Lamplighter (36 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

While the others lads washed, Rossamünd hid the pot between his bed chest and the wall under his valise and salumanticum to foil the questing chambermaids on their morning rounds.

Food gobbled (farrats, raisins and small beer) and barely more than an awkward “good morning” exchanged with Threnody, Rossamünd was rushing back to his cell, an idea illuminating in his mind like a thermistor’s bolt. He fished out the chamber pot from its hide, took out his lark-lamp, prized off the lugs and opened the top of the bell. Into the glass-bound cavity he managed to fit all five fronds, stuffing the sixth in with all the dead bloom wrapped in his smock and hiding it again in the bed chest. He filled the lark-lamp with water from the cistern and by breakfast-end had the bell-top secured back in place and the lamp safely back in his bed chest.

All through the rest of the day, he was in anxious expectation of discovery. At morning parade he waited for the Master-of-Clerks to arrive and announce the wicked theft of bloom-rubbish from beneath the Scaffold.Through morning evolutions Rossamünd kept looking guiltily over at the gaunt tree, convinced a mercer would run up and announce that “some unknown miscreant had meddled with the rightfully exposed collucia plants!”

None of this happened.

By middens, Rossamünd was eager to restore the rescued glimbloom to Numps.

The glimner was still in bed, sitting up, sipping at some fine-smelling broth—probably a kindness of Doctor Crispus—and looking utterly spent from all his grieving. Gratified the man was cared for, nevertheless Rossamünd felt his heart ache to see Numps so woebegone.

“Mister Numps,” Rossamünd ventured, “I—I tried to save your bloom yesternight, but . . . but this was all I could get. The rest was too high off the ground.” He proffered the bloom-packed lark-lamp and the glimner’s eyes went so round Rossamünd feared they might pop right from their sockets. For a terrible beat or three of his anxious heart, the prentice thought he had woefully miscalculated, and simply added to the glimner’s distress.

“You rescued poor Numps’ poor friends,” the man managed brokenly. He took the small lamp in shaking hands and gradually his hauntedness gave way to profound delight as joy blossomed into ecstasy. “Oh, my friends!” Numps cried, in both shouts and tears. “Oh, my friends!” The unscarred side of his face became wet with weeping, yet the riven side stayed dry, his ruined eye tearless.

19

BILLETING DAY

fetchman

also fetcher, bag-and-bones man, ashcarter or thew-thief (“strength-stealer”). Someone who carries the bodies of the fallen from the field of battle, taking them to the manouvra—or field hospital. Despite their necessary and extremely helpful labors, fetchmen are often resented by pediteers as somehow responsible for the deaths of the wounded comrades they take who often die later of their injuries. Indeed, they are regarded as harbingers of death, sapping their own side of strength, and as such are kept out of sight till they are needed.

also fetcher, bag-and-bones man, ashcarter or thew-thief (“strength-stealer”). Someone who carries the bodies of the fallen from the field of battle, taking them to the manouvra—or field hospital. Despite their necessary and extremely helpful labors, fetchmen are often resented by pediteers as somehow responsible for the deaths of the wounded comrades they take who often die later of their injuries. Indeed, they are regarded as harbingers of death, sapping their own side of strength, and as such are kept out of sight till they are needed.

D

ESPITE the dramatic events, many of the lantern-sticks were largely unperturbed by the Marshal’s departure. Grindrod and Benedict did their utmost to preserve the routine.The next day the prentices had just completed the usual afternoon reading on Our Mandate and Matter with Seltzerman Humbert when Benedict hustled into the lectury declaring in amazement, “They’re holding Billeting Day early!”

ESPITE the dramatic events, many of the lantern-sticks were largely unperturbed by the Marshal’s departure. Grindrod and Benedict did their utmost to preserve the routine.The next day the prentices had just completed the usual afternoon reading on Our Mandate and Matter with Seltzerman Humbert when Benedict hustled into the lectury declaring in amazement, “They’re holding Billeting Day early!”

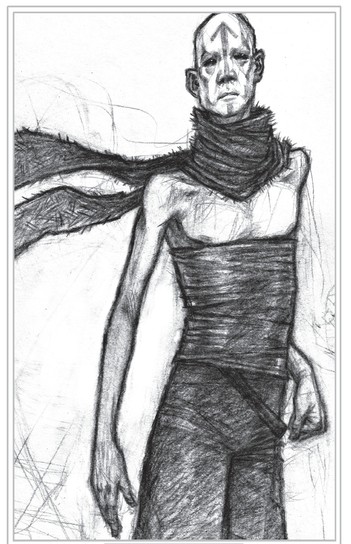

Almost the moment these words were out, the grandiose figure of the Master-of-Clerks, the Marshal-Subrogat himself, appeared at the lectury door, gracing them all with his presence. He held his chin at a dignified tilt. As always, the man was served by his ubiquitous retinue: Laudibus Pile; Witherscrawl, and now Fleugh the under-clerk; the master-surveyor with diagrams of the manse permanently gripped under his arm; and two troubardier foot-guards.With them also came a lanky, frightening-looking fellow dressed all in lustrous black: heavy boots, black galliskins over tight leggings, black satin longshanks. His trunk was swathed in a sash of sturdy proofed silk, neck thickly wrapped in a long woolen scarf yet—most oddly—his chest and shoulders and arms were bare, despite the aching chill, showing too-pale against all the black. His head was bald, and a thin dark arrow pointed up his face from chin to absent hairline, its tines splaying out over each brow. He was a wit. More disconcerting still was that his eyes were completely black—no white orbs, just glistening dark.This was some strange trick of chemistry Rossamünd had not heard of.The combination of this blank, pitch-dark stare with Pile’s snide, parti-hued gaze stilled the whole room as they moved within.

With a thump of determined footfalls Grindrod appeared behind them all, muttering to himself, his face screwed up in silent invective. “Sit” was all he said.

The prentices obeyed with meek alacrity.When all shuffling and snuffling ceased, the Master-of-Clerks paced before them, hands behind his back, puckering his lips and squinting at the platoon as if shrewdly appraising them all.

“Brave prentices,” he declaimed, “you have worked at your practicing with admirable zeal and laudable facility. Fully confident in your fitness, I am convinced you are ready for full, glorious service as Emperor’s lighters, and have decided it timely for you to be granted your billets and to be sent promptly to them.”

THE BLACK-EYED WIT

That had most of the prentices scratching their heads, pained frowns of lugubrious thought creasing several brows.

Does that mean it’s Billeting Day or what?

Does that mean it’s Billeting Day or what?

How would he know what the state of our fitness for service is?

was the spin of Rossamünd’s own thinking.

He has naught to do with us!

was the spin of Rossamünd’s own thinking.

He has naught to do with us!

With a harsh, self-conscious throat-clearing, Grindrod stood forward, clearly struggling to contain his temper. “Sounds an admirable conclusion, sir, but the lantern-sticks bain’t ready for the work. Ye let a half-trained lad out on the road by himself and ye might as well toss ’im straight to the fetchman!”

“Pshaw! I’ll not have your womanish obstructions, Lamplighter-Sergeant-of-Prentices.” The Master-of-Clerks enunciated Grindrod’s full title in the manner of a put-down. “They are required out on that road to make up for the appalling losses incurred under my predecessor.”

The Lamplighter-Sergeant went purple with indignant rage, but the Master-of-Clerks carried on, not allowing the man an opportunity to press any further dissent.

“Staffing at the cothouses must be restocked. We have twenty-one—no, twenty-two”—he corrected himself with an enigmatic look to Threnody, sitting straightbacked at the front of the room—“hale souls trained in the lampsman’s labors, and as ready as anyone can be, surely, to wind a simple glowing weed in and out its chamber. It is a terrible waste of a resource and one I have decided can be better employed filling these gaps on the road than lolling about here being taught the same thing over and over. It is not difficult work, Sergeant. If they have not come to grips with the task by now, I fail to see how another month will make it so.”

“Another month is all the difference, sir!” Grindrod glowered. “They’re bare-breeched bantlings who set to whimperin’ at the slightest speak of bogles! Ye should be hiring those blighted sell-swords bivouacked outside the Nook, or get them lardy magnates in the Placidine itself to spare a platoon or two of their blighted domesticars! Either way, sir, trained, professional men-at-arms used to the rigors of war. Ye might not know, sir, hidin’ behind yer ledgers and quill pots, that it’s war out upon the road, sir, and it’s we lowly lighters who are in the van!”

The Master-of-Clerks bridled for a moment and then, with admirable equanimity, said soothingly, “I’m sure you’re a fellow who knows his business well enough when teaching a poor lad his first clues, but it now falls to me to choose their best uses. That is to be the end of it, Lamplighter-Sergeant—I do not want to be put in the position of having to take you in firmer hand. Indexer Witherscrawl,” he said, dismissing Grindrod with a turn of his gorgeously bewigged head, “read the tally if you please.”

The sour indexer stepped forward, glared at the prentices—at every single one—and especially at Threnody. “Harkee, ye little scrubs! Here is the Roll of Billets, of who will go to where and when they will leave. Listen well—I shall tell this only the once!”

What!

The prentices could not quite believe this: they were to be denied the full honors of a beautiful and especial ceremony. There were supposed to be martial musics; the whole manse was meant to turn out in respect at the boys’ success in prenticing and their coming into full rank as lampsmen. A susurrus of deep displeasure stirred about the boys.

The prentices could not quite believe this: they were to be denied the full honors of a beautiful and especial ceremony. There were supposed to be martial musics; the whole manse was meant to turn out in respect at the boys’ success in prenticing and their coming into full rank as lampsmen. A susurrus of deep displeasure stirred about the boys.

Grindrod did nothing to quell them, simply folding his arms. In fact, he showed open pride in the prentices’ muttering rebellion.

“I said, quiet!”

Witherscrawl shouted, and a foot-guard rapped the floor with the shaft end of his poleax, its cracking report startling the whole room to dumbness.

Witherscrawl shouted, and a foot-guard rapped the floor with the shaft end of his poleax, its cracking report startling the whole room to dumbness.

With a foul sneer, the indexer raised a tall, thin ledger close to his face and from it began to read out names in letter-fall order: Arabis to go to Cothallow, Childebert to Sparrowstall, Egadis to Tumblesloe Cot just beyond the Roughmarch, and so on.

Attention focused.

“Mole to Ashenstall . . .”

Onion Mole went white with dismay.The other prentices winced, Rossamünd with them. A long way east, Ashenstall was one of the harder billets on the road, isolated and with few vigil-day rests.

Apprehension grew. They could not assume only the kinder billets would be given.

“Wheede to Mirthalt . . . ,” droned the indexer, “Wrangle to . . . Bitterbolt . . .”

With a chill, Rossamünd knew his name was next, languishing at the end of the lists along with Threnody’s . . .

“Bookchild to Wormstool . . .”

. . . and this chill became a frigid blank.

Some of the other prentices gasped.

Wormstool!

This was the last—the very last—cothouse on the Wormway, well east of Ashenstall, with only the grim Imperial bastion of Haltmire between it and the Ichormeer. Built at the “ignoble end of the road,” Wormstool was no place for newly promoted prentice-lampsmen. Situated too near the sodden fringe of the dread swamp, it was held as one of the toughest billets of all. Only those who volunteered ever went there, yet here he was, a mere prentice, being

sent

. The Ichormeer had once been just a frightful fable to him. Now Rossamünd was going to live and work as a neighbor to its very borders, where all the bogles and the vilest hugger-muggers that ever dragged themselves from putrid mud haunted and harried. Absorbed in his shocked thoughts at this revelation, he did not hear where Threnody had been sent.

sent

. The Ichormeer had once been just a frightful fable to him. Now Rossamünd was going to live and work as a neighbor to its very borders, where all the bogles and the vilest hugger-muggers that ever dragged themselves from putrid mud haunted and harried. Absorbed in his shocked thoughts at this revelation, he did not hear where Threnody had been sent.

Witherscrawl finished his recitation.

The Master-of-Clerks presented himself again. “I will be wanting you all to your billets as soon as can be done. With time to travel in consideration, those farther out will leave sooner. Therefore those prentices stationed farthest away will be leaving on the first post of tomorrow morn. Well done to you all, my fine fellows—you are now all full lampsmen!”

Confused and silent, the prentices were dismissed and that was that: Billeting Day—such as it had been—was over, an insulting sham.

The Master-of-Clerks left without any further acknowledgment, taking his “tail” with him. Grindrod followed, and an angry, muttered conference could be heard out in the hallway, terminating suddenly with the Master-of-Clerks’ high clear voice saying, “Cease your querulous bickerings, Sergeant-lighter! It will be as I have decided it. They have been sent where needed. If you are so concerned for the children, then get back to them and make certain they are ready for their great adventure. Good day!”

At first Rossamünd’s fellows were bemused. As the day progressed most were reconciled with their early promotions and many proved pleased with their billets, however untimely and however tawdrily they had been portioned. At lale—held indoors owing to inclement weather—they buzzed and boasted excitedly to each other about the various merits of their new posts, those billeted at the same cothouse gathering together in excited twos or threes. Every lad congratulated the others for their good fortune and the 7q extra they would all receive each month now that they were lampsmen 3rd class. For Onion Mole and even more so for Rossamünd there was baffled commiseration: he was the only prentice to be billeted at the ignoble end of the road.

Other books

Wicked by Shannon Drake

Knitting in the City 01 Neanderthal Seeks Human by Penny Reid

Poisoned Ground by Sandra Parshall

Glory on Mars by Kate Rauner

The Sexopaths by Beckham, Bruce

Son of the Morning by Linda Howard

A Solitary Blue by Cynthia Voigt

Black Girls and Bad Boys: Stealing Loretta by Neneh J. Gordon

Great mischief by Pinckney, Josephine, 1895-1957

The Billionaire's Promise (An Heir At Any Price Book 3) by Holly Rayner