Kosher and Traditional Jewish Cooking: Authentic Recipes From a Classic Culinary Heritage: 130 Delicious Dishes Shown in 220 Stunning Photographs (39 page)

Authors: Marlena Spieler

Beef, goat and lamb, when prepared appropriately, are all permitted by the laws of Kashrut.

Though the basic principles of Kashrut are outlined in the Bible, they have been ruled upon and commented upon by rabbis in the Shulhan Aruckh, the code of Jewish law. There is no reason given for the laws of Kashrut, though many have suggested that hygiene, food safety and health might be contributory factors. The rabbis state, however, that no reason or rationale is needed; obeying the laws of Kashrut is a commandment from God.

Only certain types of meat are allowed, based on the text in Leviticus 11:3, which states: “Whatsoever parteth the hoof, and is clovenfooted, and cheweth the cud…that shall ye eat”. These conditions mean that ox, sheep, goat, hart, gazelle, roebuck, antelope and mountain sheep may be eaten. No birds or animals of prey are allowed, nor are scavengers, creeping insects or reptiles.

The Torah is not quite so clear when it comes to identifying which birds may be eaten. Instead, it lists 24 species of forbidden fowl. In general, chickens, ducks, turkeys and geese are allowed, but this can vary. Goose is popular among Ashkenazim, while Yemenite Jews consider it to be of both the land and sea and therefore forbidden.

For kosher animals to become kosher meat, they must be slaughtered ritually by

shechita

. An animal that dies of natural causes, or is killed by another animal, is forbidden. The knife for slaughter must be twice as long as the animal’s throat and extremely sharp and smooth.

The

shochet

(ritual slaughterer) must expertly sever the animal’s trachea and oesophagus without grazing its spine; any delay would bring terror to the animal and render the meat unkosher.

This is the term used to describe the removal of blood from an animal immediately after slaughter, which is essential if the meat is to be labelled kosher.

To Jews, blood is a symbol of life, and the prohibition against consuming it comes from the

scriptures: “Therefore I said unto the children of Israel, No soul of you shall eat blood…” (Leviticus 17:12).

Goose is very popular among Eastern European Jews who, in the past, often raised them for their fat livers and to serve at holiday meals.

All meat must be kashered by soaking, salting or grilling (broiling) so that no blood remains.

To be considered kosher, all fish must have detachable scales and fins. Other sea creatures that are forbidden include all shellfish and crustaceans, sea urchin, octopus and squid.

Deuteronomy states “Thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk.” This is the basis for the rule that dairy foods and meat must not be cooked together. After eating a meat meal, a certain amount of time must elapse before dairy food can be consumed. Some communities wait six hours, while others wait only two hours.

To ensure the complete separation of meat and milk, kosher kitchens have separate dishes, pans and washing-up utensils for each. These must be stored separately.

Natural rennet, the ingredient used to curdle milk for cheese-making, comes from the lining of an animal’s stomach. Therefore, the cheese made from it is not kosher. Much modern cheese is made with vegetable rennet, but not necessarily labelled as such, so to be sure, eat only cheeses that are marked “Suitable for Vegetarians”.

Because gelatine is made from animal bones, it is not kosher. Kosher gelatine made from seaweed (carrageen) is vegetarian, and must be used instead.

Pareve

foods such as barley, onions, aubergines (eggplant), tomatoes and eggs can be eaten with either meat or dairy foods.

In Yiddish, these foods are known as

pareve

and in Hebrew they are

parva

. These are the neutral foods that are neither meat nor dairy. They do not have the same restrictions imposed upon them and can be eaten with meat or dairy foods. All plant foods such as vegetables, grains and fruit are

pareve

, as are eggs and permitted fish. Jews who keep kosher will not eat

pareve

foods that have been prepared outside the home as they could have been prepared using non-kosher fats.

To be sure that any packaged food is kosher, look for a symbol of recognized certification every time you buy, as additives and methods can change. There are numerous certifying boards, and many Jews will eat only packaged foods certified by specific boards. If a food is certified as Glatt Kosher it conforms to a particularly stringent Kashrut, which requires, among other things, that the lungs be more thoroughly examined.

Some Observant Jews will eat foods such as canned tomatoes, for the only ingredients are tomatoes and salt. Others avoid such foods, as they could have been contaminated on the production line. Very strict Jews extend their watchfulness even to the basics, and will eat only sugar with the rabbinical supervision marking, to be sure it has not been tainted by other unkosher food products or insects.

In both the Ashkenazi and Sephardi kitchen, all dairy foods are held in very high esteem, a tribute to the biblical description of the land of Israel as a “land of milk and honey”.

There are strict rules concerning the consumption of dairy foods, but they do not have great religious significance except during the festival of Shavuot. This is sometimes known as the dairy festival and is a time when dairy products are enjoyed for main meals, in preference to meat, which is normally enjoyed at festivals and celebrations.

The milk taken from any kosher animal is considered kosher. Cows, goats and sheep are all milked and the milk is then drunk or made into various dairy products such as butter, yogurt and sour cream. The influences of the past can be seen in the dairy products that are still enjoyed by Jews today.

In the past, in Northern Europe, milk from cows was readily available and, because the weather was cool, spoilage was not a great problem. Many towns and villages had small dairies that produced sour cream, butter, buttermilk, cottage cheese and cream cheese, and families often owned a cow or two of their own.

In Lithuania, however, goats tended to be kept more often than cows and were referred to as Jewish cattle. In warmer countries, especially those situated around the Mediterranean, goats and sheep were much easier to raise, and their milk was more suitable for making fermented dairy products such as yogurt, feta cheese and halloumi. Today, Israel is a great producer of many different types of yogurts and sour creams.

A wide variety of kosher cheeses are produced in modern-day Israel, including kashkaval, which resembles a mild Cheddar; halloumi; Bin-Gedi, which is similar to Camembert, and Galil, which is modelled on Roquefort. Fresh goat’s cheeses are also particularly popular in Israel and are of a very good quality.

Cream cheese has been very popular with Ashkenazim since the days of

shtetlach

, where it was made in small, Jewish-owned dairies, and sold in earthenware pots or wrapped in leaves.

Soft cheeses such as cream cheese and cottage cheese were also often made in the home. Cream cheese is the classic spread for bagels, when it is known as a schmear. It can also be flavoured with other ingredients such as chopped spring onions (scallions) and smoked salmon and is widely available in supermarkets and delis.

Cottage cheese, cream cheese, feta and kashkaval are among the many kosher Jewish cheeses.

These were a great legacy of New York’s Lower East Side Jewish community. Among the most famous of the dairy deli restaurants was Ratners, known for its elderly waiters who were invariably grumpy, nosy, bossy and ultimately endearing.

Dairy shops and restaurants sold specialities such as cheese-filled blintzes, cheesecake, cream cheese shmears and knishes.

Among other treats on offer at most dairy delis were boiled potatoes with sour cream, hot or cold borscht, cheese kugels and noodles with cottage cheese.

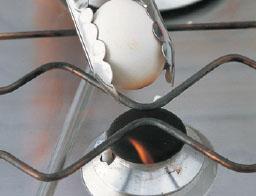

These represent the mysteries of life and death and are very important in Jewish cuisine. They are brought to a family on the birth of a child, and served after a funeral to remind the mourners that, in the midst of death, we are still embraced by life. They also represent fertility.

In some Sephardi communities, an egg will be included as part of a bride’s costume, or the young couple will be advised to step over fish roe or eat double-yolked eggs to help increase their fertility.

Eggs are

pareve

(see page 197) so may be eaten with either meat or dairy foods. They are very nutritious and filling and provide a good source of protein when other sources may be lacking or forbidden due to the strict laws of Kashrut (see pages 196–7).

These feature prominently in the Pesach Seder festival – both symbolically and as a food. It is said that a whole egg represents the strength of being a whole people (unbroken, the shell is strong; broken, it is weak).

Eggs are also an important ingredient during the festival of Pesach, as yeast, the usual traditional raising agent, may not be used for baking. Eggs, when beaten into a cake mixture (batter), can help the cake to rise.

A roasted egg is traditionally placed on the Seder plate to represent the cycle of life. It is symbolic of the ritual sacrifice made at the Temple during biblical times, and is not usually eaten.