Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

Last Days of the Bus Club (14 page)

‘Er … yes.’

‘You live down there at El Valero, don’t you? I know all about you. She flapped her housecoat. ‘Now, what seems to be the problem?’

‘It’s my … er …’ and I indicated my crotch.

‘Alright, then,’ she said. ‘Out with the

culebrina

and let’s have a look.’ (A

culebrina

is a little serpent.)

This was it. I fumbled with the buttons of my fly, then bent over and reached in, gingerly coaxing the timid little creature from its lair for inspection. The

curandera

peered at it, aghast. It was not looking its best.

‘It’s a nice colour,’ she observed after a bit. ‘Don’t you worry … we’ll fix it up in no time.’ And so saying, she sprinkled some talcum powder on the affected part, and set to rubbing it with a gentle circular motion.

This was far from unpleasant – in fact it felt really rather nice. I strove to think about something disagreeable in order to discourage any untoward tumescence. But try as I might, the thoughts wouldn’t come. It was too nice a day: there was a beautiful low winter sun; I had enjoyed a long walk accompanied by joyful dogs to a lovely Alpujarran village; my penis was being rhythmically rubbed; and soon I would be walking back to a blazing fire and a delicious supper in the company of family and friends. I could feel blood creeping ominously about my body, looking for some empty space to fill, some erectile tissue perhaps, to make turgid … and turgid was the last thing I needed right now.

The

curandera

meanwhile was still rubbing. So I struggled to think of something dull and dispiriting. This of course is a tried and tested sexual technique; instead of meditating on, say, the beauty and sinuousness of bodies, or silk knickers, music and wine – lines of enquiry that can easily bring things to too abrupt a head – one considers the Spanish predilection for acronyms, or the lamentable decline in whale stocks, or the curious relationship between a liquid’s viscosity and its meniscus.

There are plenty of such things but it’s sometimes hard to fish them out when you need one. However, there was a silver crucifix on top of the telly, and this put me in mind of the mines of Potosí in Bolivia. Now there are few topics better conceived to banish impure thoughts than the horrific treatment imposed by the

conquistadores

on the

indigenous populations of South America. My coursing blood was instantly stilled.

‘Can we talk?’ I suggested, thinking to lower the tension by means of some banal conversation.

‘Of course we can. What do you want to talk about?’ The

curandera

applied a little more talc.

‘You said that I don’t have to be a believer to benefit …’

‘No, no, not at all. It makes no difference. I’ve treated all sorts, all the local boys – and they’re not believers, I can tell you. The doctor sends them straight to me nowadays; he knows there’s nothing he can do.’

She went on to tell me how she first realised she had the ‘gift’. At the age of nineteen she had felt compelled to stroke the skin of a baby who was suffering from a painful skin complaint: ‘I don’t know why; I just had this urge, so I asked the mother if I could hold the poor thing. I picked it up and stroked it where it was sore, and it stopped screaming. I went back every day, and by the end of the week it was healed … I’ve been doing it ever since, about forty years now, it must be. People bring me all sorts of things to cure …’ She paused. ‘And I’ve seen an awful lot of penises. There, that ought to be done now; you can put it away.’

I buttoned up thankfully while the

curandera

returned the talcum powder to its drawer.

‘How does it feel now?’ she asked.

‘Well, I’d be lying if I said it was better, but that was very soothing, and I think it’s less painful.’ And I meant it.

‘Come again tomorrow morning, but not too early.’

‘It won’t be that early; it took me four whole hours to walk here …’

‘Walk? You didn’t walk all the way from down there!’

‘I did indeed.’

‘What on earth for? Why not drive like any sane person?’

‘Well I like walking, and … I thought it might be more appropriate for a thing of this nature, more … spiritual?’

‘I’ve never heard such nonsense. Heavens, no. Bring the car tomorrow; it’ll save you a lot of time.’

The next day I took the car. I wanted to be home for lunch, for one thing, and it meant I could take some gifts – homemade apricot jam, a sack of oranges and a bag of aubergines. The

curandera

’s village is too high for orange trees, and that year we had late aubergines.

After the third treatment, the inflammation had almost disappeared, and I asked how much I owed.

‘Come and see me one more time in a week and we’ll check that it’s all over,’ she said. ‘And, as for the money, you don’t owe me a thing. I don’t do cures for money.’

‘But … but,’ I spluttered. ‘Nobody does anything without money. Have you never taken money, then?’

‘I’ve never really thought about it, but it’s a gift, and it wouldn’t seem right to accept money for it.’

I looked around the little room. The

curandera

was far from being a wealthy woman. She had told me that she took whatever work she could get: cooking, cleaning, grape and olive harvesting and suchlike.

A week later, the day of the final checkup, I rose in the very best of spirits. A cool winter sun was pouring from a cloudless sky, and there wasn’t the slightest twinge of

unpleasantness from my trousers. On such a day the only way to go was to walk, and I rocketed up the hill like a jack rabbit. Gone now the bandy-leggedness, no more the hoots of pain from the penis. There was a skip in my step as I entered the

curandera

’s village, where I found her sitting on a bench in the sunshine, passing the time of day.

After a last brief session with the talcum powder, we agreed that my ailment was good and gone, and sat in the kitchen for a while exchanging aubergine recipes. I gave her some olive oil from the farm and a box of home-made quince jelly.

On the way back, the dogs skipped about in the scrub, visible only by their tails held high – and if I’d had a tail myself, I think I’d have wagged it right off. We were all feeling that good. And as we breasted the rise where the long descent into our valley begins, I stopped for a bit to admire the lowering rays of sunshine making shadows in the folds of the sierras. The gentlest evening breeze rose from the bowl of the valley. It was the time and place, I reckoned, for a leak.

I looked about me and sought out a plant that would benefit from a warm watering with nitrogen-rich, pathogen-free pee. A tiny, perfectly formed juniper bush presented itself and I gleefully soused the little plant, while a million billion infinitesimal wind-blown particles rose from the valley, bathing us in an invisible cloud … But what did I care? There was always the

curandera

up the river.

‘

T

IMES ARE HARD AND GETTING HARDER

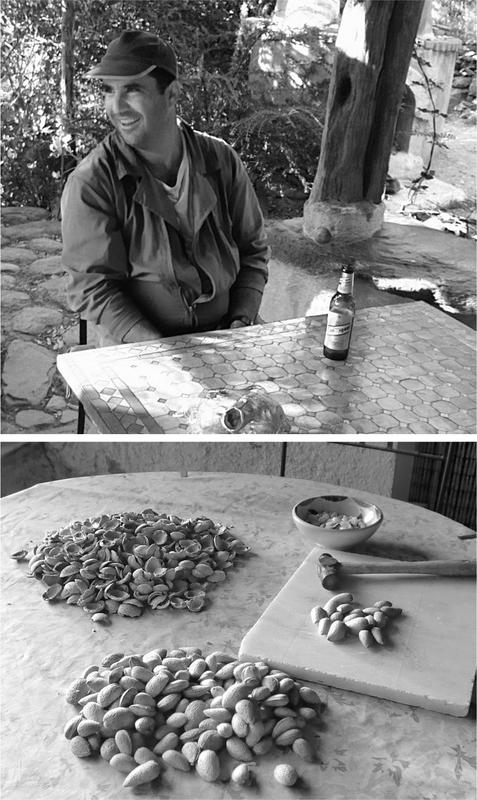

,’ said Manolo, idly crushing a beer can. ‘People are eating cats.’ It’s hard to leave a statement like that hanging. I cracked a handful of almonds and looked him in the eyes.

‘

Hombre

, how do you know that people are eating cats?’

‘Because’, Manolo explained slowly, ‘Juan at the Venta was delivered a box of rabbits last week and four of them had no heads on.’ He leaned back with an air of finality.

I considered the information aghast, though still a little bit baffled. Finally I could contain myself no longer. ‘But what have headless rabbits got to do with the eating of cats, Manolo?’ Ana was all ears too, and we both looked at Manolo quizzically as he took the floor.

‘Everybody knows …’ he intoned in the manner in which one might address a halfwit, ‘… everybody knows that a rabbit without a head on is in fact a cat … or was.’ He regarded us with a smile of triumph hovering above his thick black winter beard. But we still didn’t get it.

‘Friends,’ he continued patiently. ‘A skinned rabbit looks exactly the same as a skinned cat except for the head – and that’s because of the ears. Cats’ ears are different from rabbits’ ears,’ and he looked at us in order to be sure that we were with him on this most basic of zoological points, ‘but apart from that they’re identical.’

I cracked another dozen almonds – crisp and clean, one stroke only with the hammer – and reflected that, cat-rabbits or not, Manolo was right: times in Spain are hard, and, as he says, getting harder. I was in a junk shop last month, and the owner told me that a man had brought in a pile of what was essentially valueless rubbish; nobody would have paid a penny for the lot. When the dealer told him this, he almost wept. ‘But I need money,’ he said. ‘My family has nothing to eat.’

The catch-all (or catch-most) welfare system that exists in northern Europe has no equivalent in Spain: you pick up benefit for a certain period, depending upon how long you have worked, but it soon ends and you are thrown upon the mercy of family and friends. As I write, there are more than a million households in the country where nobody has work; there is absolutely no money coming in at all. It’s hard to imagine of twenty-first-century Spain, but people are hungry.

I kept on cracking nuts. It was what we call the

Hora de Manualidades

– Handicraft Hour – the time that Manolo comes up for a drink at the end of the day’s work. He enjoys a bit of company at the end of the day because he usually works on his own, and manual farm work gets lonely. Manolo drinks beer and we drink a Turkish sort of tea; we neither of us drink beer, and five in the afternoon seems a little early to start on the wine.

Sometimes we sit for as much as an hour, chatting in a desultory sort of a way. Manolo, it has to be said, is not the world’s greatest conversationalist, so when on the odd occasion we run out of subjects of mutual interest, we lapse into long and comfortable silences. We have found that these are more agreeable on both sides if we are engaged in some sort of activity, something that is compatible with the desultory drone of intermittent conversation … and, of course, it gets things done.

The most obvious

manualidad

is almond-cracking. I bring to the table a bucket of Marconas, my favourite almond, sweet, fat and easy to crack. I spread an old towel and a cracked piece of marble on the table, and take a hammer I keep specially for the purpose. I spill a heap of almonds on the table and we set to cracking them. In an hour Ana and I between us can do a kilo – and that’s a lot of almonds. Afterwards I blanch them, slip the inner skin off, toast them and mix them with a little olive oil, ground salt and

pimentón

. I defy you to come up with a simpler or more delicious thing, and all it costs is our labour, because we happen to have our own Marcona trees.

It has to be said, though, that the constant crack of the hammer doesn’t aid conversation. So sometimes Ana will do some sewing; I might find something broken to fix. At various times there is garlic to string, or onions or home-grown tobacco. Or there is the satisfying task of shucking

habas

, broad beans. We eat the tender young beans and put the pods in a bucket for the sheep, who love them, and at the end of the season get to eat the plants, too.

These are timeless farm activities. If you talk to the old folks of the Alpujarra about the way things were before modern times, they all remember gathering at

cortijos

to share the task of shucking or ‘podding’

habas

, shucking maize, stringing garlic and peeling onions. After the

habas

were shucked, or the onions peeled, inevitably somebody would bring out a guitar or a mandolin and everybody would end up dancing on the roof in the moonlight … which upon not a few occasions would lead conveniently to that other pleasurable cooperative activity of getting together to fix a broken roof.

I don’t wish to appear too cynical about this, as the idea of dancing by moonlight on a flat roof in the remoter fastnesses of the Alpujarras to the sound of a mandolin, after a long hard day of

habas

-shucking, is about as romantic a thing as I can think of. And life in rural Spain, as we know, was unbelievably hard back then; there were few luxuries, and the idea of being delicate about eating would not have been well considered. Which perhaps explains the pained expression that Manolo adopted when we took to the somewhat refined

manualidad

of ‘double-podding’

habas

.

Now, this is an activity that seems almost wilfully wasteful of time – ‘

una

mariconada

’ (an unmanly frippery), as Manolo pronounced it the first time I set to the task. However, I’m not so sure. As everybody knows, unless you pick it very early in its life cycle, the broad bean has a detestable flavour, like overcooked liver; it dries the mouth and leaves the palate with a disgusting after taste. The reason for this is the bean’s coarse, grey-green outer skin. If, however, you blanch your

habas

for a couple of minutes, and then proceed to slip them out of their skins, you get the most exquisitely delectable food – bright green, tender and

deliciously flavoured. It’s a lot of work, and a bit boring … but it takes only seventeen minutes to prepare enough for four servings.

It’s much like the business of squeezing

altramuces

out of their skins and into your mouth, and people pay good money for that.

Altramuces

are curious yellow beans with no flavour that are unaccountably popular as a

tapa

in Sevilla. The technique is to squeeze them with your fingers and let the inner part of the bean shoot into your mouth, leaving the outer skin between your fingers. It’s a dish, and an activity, that wears thin very quickly … unless you happen to be from Sevilla.

The whole broad bean business had particular relevance that year, as Manolo, for some reason known only to himself, had sown about half an acre of

habas

, and we had had the most successful crop I had ever seen.

Habas

do well here, and it’s the staple diet during the earlier part of the year. But even in this bumper year, when we could have picked every bean in its tiny delectable state, we found ourselves double-podding, for Ana insisted we pick the horrible old coarse ones first – so as not to waste them. What this means, of course, is that by the time you have got through the big horrible ones, the thin tender sweet ones have all in their turn become fat and horrible. It’s the same with the raspberries, later on. Ana insists we eat the over-ripe fruit before we’re allowed to get at the nice juicy fresh ones. By the time we get round to picking them they are rotten, too, so we only get to eat rotten raspberries … just like the ’orrible ’abbers. It’s a deeply flawed system.

But to return to the task in hand. Before the second shucking of the

habas

, you have to get the beans out of their big pod. Ths is not unpleasant work and you can get through it tolerably quickly. But Ana considers it one of those jobs that must be combined with other activity, and, outside of our hour with Manolo, the best activity to combine it with is listening to audiobooks. Again I’m a little ambivalent about this as I have a sneaking, fastidious sort of a suspicion that I am detracting from the meaningfulness of both activities by combining them. However, that spring we had sackloads of

habas

to shuck, and so we both settled down with a bowl between our knees and headphones on our heads. You may perhaps wonder why we could not listen to the book together, as would seem to be logical. This was because, although we were listening to the same book (

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

by Carson McCullers … and I defy you to come up with a finer novel), we were at different stages of it, on account of my having snaffled a couple of tapes to take on a car journey to Granada. I was therefore way ahead of Ana and as I didn’t want to hear the earlier bits all over again, and she didn’t want to skip any of the intevening parts, we had to resort to separate audio equipment.

So imagine us, if you will, of an evening, me sitting on the pouff, the Wife on the sofa, both engrossed in the story being read separately to us. Between us the bucket of unshucked

habas

was diminishing slowly, while the piles of podded beans in the bowls between our respective knees grew at an equal rate. Our faces were rapt in earnest concentration, except for every now and then when one or other of us would have a comment to make, more often than not upon the size or shape of some spectacular pod.

Ana would kick me and, as I looked up, signal to me to turn off my little tape player. I would fumble at the controls and eventually achieve this simple task. Then I would take the headphones off and look at her expectantly. She had already gone through similar motions. Then she would hold up a bean. ‘Look at this one,’ she would say. ’How about that for a big bean?’ I would chuckle obligingly and, having ascertained that she didn’t want to comment any further upon the morphology of the bean in question, would return to my tape … until several minutes later I too might find myself sufficiently moved by the shape of a bean to want to put the whole process in motion again.

Of course, this procedure detracts to a certain extent from the sense of continuity of the book … it’s as I said, I’m not sure it’s the right thing to do. And when I think of those Alpujarreños of old sitting round together shucking

habas

and talking by the light of the fire, waiting for the moon and the mandolin … well, I know what they mean, those old folks, when they say they reckon that we have lost something.