Kosher and Traditional Jewish Cooking: Authentic Recipes From a Classic Culinary Heritage: 130 Delicious Dishes Shown in 220 Stunning Photographs (40 page)

Authors: Marlena Spieler

A hard-boiled egg is roasted over a medium gas flame, or in the oven.

This simple dish is the first thing eaten when the Pesach service is over. It is only eaten at this time.

1

Hard-boil the eggs. Meanwhile, in a small bowl, dissolve 2.5ml/

1

/

2

tsp salt in 120ml/4fl oz/

1

/

2

cup warm water. Cool, then chill.

2

Shell the eggs and serve with the salt water for dipping, or place them in the bowl of salt water.

These are a Sephardi speciality. Whole eggs are cooked slowly with onion skins or coffee grounds, to colour the shells. Alternatively, they may be added to the slow-cooked stew, dafina. They are delicious mashed with leftover cholent, in savoury pastries, or chopped and added to simmered brown broad (fava) beans with a little garlic, onion, olive oil and hot chilli sauce.

Cooking the eggs with onion skins colours the egg shells but does not impart any flavour to the egg inside.

1

Place 12 eggs in a pan and add salt and pepper. Drop in the brown outer skins from 8–10 onions, pour over water to cover and 90ml/6 tbsp oil.

2

Bring to the boil, then lower the heat to low and cook for 6 hours, adding more water, if required. Shell and serve.

Hard-boiled egg, chopped with onion and mixed with a little chicken fat or mayonnaise, is one of the oldest Jewish dishes. In modern-day Israel, an avocado is often mashed with the eggs. Scrambled eggs with browned onion and shredded smoked chicken on slices of rye toast or bagels make a perfect brunch.

For Observant Jews, meat must be kosher. Originally, any Jew versed in the ritual could slaughter meat, but this changed in the 13th century, with the appointment of

shochets

(ritual slaughterers). To qualify for this post, a man needed to be very learned, pious and upstanding.

Meat has always been an expensive but highly prized item on the Jewish table. For Ashkenazim, it was made even more costly with the levying of a hefty government tax (

korobka

). This, together with a community tax for Jewish charities, brought the price to twice that for non-kosher meat. None of this deterred Jews from eating meat, however; they simply saved it for special occasions.

Veal escalopes (US scallops) are often pounded to make the classic Viennese schnitzel.

These were favoured by the Sephardim from North Africa and other Arabic lands until the early 20th century, when the strong French influence introduced beef and veal to their table. Due to the time-consuming removal of the sciatic nerve required by the laws of Kashrut, the Ashkenazim avoided eating the hindquarters of lamb and mutton until the 15th century, when a meat shortage made the lengthy procedure worthwhile.

This is very popular, especially among European Jews. Brisket is grainy and rough textured, but yields a wonderful flavour when cooked for a long time. The same applies to the short ribs and the chuck or bola. Many of these cuts are not only excellent for pot-roasting and soups; they also make good salt or corned beef and pastrami. Beef shin makes a marvellous soup.

Both Askenazim and Sephardim use beef to make a wide array of sausages and salamis. The Ashkenazim tend to favour cured sausages such as frankfurters, knockwurst, knobblewurst and spicy dried sausages, while the Sephardim favour fresh sausages, such as the spicy merguez from North Africa and France.

This is a favourite meat for all Jewish communities, because it is so delicate and light: shoulder roast, breast of veal, shank and rib chops are all very popular cuts along with minced (ground) veal. The breast would often be stuffed, then braised with mixed vegetables; minced veal was made into cutlets and meatballs; and, in Vienna, slices of shoulder, or escalopes (US scallops), were pounded until they were very thin, then coated in breadcrumbs and fried to make the famous crisp, golden schnitzel.

Spiced or seasoned meatballs are very popular throughout the Jewish world and come in many different forms.

• Russian bitkis are made from minced (ground) beef, often with chopped onion, and may be fried, grilled (broiled) or simmered, often alongside a chicken for a Shabbat or other festive meal.

• Kotleta are flattened meatballs that are fried.

• Cylindrical Romanian mitetetlai are flavoured with garlic, often with parsley, and are fried or grilled (broiled) until brown.

• The Sephardi world has myriad meatballs: albondigas, boulettes, kefta or kofta, and yullikas. They are highly spiced and can be grilled (broiled), cooked over an open fire or simmered in sauces.

These include goat and deer (venison). Goat is popular in Sephardi cooking and is often used in dishes where lamb could be used, such as spicy stews, curries and meatballs. Venison is cooked in similar ways to beef.

Historically, poorer families tended to eat cheaper cuts of meat, such as feet, spleen, lungs, intestines, liver, tongue and brains. These were popular with both Ashkenazim and Sephardim, especially Yemenite Jews, who are still famed today for their delicious spicy offal soups.

Kosher meat is usually tough because the cuts eaten tend to contain a high proportion of muscle; the meat is not tenderized by being hung but must be butchered within 72 hours of slaughter; and because the salting of meat to remove blood produces a dry result. Because of this, meat is generally cooked very slowly by stewing, braising, pot-roasting and simmering until the meat is tender.

These long, slow methods are also ideal for the Shabbat meal, which can be prepared and cooked ahead of time, then left in the oven to grow beautifully tender.

When meat is cooked quickly, for instance in kebabs, the meat is marinated first to tenderize it. Chopping or mincing (grinding) meat has a similar effect, which is why so many Jewish meat recipes are for meatballs, patties and meat loaves. These dishes also allow a modest amount of meat to be stretched.

Each region favours certain flavourings. The Polish choose sweet-and-sour flavours; the Germans sweet and fruity ones; the Russians savoury, with onions; the Lithuanians spicy and peppery. Sephardim favour spices and fresh seasonal vegetables. Moroccans add sweet, fruity flavours to their meat; Tunisians prefer sharp spices; Turkish Jews add tomatoes and fresh herbs such as dill; while the Persians prefer delicate flavours, with fresh herbs, fruits and vegetables and also beans.

A traditional Ashkenazi dish, meatloaf is called klops. It is delicious served either hot or cold.

1

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/Gas 4. Combine 800g/1

3

/

4

lb minced (ground) meat, 2 grated onions, 5 chopped garlic cloves, 1 grated carrot, chopped parsley, 60ml/4 tbsp breadcrumbs, 45ml/3tbsp ketchup and 1 beaten egg.

2

Form into a loaf and place in a roasting pan. Spread over 60ml/4 tbsp tomato ketchup and arrange 2 sliced tomatoes on top. Sprinkle over 2–3 sliced onions.

3

Cover the pan with foil and bake for 1 hour. Remove the foil, increase the temperature to 200°C/400°F/Gas 6 and remove some of the onions. Bake for 15 minutes, or until the meat is cooked and the onions browned.

Traditionally, Jewish delis sold either meat or dairy foods. Meat delis always have a wonderful choice of cured meats and sausages – salt beef on rye, salami, smoky pastrami or frankfurters and knockwurst with sauerkraut.

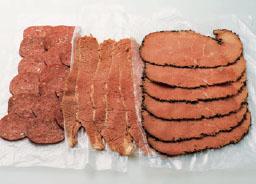

Beef salami, salt beef and spicy pastrami are classic deli fare.

This is considered meat in the laws of Kashrut, and is therefore subject to all the same rules as regards slaughter and preparation. Any part of a permitted bird can be eaten.

This is probably the most popular fowl for both Sephardim and Ashkenazim. Like beef and lamb, chicken was once reserved for the Shabbat or other festive meal. However, chicken was later served more frequently as people often raised a few chickens of their own at home and could take them to the shochet when the right time came.