Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

Last Days of the Bus Club (27 page)

‘I had a friend’, I continued, ‘who would go to concerts and listen to the orchestra tuning up. He loved that anarchic, random sound, as all the strings and tubes and skins that constituted the instruments of the orchestra slid up or down from wherever they had been to meet finally in one great glorious harmony. Then, as soon as the musicians had finished tuning, he would get up and leave. “Nothing”, he said, “that the orchestra could do afterwards, could possibly compare with the sweet anticipation of the tuning up.”’

Even I could see that I was heading for the rapids here. I cast down again at my scrap of paper for rescue. ‘Thank the dignitaries,’ it said.

Now, I am told by my daughter, who is a person suspended between the worlds of Englishness and Spanishness, but more critical of the English, that we English have the vice of saying ‘thank you’ much too often. But it has to be said that, when it comes to formal speeches, the Spanish are in a different league: they name everyone by name and thank them till they’re blue. I looked behind me at the gently rocking row of dozing dignitaries. I’m not good at names, particularly in Spain, where a certain paucity in the name department means that almost everybody has names that are confusingly similar. Mari-Ángeles I knew … but was it Mari-Ángeles Vílchez Martín or Martín Vílchez? As for the other dozen or so dignitaries, I knew that there were liberally spread amongst them Garcías, Vílchezs, Ruizs, Morales, Romeros, de la Torres, Almodóvars and de Almodóvar Sels … preceded by a seemingly random selection of Antonios, Isabels, Marías del Mar, Josés, Pepes, Pacos, Vanessas and Manolos. But I couldn’t for the life of me remember in which order they went, nor to whom they referred.

I hedged. I would do something new, taking advantage of the prerogative of being a

guiri

. After all, what are

guiris

for but to effect changes in the stagnant status quo? Turning towards the municipal worthies, with a sweep of my arm I offered a great all-encompassing blanket of thanks.

‘If you feel you deserve a little bit of this great body of gratitude, please feel free to take it,’ I announced to the company assembled behind me. ‘It’s big and it’s cheap, and there’s plenty of it.’

And so finally I turned to my theme of

convivencia

. This has become something of a buzzword in Spain and is used by social commentators to look back on that state of harmony and tolerance that supposedly extended to the three communities – Muslims, Jews and Christians – back in the days of the Caliphate of Córdoba.

Convivencia

, of course, came to an end pretty sharpish after the conquest of Spain by the Christians. But one lives in hope – and perhaps Órgiva is a beacon. For some unaccountable reason, we have just about the richest mixes of nationalities in the peninsula. There are Algerians, Argentines, Americans, Chinese, French, Germans, Romanians, Czechs, Moroccans, Sahrawis, Poles, Dutch, Lebanese, Uzbeks, Iranians, English, Swedes, Danes, Bulgarians and Turks … to say nothing of the more local

Zamoranos, Leoneses, Madrileños, Jiennenses, Gaditanos

and

Onubenses.

I told my audience that when I arrived here, twenty-odd years ago, the mix was not quite so rich. There were a few Danes and Dutch, and some English scattered thinly here and there. The

Alpujarreños

were generally quite interested to observe these foreigners with their strange habits, although there were one or two who did not see it as a good idea. My neighbour Domingo once went to town to buy some

habas

to sow. Our Dutch neighbour, Bernardo, asked him to buy a bag for him, too. Arriving at the seed merchants, Domingo said: ‘Give me a kilo of

habas

and another for Bernardo.’ The manager looked at him and said: ‘I don’t sell to foreigners.’ ‘OK,’ said Domingo. ‘Make that two kilos for me, then.’ Such simple little acts are the roots of

convivencia

.

‘Things have changed,’ I continued, warming to my theme, ‘and I believe they might have changed just that

little bit faster and in a more imaginative direction as a result of the richness and variety of the mix of ethnicities and nationalities. I wouldn’t say that all change comes about as a result of

forasteros

, for perhaps the very best of those who seek to change and improve the life of the Alpujarras come from local families, but I do believe that the mix of races and nationalities provides a strong impulse for change and improvement.

‘There are still, of course, those who refuse to accept the benefits and mutter in the gloomier corners of bars about the foreigners who come and muck things up for the others … but there always have been types like this. No doubt,’ I suggested, ‘there were some grumpy old Ibero-Celts who would have said the same of the Phoenicians. The less progressive Phoenicians would have moaned about the arrival of the Greeks; the Greeks certainly would have complained about the Romans, and the Romans been equally sniffy when the Visigoths moved in. When things started to go wrong for the Visigoths, and the Berbers turned up to sort things out, there were those who saw it as a bad thing. For seven hundred years things went more or less alright, until the

Reyes Católicos

, the Catholic kings, came along and the denizens of Granada would mutter to themselves how things had been going along perfectly well until these latest foreigners arrived and mucked things up again.

‘And each of these successive invasions,’ I insisted, ‘brought with them their own innovations to enrich and enliven the land they had settled. The orange tree, for instance, and the olive, the aubergine and the almond, tobacco; Christianity, Islam and Christianity again; the dome, the horseshoe arch, the patio garden, the lovely Alpujarran village.

‘And I’m proud to be a part of this village,’ I continued. ‘A village that understands more than most about

convivencia

, because, although there are difficulties and things are not always easy, you, admired

Hueveros

, have more than a full measure of tolerance and patience. And you know, in the best traditions of this blessed country, how to enjoy and benefit from the influence of new arrivals.’

I glanced once more at Ana, who was holding up a glass of whisky and grinning at me. A sure sign that I needed to bring my

pregón

to a close.

‘So, at the risk of talking and behaving even more like a

guiri

, thank you,

Hueveros

, for making us welcome in this patch of paradise for the last twenty years; thank you,

Hueveros

, for looking after and playing with my daughter in the alleys and patios of the village, and making of her childhood, and our lives, a time of joy and pleasure. And thank you, too,

estimados Hueveros

, for the inspiration you have given me over the years.

‘¡Basta ya de pregón!

Enough of the

pregón. Hay placeres que nos esperan.

There are pleasures awaiting us.

¡Al timón!

To the tiller!’

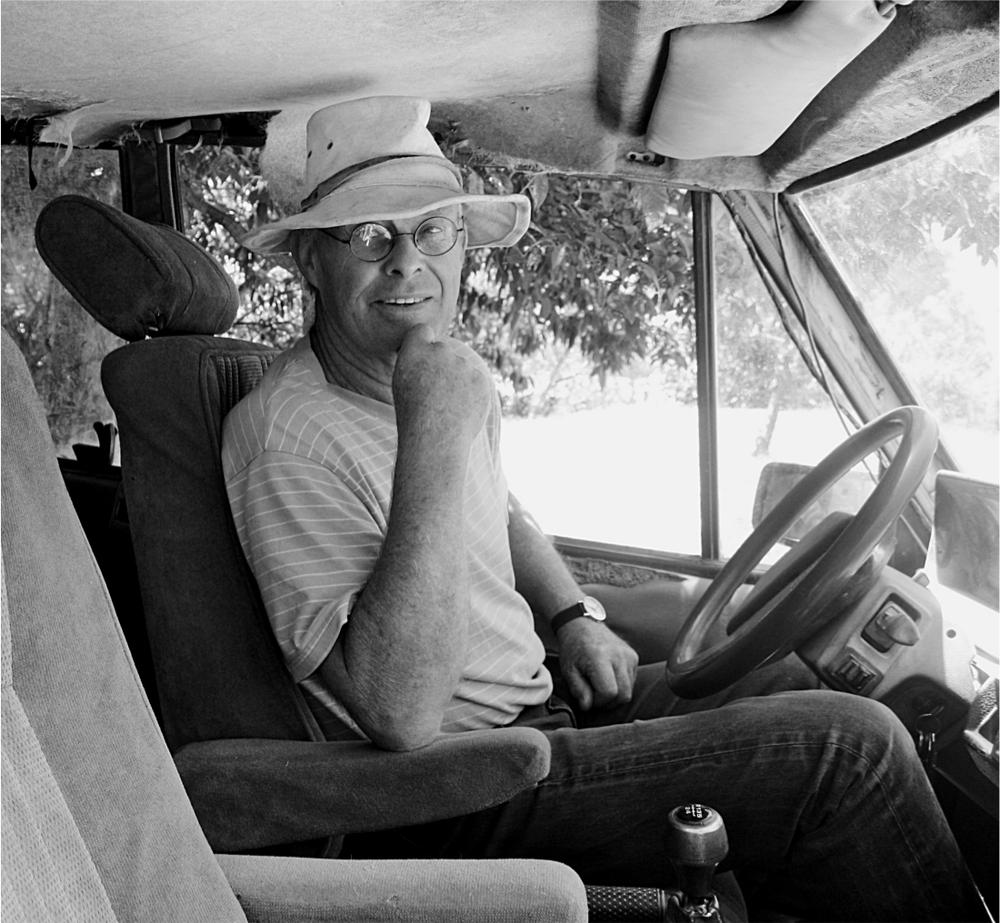

Chris Stewart

’s first book about Spain,

Driving Over Lemons

, told the story of how he bought a peasant farm in Andalucía, located on the wrong side of the river and with its previous owner still in residence. The book became an international bestseller, along with its sequels,

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree

and

The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society.

His last book,

Three Ways to Capsize a Boat

, recalled his misadventures as a novice yacht skipper in the Greek islands, and sailing to America.

Chris was the original drummer in Genesis (he played on the first album). He then joined a circus, learnt how to shear sheep and went to China to write the

Rough Guide

, before moving in 1988 to the Alpujarras, south of Granada, where his daughter Chloé was born. He still lives at El Valero, his beloved mountain farm, with his wife Ana, and their sheep, dogs, cats and chickens.

THE DRIVING OVER LEMONS TRILOGY

Driving Over Lemons: An Optimist in Andalucía

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree

The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society

A SAILING MEMOIR

Three Ways to Capsize a Boat

Last Days of the Bus Club

© Chris Stewart 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

All photos © Sort Of Books on behalf of the photographers: Maggie Harris, Arezoo Farazad, Ana Exton, Carole Stewart, Stefan Tolde, Martin Orbach, Pedro L. Barberá Briones, Andrew Phillips and Mark Ellingham. Thanks to them all, and thanks especially to Maggie for the photo shoots, to Nikky Twyman for proofreading, Henry Iles for text design, Peter Dyer for cover design, and Chris Andrews for the cover illustration.

Published in June 2014 by

Sort Of Books, PO Box 18678, London NW3 2FL

www.sortof.co.uk

Distributed by the Profile/Independent Alliance and TBS in all territories excluding the United States and Canada.

Typeset in Iowan Old Style BT and Vitrina to a design by Henry Iles.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

288pp

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

e-ISBN: 978 1 908745 44 6