre of town. Just a few months previously the area had been the town’s racecourse, until commandeered for the war.

Fall in. Move out. By the right… quick march!

Bit by bit as the soldiers marched, things were discarded as it became progressively clearer that this wasn’t Honolulu after all. Together with the sound of

left… left… left… left-right-left

of their boots, came the occasional ‘thump’ as fishing rods, cricket bats, tennis racquets and golf clubs were hurled into the bushes, and before long the homemade cello also bit the bitter dust.

Just where the hell were they? Was this really

it

! Yup, this was pretty much it. The 39th made camp the best they could beside a small area just to the southeast of ‘the camp’—and by God every sneering curl of those quotation marks was justified, because the ‘camp’ provided precisely no shelter or even shade of any kind. No barracks, no tents, no food, no mosquito nets, no quinine, no bloody nuthin’. There was not a single tap of fresh water, nor a single working toilet.

Sure, they had brought a lot of those things with them—some 10 000 tons of supplies in the hulls of both their own and accompanying merchant ships—but in their shambolic departure, all of the basic

matériel

had been loaded first. This meant it would be several days before it would emerge from the heavier equipment that had been loaded on top of it. Not the least of their problems was the lack of food and, for the first two days in Moresby, the newly arrived subsisted on the hardcore baked matter the men referred to as ‘dog-biscuits’, tins of beetroot, and gallons of tea which they boiled up in some empty kerosene tins they found on the nearby rubbish dump. Just who was the drongo running this man’s army?

His name was Major General Basil Moorhouse Morris and, whatever else, he at least

looked

the part of a great military commander. He was a big man with a large brown moustache and piercing eyes; he stood ramrod straight, was always impeccably turned out, and with his ever-present sun helmet and horsetail fly-whisk, he rather came across like an antipodean Lord Kitchener who would have been perfect for a poster saying: ‘I want YOU to serve in New Guinea.’ The effect was completed by the fact that he adored strutting around his well-appointed Army HQ bungalow well out of town, beneath the shade of a large Union Jack flag, saying truly magnificent things such as: ‘If necessary, Port Moresby must become a Tobruk of the Pacific!’

29

For all that splendid appearance and sound, however, he was not necessarily a man born to military command. Though he had been one of his good friend General Blamey’s first appointments— with Morris having been in the vanguard of Australian troops sent to the Middle East to set up facilities to receive the 6th Division— it had soon become apparent that that kind of work was not his forte. In Blamey’s own words, Morris had: ‘showed that he did not possess sufficient flexibility of mind to adjust himself readily to the needs of the occasion’ and the apparent backwater of New Guinea had been his next port of call.

30

Though Morris tended to specialise in dithering in most things, when it came to political infighting he proved to be very energetic indeed. And, as it turned out, at the time that the 39th and 53rd arrived, Major General Morris was never busier, engaged as he was in a bitter sectarian turf war with the man in charge of Port Moresby’s civilian administration, Leonard Murray. From the time Morris had taken command of the ‘8th Military district’ encompassing New Guinea, on 26 May 1941, he had moved forward on all fronts, while Murray had dug in just as bitterly, fighting to his last petty official and ink-blotter to keep primary control of the day-to-day running of the colony. It was the misfortune of the newcomers of the 39th and 53rd battalions that they arrived right when the fight was achieving its climax.

For look, with one thing or another, there simply hadn’t been

time

for Major General Morris to get things in shape for all the chaps arriving. When the desperate Australian Government came down heavily on the side of Major General Morris to try to resolve the dispute, it saw not only the complete withdrawal of Leonard Murray from the territory, but also the resignation of the very senior administrators and minor officials who had been keeping the wheels of government turning, however slowly. This would further worsen the situation not only for the newly arrived militia, but for all of the territory, as many native police deserted, hospitals closed down, and the rough judicial system ceased to function. As the Diggers were trying to settle in, the whole territory was teetering on the brink of anarchy with the collapse of the civil institutions.

To fill the vacuum left by the lack of civilian administrators Morris would soon create the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, whose job was to run the colony with a focus on native affairs and to ‘marshall and lead the native peoples in support of the Allied Armed Forces.’

31

ANGAU, as it became known, was essentially the section of the army responsible for ensuring that the environment in which the Australian soldier was operating would remain as stable as possible, and that the administration of native affairs across the land would continue as before.

Which was as well, because whatever else, Major General Morris certainly had many problems to deal with in these first days of 1942, many of them medical in nature. For there was no way around it. Apart from being an infernal nuisance and irritation to all concerned, the fact that in this particular part of the world swarms of flies on the day shift gave way to clouds of mosquitoes on the night shift, exacted a terrible toll on a body of men ill-equipped to defend itself against either. (One thing that at least slightly alleviated the bloody mossies was to throw green leaves onto a fire and then sit squarely in the middle of the resultant smoke, though this was very much a case of the cure quite possibly being worse than the ailment.) As to the flies, well, the Diggers didn’t like to boast, but many from Victoria’s rich cattle country had innately felt that when it came to dealing with flies, there was very little you could have taught them. Here though, in this Gawd-forsaken land, they had to take their hat off, and frequently did, to the sheer number of the little buggers. And the flies which weren’t buzzing around your person were always buzzing all over the food, such as it was, because in these conditions food went off in about three hours flat, sending out a siren call to every fly for miles around to come on over and buzz their filthy way all over it.

As to the mosquitoes, the problem was not the mere sting, which was as nothing, but what the sting risked leading to. If with the sting the mosquito left behind microscopic malaria parasites in the soldier’s blood, then within a week that soldier would be a physical wreck, alternating between shuddering chills and burning fever as his spleen and liver become enlarged, anaemia developed, and his skin turned yellow with jaundice. If the victim was left untreated, death was a possibility, and in the short term he could do nothing but lie there and groan. Yet, despite that risk, the unsuitable khaki shorts worn by the Diggers meant that they habitually presented plenty of vulnerable flesh.

Within a week of the militia arriving, the thin resources of Moresby’s medical personnel were desperately trying to cope with over 150 cases of bacillary dysentery. Shortly, there would be numerous cases of malaria, and yet another two hundred were so ill with various ailments that they were unable to do anything at all.

The one notable exception to this was Sam Templeton’s B Company, which remained essentially healthy because from the beginning of their training at Camp Darley, ‘Uncle Sam’ had drummed into his blokes the need for cleanliness, as a way of avoiding illness. Wash your pots and pans and plates before and after eating, tend immediately to whatever minor sores or wounds you might have before they begin to suppurate, and bloody well boil any dodgy water before drinking it. He had seen too many blokes die in the Great War for simple want of taking such basic measures, and he wasn’t about to see it happen again. One he didn’t have to tell twice was Joe Dawson, who was fastidious about personal hygiene, most particularly when it came to teeth cleaning. Joe just had a thing about cleaning his teeth after every meal, wherever they were, whatever they were doing, something not necessarily shared by other soldiers. As a matter of fact, one of the young blokes Joe had come across early in the piece—a bumpkin from the far west of Victoria—had stared in amazement at Joe’s toothbrush, and said ‘What’s that?’

In response to the health crisis, Major General Morris tended to storm around thrashing the side of his leg with his fly-whisk to indicate his extreme displeasure at how bad things were—and probably killing a few more flies in the process—but things continued to get worse all the same. One attempt to fix the flies around the latrines was to detail a platoon to pour petrol down into them, followed by a burning rag, as they ran for their lives. But this strategy was discontinued when it was decided that the flies posed less of a risk than petrol explosions, and what came with it. (If there had been a fan, it would have been hit.)