Language Arts (33 page)

Authors: Stephanie Kallos

Alison inhaled sharply, as if she were about to deliver some stinging retort. Instead, she bowed her head and stopped her mouth with the back of her hand.

“You promised,” she repeated softly, and then she stood, gathered her things, and headed away.

“I prefer written correspondence to dramatic exits!” Charles shouted at her back.

He took out his pen and inscribed a short sentence on his cocktail napkin.

Then he signaled the waiter to bring him another glass of wine.

PART THREE

I dreamed I had a child, and even in the dream I saw it was my life, and it was an idiot, and I ran away. But it always crept onto my lap again, clutched at my clothes. Until I thought, if I could kiss it, whatever in it was my own, perhaps I could sleep. And I bent to its broken face, and it was horrible . . . but I kissed it. I think one must finally take one's life in one's arms.

âArthur Miller,

After the Fall

You have asked for and been given enough wordsâit is now time to live them.

âMeher Baba

Have you ever tracked the progress of your handwriting over the course of your life? If you have access to personal archival writings, you might consider making a study of the way your penmanship has evolved over the years; it can be an interesting undertaking, very revelatory.

In an opinion I share with my father, not nearly enough credence is given to graphology as a supplementary tool in the study of personal development. I think there's an argument to be made that, for those seeking degrees in psychology or psychiatry, required course work should include a class in graphology; how much those students could enhance their understanding by looking at that most direct and revealing expression of the self.

Among the books in my father's library related to this subject is one he especially likes because of its chapter on presidential penmanship. Richard Nixon's mental decline, Abraham Lincoln's melancholiaâall are clearly demonstrated. Even a novice would be able to sense a sickening, a shift.

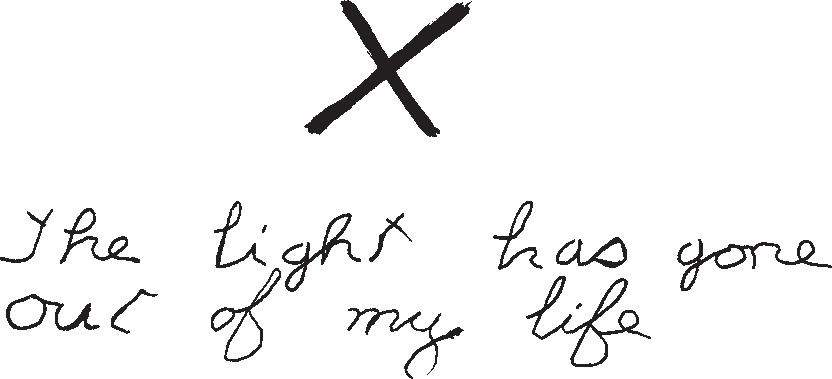

On Thursday, February 14, 1884, the day his wife, Alice, died, Teddy Roosevelt's diary entry reads as follows:

The script is quavering, the lines broken, the penman too weak to add a period.

If great men are not immune to the effects of personality on penmanship, then surely neither are the rest of us.

It was nearly time for Charles's senior-project assessment meeting (SPAM) with Pam Hamilton and Romy Bertleson, their last before the school holiday known as midwinter break; an unfortunate title, conjuring (as it did for Charles, anyway) that nineteenth-century hymn “In the Bleak Midwinter,” with its mellifluous but woeful lyrics:

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow . . .

In Seattle, rain was falling, rain on rain . . .

Charles filled the electric kettle with water in case Pam wanted some tea. Outside, another weather systemâone that had been drenching the city for daysâseemed expressly designed to authenticate Al Gore's dire hypotheses about the effects of global warming.

At this vitamin Dâdeprived point in the life cycle of Seattle's citizenry, almost everyone who didn't have the good sense to invest in a full-spectrum light-therapy system was stumbling around in a stupor of depression, lethargy, mental cloudiness, and unfulfilled expectations. Charles found that, more than at any other time of year, late January through March was when it was most difficult to avoid feeling as though he had let everyone down. The relentlessly gray, damp outer world revealed the projected truth of one's innermost character flaws, an irremediable structural rot that was the deserved result of being foolish enough to seat one's support beams in soggy ground instead of dry concrete.

Many folks took heart at this time of year in the emergence of daffodils and crocuses, grape hyacinths and snowdrops; to Charles, they were accusatory, shaming reminders of neglect. Years ago, he and Alison had planted all kinds of early-flowering bulbs. Charles knew that there was a point at which he was supposed to dig them up and separate them, but he could never remember when that was, and by the time he did remember, they'd already pushed out of the ground and were huddled together in overcrowded clumps, like tenement families, smacking their yellow- and purple- and white-bonneted heads against one another in the wind with such ferocity that their blooms survived only a couple of days.

Even City Prana's most stalwart, reliable, and rain-proof students seemed to languish. Creative-writing assignments were filled with phrases like

weeping trees

and

lachrymose moss.

Many students and their familiesâyounger versions of that special class of retirees known as

snowbirds

âfled the Pacific Northwest for an infusion of sun. Some of Charles's colleagues migrated as well.

Pam Hamilton, for example; some years she visited one of her far-flung brood of children and grandchildren; other times she attended the Cowboy Poetry Festival in Elko, Nevada, doing a lot of plein-air sketching and returning with emerging freckles and sketchbooks filled with vividly colored drawings of horses, mountains, and desert plants.

She'd given Cody one of these drawings years agoâa herd of amethyst-colored wild mustangs, grazing and becalmed before the backdrop of a fantastically colored western sky. Cody couldn't stop staring at it when Charles brought him into Pam's art room once for a visit, so she'd had it framed and given it to him when they moved him into his first group home. The picture hung in his bedroom there, and in the three subsequent bedrooms he'd occupied since then, four homes in ten years, a visual touchstone through all the upheavals that Alison felt compelled to put Cody throughâalways with the best of intentions, always with the hope that the next situation would be better.

None of Cody's homes were

bad

in the sense of being unfit, abusive, or criminal, thank God; never did they have to move him because they were faced with one of the worst-case scenarios featured in those newspaper exposés Charles was always finding.

What drove Ali, what she really hoped, of course, was that

Cody

would be better, that these perennial change-ups in environment and personnel would spark some transformation. They never did. Cody, like those wild purple ponies, remained fixed, static, as if he too were held within a mitered wooden frame.

Charles wondered what Pam was doing over midwinter break this year.

His plans mostly involved helping Alison and the Young/Gurnees ready the house for the boys' moving-in day, which was set for mid-April.

Beyond that, he'd be grading papers and watching DVDs of films that took place in sun-drenched settings. It was the perfect time of year to revisit those Merchant Ivory adaptations, stories in which repressed, tightly wound Englishmen traveled to the Italian countryside, shed their inhibitions and their waistcoats, and magically transformed into skinny-dipping, freewheeling hedonists.

â¢â¦â¢

“There's this new movement called photolanthropy,” Romy was saying, “photography that draws attention to a cause or an issue . . .”

You mean photojournalism,

Charles almost said, but he stopped himself;

photolanthropy

was a catchy word, one that would certainly be a dashing addition to the common-usage dictionary.

“You have to make yourself invisible, let the camera do the work,” Romy continued.

“What happened to that woman you were having trouble with?” Pam asked.

“Mrs. D'Amati? Oh, I thought I already told you. She and . . .”âRomy darted her eyes to Charlesâ“another artist have started to collaborate. I'm hoping to get a portrait of the two of them working together. It just hasn't happened yet.”

“Well, you've already got a lot of terrific images to choose from,” Pam said. “As far as I can tell, you're right on track.” She glanced at Charles. “How is the written component of the project coming together?”

“I'm still planning on writing American Sentence captions for the photos . . .”

Charles knew he was being distant, preoccupied, not at his senior-project-adviser best, essentially forcing Pam to conduct the meeting without his help. But in his own defense, he was acting as adviser on

seven

other senior projects this year, a record number. Surely it wasn't a sin to coast a bit on this particular occasion. Pam was the one who'd suggested they do this as a team, after all. She was the one who'd said co-advising would allow them to

share the load.

He needed someone to share the load right now. It had finally dawned on him just what he had signed up for in the next ten days: a remodeling assault on Perfect Pinehurst.

The magnitude of what lay aheadâMerchant Ivory films notwithstandingâsuddenly fell on him like a circus tent collapsing under the weight of a monsoon.

“Yes. Right on track,” he blurted, sweeping Romy's paperwork into a pile and thrusting it in her direction.

Pam and Romy stared at him. Charles realized that he'd not been following their conversation and had perhaps spoken inappropriately. A compliment was in order.

“You're very gifted, Romy,” he said.

“Oh, I don't think it's me,” she replied. “There's something Diane Arbus said, about how having this thing”âshe indicated her camera, which was positioned, as usual, at the center of her chestâ“gives you an advantage. She said, âIt's like you're carrying some slight magic.'”

Romy smiled, radiantly.

Charles's breath grew suddenly shallow; he found himself staring. Romy's use of the word

magic

âunusual in this settingâalong with the measured, mature emphasis she'd used when speaking the quote, her satsuma aura, and the fact that she

so

resembled Emmy had the unexpected and embarrassing effect of bringing tears to his eyes.

“Will you excuse me?” he said, abruptly taking up his school satchel and flimsy umbrella and heading for the door. “I completely forgot that I have an appointment. Please, if you don't mind, finish up without me, and then, Ms. Hamilton, could you lock up when you're done?” He left without waiting for a reply.

â¢â¦â¢

Language Arts class did not prove to be the earthshattering experience Charles expected, although it was fundamentally different from the rest of the school day in at least one way:

Before lunch that first day, ten

exceptional

children trooped to the libraryâno hall passes requiredâand joined Mrs. Braxton, who was already seated, not behind a desk but in one of eleven chairs that were arranged in a

circle,

each chair seat containing a pristine copy of

Language Arts: A New Approach to Discovering the Joys of Reading and the Elements of Creative Writing.

Mrs. Braxton did not direct the arriving students to any particular place; they could sit, she said, wherever they wanted.

Initially, Charles found this egalitarian setup and radical freedom distressing. There was nowhere to hide from either Mrs. Braxton or his fellow classmates; he'd had quite enough of center stage at this point and had begun to feel nostalgic for his era of academic invisibility. He had other concerns as well: Were they supposed to sit somewhere different every day? Was the place each chose to sit some kind of a test?

For the first week, these questions filled him with anxiety. If being chosen for Language Arts was supposed to be some kind of

honor,

he'd rather do without.

As time passed, however, and it became clear that most children preferred to occupy the same seat day after day (especially Astrida, who consistently rushed to station herself at Mrs. Braxton's side) and weren't penalized for it, he relaxed, grateful for the fact that, given this configuration,

everyone

was in the front row,

everyone

was noticed. In a sense,

everyone

was a teacher's pet.