Lamplighter (39 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

Gloaming finally gave up to darkness as they followed the glittering chain of new-lit lamps and arrived at the cothouse itself. Dovecote Bolt was a high-house: whitewashed walls upon exposed stone foundations, with a fortified stairway to the only door at the very top of the structure, a high wall extending behind it and a crowd of glowing lanterns at its front. It was built close by a sludgy ford over the beginnings of a little stream known as the Mirthlbrook. Just before the ford the post-lentum turned, went through a heavy gate and halted in the modest coach yard at the rear of the cothouse.

The splasher boy opened the door, unfolded the step and said with a parched croak, “First stop. And an overnight stay till tomorrow’s post.”

As luggage was retrieved, lampsmen appeared from within bearing bright-limns to light their way and dour expressions to greet them. The seven-strong garrison of this modest cothouse seemed very tight, veterans with a long record of service together. However, they had little cheer for new-promoted lampsmen, looking especially hard at Threnody as she mounted the stair and entered the guardroom. It occupied the entirety of that floor, and with benches and trestles, doubled as a common room for meals. The two young lamplighters were directed to the cramped office of Dovecote Bolt’s house-major, found in an attic-space loft of the steep roof.

Introducing himself as Major-of-House Wombwell, he spoke to them in a stiff yet welcoming manner.

“Good evening to you, young . . . er—prentices!” he said, eyeing Threnody with a confounded expression. His eyes became wider as he saw the small spoor upon her face. “Why have you come to us from our glorious manse? Wellnigh is the usual range of your watch, is it not?”

“Ah,” said Rossamünd, “we are on the way to our billet, sir.”

“To your billet?” The house-major bridled. “Preposterous! Billeting Day is not for another month.”

“It has been called early by our dear new Marshal-Subrogat,” Threnody explained with affected amusement.

“Marshal-Subrogat?” the man quizzed her.

“Aye, sir,” Rossamünd answered, getting a word in before Threnody for fear of some rash statement from her. “The Master-of-Clerks has filled the place of the Lamplighter-Marshal.”

“So it is true, then: the Lamplighter-Marshal is called away and that old fox Podious is top of the heap. They even let lasses serve as lighters now, I see—troublesome times are here . . .”

The house-major asked them some further questions on minor details of Winstermill’s running and then they were dismissed.Threnody, much to the bemusement of the lighters, was granted access to the kitchens to make her plaudamentum.

“Blighted Cathar’s baskets as lighters—by my knotted bowels, who’d reckon it?” Rossamünd could hear the house-major mutter as they left him.

“Would you need help with your treacle, Threnody?” Rossamünd offered as they were shown down to their cots by the cot-warden: a surly, scabby-faced lighter—one of the permanent house-watch, too old now to walk the highroad.

The girl paused, contriving to look bemused, amazed and annoyed all at once. “No thank you, I will boil my own,” she huffed, and left him to find the kitchen.

When she returned, they were served mains by the same surly cot-warden now acting as kitchen hand. Incongruously the meal of boiled beef, onions and rice from the tiny kitchen tasted better than anything made by Winstermill’s vast cookery.

Left well alone on their cots by the lampsmen,Threnody read as Rossamünd contended with a bout of the blackest sorrow.

When the lamp-watch arrived from Sallowstall, their thumping and calling reverberating through the boards above, Threnody made trouble by asking for a privacy screen. Churlishly, the old cot-warden and two of the lighters answered her demand, setting a dusty old screen for her with much ungracious puffing and banging and stomping. Finished, the cot-warden left them, muttering grumpily, “Anything else yer highness wants doing . . .” Behind the screen, by golden lantern-light, Threnody did those mysterious things girls did before going abed. When she was done, she pushed the screen away and got into her rough cot. She was in a voluminous white nightdress, her hair gathered and hidden beneath a sacklike, ribbon-tied crinickle. Rossamünd had never seen her in this way. She had been careful never to show herself after douse-lanterns back at Winstermill. The nightclothes and hat made her look curiously vulnerable. He prepared for sleep more publicly, his wounded head throbbing as it had not done for some days.

Sleep was hard-won that night. Rossamünd wrestled with his troubles as he lay in the cold listening to Threnody’s easy breathing.

Fed a hasty breakfast the next morning, they were allowed barely enough time for brewing Threnody’s treacle. A slap of reins and a shout, and the lentum went on, the weird song of unseen birds echoing across the foggy valley their only farewell. Feeling empty and exhausted, Rossamünd bid the Bolt a silent good-bye. Threnody slid over to Rossamünd’s side of the carriage and, pulling back the drape, stared at the low northward hills where Herbroulesse was hidden, still dark despite the morning glow. “Till anon, Mother,” she murmured, and kept her vigil till they were well past the cothouse and the lesser road too.

The day’s journey took them past dousing lampsmen returning to Sallowstall and on to that place itself, the quality of the road improving from hard-packed clay and soil to flagstones. With a blare of the horn, the post-lentum stopped at Sallowstall, a well-tended cot-rent with broad grounds and thick walls.

The mail was passed over and horses changed. Over the ford, scattering half-tame ducks, and out of the thicket of trees, the lentum resumed the journey.

As the afternoon wore on, the pastures on either side of the Wormway became neater, their boundaries clearer, their furrows straighter, less weedy. Much of the land was a dark, fertile brown. This was a very different land from the grayer soils of the crofts Rossamünd had known about Boschenberg. Nearing Cothallow they saw peoneers levering at the road with iron-crows while a grim-looking guard of haubardiers stood watch.

“Thrice-blighted baskets have taken to tearing up the highroad,” Rossamünd heard someone call to their driver as the post-lentum cautiously passed along. Flagstones had been torn up and thrown aside, and a great-lamp bent over like a wind-broken sapling, its glass smashed, the precious bloom torn into shreds and yellowing.

Nestled in a wooded valley, Cothallow was long and low, its thick granite façade perforated with solid arches from the midst of which slit windows stared, closely barred and ready to be employed as loopholes.Their stay was not much more than a shouted “Hallo!,” an exchange of mail and a hurried change of horses. The lenterman was clearly keen, with the advance of day, to be at the next destination.

A sparrow alighted suddenly on the lowered door sash and, ruffling its wings, inspected first Threnody then Rossamünd with keen deliberation. Threnody peered at the impertinent little bird over the top of her duodecimo. It trilled at Rossamünd once and loudly, and then shot off with a hum of speedy wings as the post-lentum jerked forward to resume its travels.

“I’ve never known such birds to be so persistent,” Threnody exclaimed. “He looks just the same as that one watching while we talked in the greens-garden by the manse.”

Rossamünd leaned forward. “Perhaps the Duke of Sparrows is watching

us

?” he whispered.

us

?” he whispered.

“I can’t think why he would watch after us particularly,” the girl answered with a frown.

“Maybe he’s making sure you don’t go witting the wrong bogle,” Rossamünd muttered with a weak grin, feeling anything but funny.

“Is there such a thing?” Threnody said seriously, looking at him sharply.

Rossamünd very much wanted to say “yes” but held his tongue.

The crowns of the hills about were thick with trees, but their flanks were broad with deep green pastures, thin breaks of lithely myrtles. Here cattle lowed and chewed and drank from the runnels that wore creases down the hillsides. Crows cawed to each other across the valley.

Their day’s-end destination was the community of Makepeace, built amid sparse, elegant, evergreen myrtles, right on the banks of the Mirthlbrook. It was the first significant settlement upon the Conduit Vermis, a village sequestered behind a massive, foreboding wall. Rossamünd could see the top bristling with sharp iron studs and shards of broken crockery, which seemed to make a lie of the Makepeace’s friendly name. Crowds of chimneys stretched well above the beetling fortifications, each one drizzling steamy smoke into the still, damp air, showing a promise of a warm hearth and even warmer food. Rossamünd imagined every home filled with humble families—father, mother, son, daughter—living quietly useful lives.

Upon either side of the gate were two doughty bastion-towers, both showing the muzzle of a great-gun through enlarged loopholes. Situated immediately by the northern tower, the cothouse of Makepeace Stile merged its foundations with those of the wall. A high fastness much like Dovecote Bolt yet greatly enlarged—maybe five or six stories—the Stile was near as tall as the chimney stacks of Makepeace and must have dominated the view of the west from within the village.

The post-lentum eased into a siding between the cothouse and the highroad, its arrival coincident with the departure of the lamp-watch.

Alighting from the carriage, Rossamünd heard a cry sound from down the gloomy road.

“The hedgeman comes! Be a-ready to make your orders, the hedgeman comes!”

It was uttered by a portly figure pulling his test-barrow and strolling toward the town from the same direction the lentum had just come, as if there was no threat from monsters.

“The hedgeman comes! Be a-ready to make your orders, the hedgeman comes!”

It was uttered by a portly figure pulling his test-barrow and strolling toward the town from the same direction the lentum had just come, as if there was no threat from monsters.

A hedgeman!

Rossamünd’s attention pricked. These were wandering folk, part skold, dispensurist and ossatomist who cured chills and set bones (for a fee) where other habilists would not venture. He had not noticed them passing the fellow earlier, though they must have.

Rossamünd’s attention pricked. These were wandering folk, part skold, dispensurist and ossatomist who cured chills and set bones (for a fee) where other habilists would not venture. He had not noticed them passing the fellow earlier, though they must have.

“The hedgeman is here! Come a-make your orders, the hedgeman is here!” came the cry again, and this time Rossamünd recognized the crier.

Mister Critchitichiello!

Mister Critchitichiello, who made his living hawking his skills to all and any along the Wormway. When he had first arrived at Winstermill, Rossamünd found it much easier to ask the kindly hedgeman to make Craumpalin’s Exstinker than go to Messrs. Volitus or Obbolute, the manse’s own script-grinders. Now, with the current batch near its end, and more required to last him at his new billeting, Rossamünd hurried over to the man through traffic and the rain.

Mister Critchitichiello, who made his living hawking his skills to all and any along the Wormway. When he had first arrived at Winstermill, Rossamünd found it much easier to ask the kindly hedgeman to make Craumpalin’s Exstinker than go to Messrs. Volitus or Obbolute, the manse’s own script-grinders. Now, with the current batch near its end, and more required to last him at his new billeting, Rossamünd hurried over to the man through traffic and the rain.

In the manse the hedgeman was a popular fellow. Rossamünd had to wait his turn while the small crowd of brother-lighters ordered eagerly. Mostly they came for love-pomades made to secure the affections of Jane Public and the other dolly-mops—the maids and professional girls living in the towns about—or find a cure for the various aches and grumbles your average lampsman seemed always to possess. Out here, however, two days east of Winstermill, Rossamünd was the only customer.

“Well ’ello there, young a-fellow.” Critchitichiello greeted Rossamünd in his strange Sevillian accent, grinning at him from beneath the wide brim of his round hat. “I a-remember you from the fortress.Yes? Back then you wore a hat and not a bandage.”

The prentice nodded cheerily.

“Hallo, Mister Critchitichiello. Triple the quantity of my Exstinker, please. I have the list for it if you need to remember its parts.”

Critchitichiello smiled. “No—no, I remember. Old Critchitichiello never forgets such clever mixings.” He tapped his pock-scarred brow knowingly. “I’ll have it ready for you in a puff, Rossamündo. You see! I even remember your name though we meet but once.”

Rossamünd followed the hedgeman as he set his test-barrow down under the eave of a small stall built against the eastern wall. A remarkable little black-iron chimney poked out and up from the back, puffing clean little puffs of smoke. Critchitichiello unlatched and unfolded his barrow, the lid swinging up to provide a roof from the rain.

Master Craumpalin would want to see this!

Rossamünd thought sadly of the charcoal ruin that Master Craumpalin’s own marvelous test had become. He gripped the list of parts made by the dispensurist’s own hand as if it were a precious jewel. He had read the recipe many times and knew it well: mabrigond, wine-of-Sellry, nihillis, dust-of-carum, benthamyn. As he observed the testing—as making a script is called—Rossamünd habitually ran through the steps in his mind.

Start with five parts—no! Fifteen parts wine-of-Sellry in a porcelain beaker over gentle heat.

Rossamünd thought sadly of the charcoal ruin that Master Craumpalin’s own marvelous test had become. He gripped the list of parts made by the dispensurist’s own hand as if it were a precious jewel. He had read the recipe many times and knew it well: mabrigond, wine-of-Sellry, nihillis, dust-of-carum, benthamyn. As he observed the testing—as making a script is called—Rossamünd habitually ran through the steps in his mind.

Start with five parts—no! Fifteen parts wine-of-Sellry in a porcelain beaker over gentle heat.

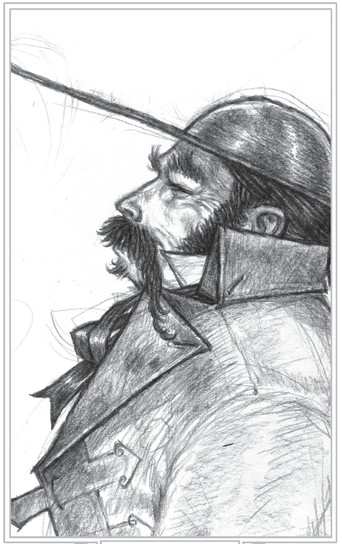

CRITCHITICHIELLO

A familiar savory smell wafted, like fine vegetable soup, as the liquid began to simmer.

Add one—ah, three parts nihillis and . . .

Pumping at an ingenious little foot bellows connected to the test-barrow, the hedgeman looked up from his work, and with a frown of friendly concern said, “You know, Rossamündo, I have a-made many nullodors along these many roads, but with this a-one here I cannot figure how it might a-do its job.” Critchitichiello shrugged, thick-gloved hands raised palms-to-the-sky.

Other books

Flat Lake in Winter by Joseph T. Klempner

Giving In: The Sandy Cove Series (Book 1) by Joseph, M.R.

Burning Hunger by Tory Richards

The Commander's Slave by K. S. Augustin

A Death Left Hanging by Sally Spencer

Midnight is a Lonely Place by Barbara Erskine

A Curious Affair by Melanie Jackson

The World We Found by Thrity Umrigar

Deep Water by Pamela Freeman

The Chocolate Lovers' Diet by Carole Matthews