Last Days of the Bus Club (21 page)

Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

‘¿Qué te pasa?’

asked Guerrero, seeing my consternation.

‘It’s the English. You can’t let it go like this, Rafael.’

Rafael seemed crestfallen.

‘Don’t worry,’ beamed Guerrero, ‘Crease can sort it all out for you. He’s a writer, that’s what he does,’ and he nodded at me conspiratorially. This would be a tough act for the

Búlgaro

to follow.

‘Well, OK. I should be able to do something about it …’ I agreed, a little hesitantly.

‘Good,’ said Guerrero. ‘My friend here will put it into perfect English for you while we discuss a bit of business.’ Like many of my Alpujarran friends, he had no concept of translating or writing being work at all. An hour and a half later, feeling a little befuddled by all the linguistic tangles I’d been unravelling, I joined José and Rafael for some coffee at the bar. ‘Come and see the farm,’ suggested Rafael.

So we stepped outside, where dark was falling into an icy cold night. The sheep shed was enormous, like an aircraft hangar, but graceful, with soaring arches of laminated wood, a deep bed of clean golden straw, and in the hay-racks the sweetest-smelling hay. There would be worse places, I thought, to be a sheep. As we wandered through these perfumed halls the great door at the end opened and in trooped the flock, eight hundred strong. They ambled in contentedly, their bellies full from the day’s grazing out in the fields. José and I sighed as one with deep admiration for such a fine flock of well-kept and beautiful sheep. For all of our differences, this really did it for the both of us. The fractiousness of the day disappeared as we grinned inanely at each other, united in honest admiration of the ewes. Churras they were, with black and white faces, much like a Kerry Hill, but with fine long, almost bouclé, fleeces. We sighed together again.

‘They’ll be lambing in January,’ said Rafael. ‘And we wean and slaughter the lambs at around twenty days.’

Twenty days?! That’s not even three weeks. I was astounded. We sell our lambs at nine months to a year.

‘It’s what the market wants,’ explained Rafael. ‘It’s

lechazo

– suckling lamb. If the lamb has ingested anything other than its mother’s milk, then it’s disqualified; it won’t have that delicate flavour and tender texture people want.’

‘Well, I suppose that’s true, Rafael, but it seems to me such a terrible waste, and even a little barbaric, to slaughter lambs at three weeks old.’

‘Depends how you look at it, Crease. They’re going to be killed anyway; probably doesn’t make that much difference to them when.’

This is a big debate and I wasn’t about to go that deep into it right then, so I let it go.

Guerrero nudged me. ‘Give him a book,’ he said. ‘You know, the one with me in it …’

Rafael thanked me for the book and looked warily at it.

‘I’m afraid I don’t have much time for reading – I’m just too busy. I never seem to stop. I’m just going to grab a

bocadillo

now and then I’m off ploughing. I’ll probably be out half the night. Thanks very much, though; it’s very good of you, but I’m afraid’, he admitted with an apologetic sigh, ‘I can’t see myself reading it.’

It was dark when we crossed the river bridge into Aranda de Duero. We parked the car and walked into the old town, which, even at nine o’clock on a cold November night, was thronged with people. José was looking for a particular

bar, where, presumably, we were going to meet Jesús and Eugenia. The cold night air and the prospect of a good meal perked me up and, if I was to be honest, I had begun to look forward to the company of people who were readers. I couldn’t help but have a sneaking interest in what they had enjoyed so much about my books and felt it would make a welcome change to shift the discussion from the omnipresent sheep. We traipsed back and forth searching for the right place.

‘Ah, this is it,’ said José, and we burst from the dark into the bright warmth of a big noisy bar. The Asador de Aranda was a temple to good eating and drinking, with serried ranks of glittering wineglasses, great dark barrels of wine, dishes of indescribable beauty being hurried to and fro, and a hubbub of conviviality and bonhomie; there pervaded a sense of eager and guiltless anticipation of pleasure. This is how it is in the north: they take their food and wine seriously; the waiters and bartenders wear white shirts, waistcoats and bow ties, and are respected professionals.

The torpor that the long hours on the motorway had induced simply sloughed away as I was drawn in by the brightness. ‘Ah, there they are,’ announced Guerrero, pointing to a couple standing wreathed in expectant smiles by the bar, who I rightly took to be Jesús and Eugenia. They were with a group of friends, and we all kissed and shook hands and bobbed about a bit in the customary quadrille that attends such occasions. A glittering schooner of darkest red wine appeared as if by magic in my hand and the conversation rolled away.

‘So, Crease,’ began Eugenia. ‘Where do you live?’ It seemed an odd question. My books are, after all, memoirs about my life in the Alpujarras.

‘The Alpujarras, near Granada, like in the books,’ I replied, trying not to make it sound too pointed. She accepted the information without comment and, before we could continue, the first

tapa

arrived. It was a potato, a small exquisite potato with a salty crust, and it was followed by more wines and more

tapas

, each more exquisite than the last. Guerrero began holding forth on our day’s drive and his latest campaign to put one over on the

Búlgaro

, so it was a little while before I could resume my conversation with my greatest fans.

‘Looks like a beautiful town,’ I said. ‘And the food and wine are terrific. I wish Ana had been able to come and enjoy it, too.’

Eugenia, who oddly enough is not a wine drinker, took a sip of her beer; Jesús finished his wine. They both nodded.

There was a pause, then Jesús asked, ‘Who’s Ana?’

Eugenia was all eagerness to know, too.

It was my first inkling that Guerrero had been a bit liberal with the truth.

Neither of them, it transpired, had actually got round to reading the book that José had given them. But in the event it mattered not a jot. There was something right about Jesús and Eugenia that I recognised the minute I saw them: an immediate welcoming warmth, which I basked in and returned. And they made wonderful wines. Maybe there is some subtle alchemy that flows through the winemaker, their vines and wine. I like to think so and, if there is, then it is one more persuasive argument to drink wines from small-scale producers rather than the big operators, in which all trace of alchemy is obfuscated by the industrial chemical process.

So why the gift of wine, then? To cut a long story short, they had read about me in an article in

El Pais

. Guerrero had

filled them in and told them that we were friends, and they were thinking of selling their wines down in Andalucía. They were also, quite simply, extremely generous.

The next day, having stacked the car with crates of wine till it groaned and sank down on its haunches, we began our journey west. I wanted to stay behind and hang out with my new friends Jesús and Eugenia, but Guerrero wouldn’t hear of it; he needed me and my famousness to clinch his deals, keep one step ahead of that

cabrón búlgaro

. That was OK: I had loosened up. And besides, there was still a lot of Spain I wanted to see … even at 160 kilometres an hour with all the goddamn windows open.

In the next few days we criss-crossed the country, visiting dozens of places, meeting dozens of shepherds and a whole lot of fat fish, leaving them all looking just a little bit baffled and holding a book they would never read.

Our final port of call was Cáceres, way out in Extremadura near the Portuguese border. Cáceres, and nearby Trujillo, are the towns that the

conquistadores

, Cortés, Pizarro and the boys, came from, and enriched with what they pillaged and plundered from the innocent lands and peoples of the Americas. As a consequence they are furnished with a wealth and architectural distinction unusual in towns so small and remote. I had always harboured a desire to visit them, but never made it until now.

There are a lot of sheep, too, in Extremadura, and there was plenty to keep Guerrero occupied in the town. On that day I was not expected to dance attendance in my role of Mister Famous – this was not unconnected to the

fact that the fat fish of the Cáceres sheep society was the most dazzlingly gorgeous, auburn-maned woman. Guerrero wanted the field to himself. Accordingly I was despatched to do some sightseeing in the company of Pablo, a sheep farmer who had fallen on hard times and lost his farm.

Poor Pablo was just one more of thousands of victims of the greed and venality of the country’s bankers and financiers. He didn’t make an issue of it, though, didn’t let it get him down, and he was the most delightful guide as we strolled in warm winter sunshine around the beautiful town.

I asked Pablo how he filled his time, now that his farming enterprise had gone down the tubes.

‘I keep myself busy with a little of this and a little of that,’ he told me. ‘I grow a few vegetables, take long walks when I can, and, well, I do a bit of reading,’ he added shyly. We were in a bar by now, sipping coffee and grinning in collusion as we observed from across the road the antics of the dastardly Guerrero dancing craven attendance on the beautiful sheep woman. Pablo opened his bag and drew out a well-thumbed and scuffed copy of my first book. ‘I was wondering if you could sign this for me,’ he added, gazing down at it earnestly.

It had been a beautiful morning.

I

T’S ALWAYS THE SAME

when the Critchley Road Primary School kids come to visit us on their annual trip to Andalucía: the bus driver takes one look at the road and flatly refuses to go any further. The teachers wheedle and implore him for a bit and then they ring me up, and I wheedle and implore for a bit on the phone, but knowing full well that our man is a bit of a jobsworth and is less than keen on the idea of graunching the paintwork on his shiny new bus, nor indeed tipping a score of schoolkids over the side of a cliff. ‘They’ll have to walk,’ he says.

It was a nice day for a walk, but these were city kids and walking wasn’t their thing. The remaining journey was about four kilometres, starting with a long steep ascent. They stood on the road and looked up, as if scanning the north face of the Eiger.

‘We can’t go up there, Miss. It’d kill us,’ was the general consensus.

The obvious solution was for me to go and fetch them in the Land Rover, a couple of journeys. It was not much to ask, but I let them stew a bit before setting off, so they could at least make a start on the hill, get a little fresh air, take in the view, before I arrived with the car. On the way I came across none other than Juan Barquero, who was about to load his trailer with firewood. I looked at the trailer and it occurred to me that I could fit the whole lot in on one trip. From a ‘health and safety’ point of view, this scheme was perhaps a little ropey. But so much, the better.

Juan didn’t need his trailer till later in the day, so we connected it up to the Land Rover and off I went, the trailer bouncing to and fro on the rough track and clattering and clanging like the hammers of Hades. A few of the more competitive spirits had actually made it to the top of the hill by Cuatro Vientos, while the rest trailed doggedly a long way behind. As I clanked round the corner into view, a dozen kids fell upon me, panting and wailing.

As I had suspected, they all wanted to go in the trailer. ‘I never bin in a trailer before, Mister,’ said one lad, as if this was a form of local transport hitherto denied him. Another boy said he would prefer to go in the car with the teachers. ‘Very sensible, too,’ I commended him, although I thought it was a little unadventurous. Apart from this boy and two of the teachers, Amina and Rukhsana, everybody clambered into the trailer and I shut the tailgate. The level of excitement was palpable, with everybody shrieking and yelling fit to bust and pretending to be terrified. And all this before I’d even started up the engine.

I set off, not so slowly as to be a spoilsport, just enough to give them a bit of a swing and a bounce, but neither so fast as to be unsafe. Of course, it was safe as can be, and Jim

the headteacher was with the kids in the trailer, just in case. Jim told me that he suffered from vertigo, which made his decision to ride shotgun with the kids all the more noble. Now, I have driven this track a thousand times, but it’s only when you have a trailer on behind, loaded with raucously screaming kids and a man with vertigo, that you become aware of just how desperate it looks. The track is the most precariously thin ribbon, cut high into an almost vertical hillside, with sheer drops to dizzying depths down in the river below. It’s not quite Peru or Bolivia, but it’s not far off it. To get them all riled up I put my foot down a little on the straight bits and gave them a bit of a swing around the corners. They loved it and howled and screamed like a bunch of banshees if we came even within metres of the edge. It was a long time since I had heard such a pandemonium of euphoria and excitement. The sun shone; the way was lined with spring flowers; the river was roaring below; the day was getting off to a flying start. Most of these kids had never been out of the city, and the country was putting on a big show for them today.

Meanwhile Ana was at home busily putting the finishing touches to the lunch. The Critchley Road contingent tends to be heavily weighted with Muslims, which is why in the last couple of years, to avoid a fuss, we have supplied them with Halal chickenburgers for lunch. These went down pretty well, inasmuch as any food is met with enthusiasm by eleven-year-olds. We couldn’t face the burgers ourselves, though, knowing, as we do, a little bit about the sort of conditions that those poor cut-price chickens are kept in, the unspeakable stuff they’re fed on, and the gruesome manner of their demise. ‘You can taste the misery in the meat’, in the immortal words of Garrison Keillor’s aunt.

This year Ana and I had had a ‘discussion’ about the burgers. I sort of liked cooking them on the barbecue, and I reckoned that the elemental aspect of the fire and the smoke associated with the food they were eating would be exciting for the children.

‘But why should we give them those disgusting things when it goes against everything we stand for?’ asked Ana.

‘Because it’s what kids like,’ I suggested.

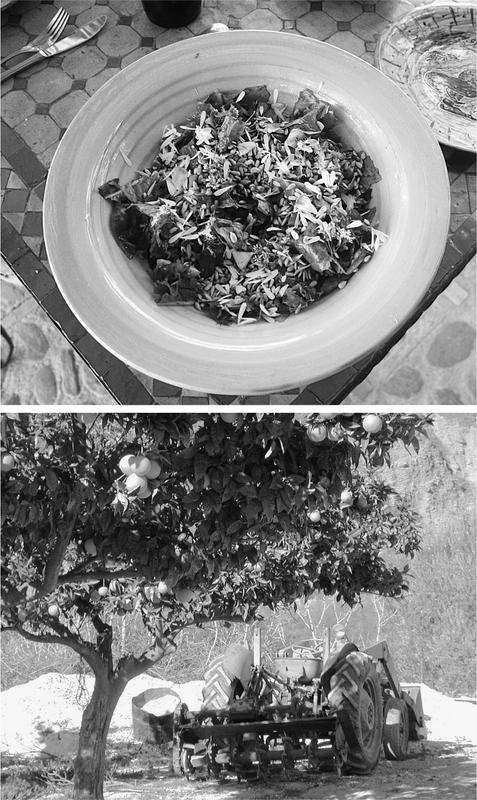

‘Be that as it may, this year we’re going to do things differently. I’m going to make them a beautiful floral salad and

tortillas

made with our own glorious eggs.’

‘But they’ll never eat salad,’ I cried, aghast.

‘Well, that’s what there’s going to be; they’ll like it once they try it and it’ll be a whole new experience for them.’

And so that was that; Ana’s decision was final. She also made home-made lemonade with lemons freshly picked from the tree, and biscuits with a face on and chocolate for hair.

Ana had given me instructions to delay the arrival of the kids as long as I could, because the chocolate hair on the biscuit faces was taking longer to dry than she had anticipated, and this had for some reason thrown all the gastronomic arrangements into disarray. The fortuitous business with the trailer, although it had taken the fun factor through the ceiling, was having the opposite of a delaying effect.

I decided to play for time. Halfway along the track, above La Herradura, is a ruined

calera

, a lime kiln. All that remains is a crumbling stone wall half buried among the wild scrub, with the form of a circular beehive. I pulled up beside

it and got out. The kids looked at me in open-mouthed amazement.

‘This is a culture stop,’ I announced. ‘Anybody know what this is?’ I indicated the ruin.

‘It’s your ’ouse,’ called some wag.

‘No, it’s a lime-burning kiln. Anybody know what it was for?’

Hardly surprisingly, nobody did.

‘Well it was how they made cement in times gone by. They would gather firewood from all around and make a big fire to burn limestone rocks. After a few days of burning, the rocks would crumble and they could be used like cement for building houses and suchlike. These kilns are all over the Spanish countryside and it was probably the lime-burning, as much as the construction of the Spanish Armada, that contributed to the lack of trees. You’ll probably have noticed that there are not an awful lot of trees here.’

Nobody had. Why would they? They were from the city; they had probably never given so much as a thought to how many trees there ought to be in the countryside.

To complete the educational element of the tour, I told them the story about the wild boar and how the activities of the

leñeros

had caused their numbers to dwindle until the introduction of butane gas put matters right again.

‘Sir, are there boars ’ere, then?’ asked one of the girls.

‘You’re a bore,’ interjected the wag, inevitably.

‘Yes, lots of them. They’re all over the place,’ I rabbited on, ignoring the wag. But now everybody was looking around and pretending to see wild boars. These kids had a shorter concentration span than I did. Still, I had won a good ten minutes for Ana and her wet chocolate hair.

I climbed back into the car with the sensible boy and the two teachers, and we set off once more, making a hullabaloo that you could probably hear as far as the coast.

The next delaying tactic was Antonia’s

pollino

, the baby donkey. I parked the car and trailer by the bridge and we set off through the fields beside the river. The grass was deep and lush and shot with buttercups and daisies and poppies. Big yellow butterflies fluttered to and fro amongst the almond trees. By the river was a line of orange and lemon trees, the ground covered with fallen fruit. The kids didn’t know where to look first: the river was looking magnificent as it raced and roared down over the rocks. Nobody had ever been so close to a mountain river, and nobody had ever seen an orange or a lemon dangling from a tree before. And then there was the baby donkey.

‘Ooh, look! It’s sweet … Can I stroke it, can I stroke it?’

Stroking Antonia’s baby donkey was not really to be recommended, as it kicks and bites. Donkeys tend to be like that. The

pollino

and its mother strolled over to the gate to see about getting some good kicking and biting in. I suggested that we limit ourselves to taking photographs of them, then I managed to divert the kids by saying that they could throw the fallen lemons into the river.

‘There’s an old gypsy saying,’ I told them, ‘that if you throw enough lemons into the river, it will turn to gold.’ They set to this new task with a will. Throwing lemons into a fast-flowing river is about as good as it gets when you come from Ilford or wherever it is they come from.

‘Can I eat a orange, sir?’

‘You don’t have to call me sir. I’m not a teacher; my name’s Chris. And it’s

an

orange.’

‘Can we eat a orange, Chris? Can we eat a orange?’

‘Course you can,’ I said, offering this grand largesse with Juan Barquero’s oranges. He wouldn’t miss a couple of dozen. They were Washingtonia Navels, like our own, the sweetest and juiciest of all the oranges on the planet. Everyone picked an orange. I cut the tops off them and they set to peeling and eating them. Young Darren looked up at me in absolute gobsmacked amazement.

‘I’ve never ever ’ad a orange before in my life,’ he said. This puzzled me, but on reflection I supposed that he simply couldn’t equate a fruit that grew off a tree with the variety he’d seen in supermarkets.

‘Can we swim in the river, Chris?’

‘Not here, you can’t; it’s too fast and the banks are too steep.’

It was mid-March and most of the water was from snow-melt, so it was hellish cold, but I figured that fooling around in the river would occupy another half an hour and – what was more to the point – it would make them happy. So, with some trepidation, we crossed the bridge, and headed downriver towards the ford. Here, apart from the sensible boy and one or two others, everybody took off their shoes and socks, rolled up their trouser legs and leapt into the water, screaming and yelling with delight. I demonstrated how to play ‘Ducks and Drakes’, skimming flat stones across the surface of the water by spinning them with a deft flick of the finger, in order to get as many bounces as possible. Nobody was half as good as me, which pleased me no end, because normally I am the worst at the game.

Eventually we tore ourselves away from the river and walked up through the farm. By now everybody had become obsessed with the notion of picking oranges and lemons

and eating them or sucking the juice from the lemons. Each kid was clutching an armful of colourful fruit. Meanwhile I, with my trusty Opinel knife, was in constant demand for cutting them in half.

‘’Ere look, ’e’s got a knife. ’E’s well hard,’ I heard one of the kids whisper behind me, seriously impressed.

‘It’s because he’s a farmer; farmers always carry knives,’ explained Jim the headteacher, detracting rather from my new-found notoriety.

‘Is that your tractor, Chris?’ several of the kids asked as we passed beneath the tree that is the tractor’s resting place.

‘Yes, it is,’ I said diffidently. In a certain sense I suppose the world may be divided into those who possess tractors and those who don’t. The vast majority, of course, fall into the latter category.

‘Really, your very own? Is it a real one? Can we ’ave a go on it? Please Chris, please …’

‘Not now. It’s time for lunch.’ I figured the chocolate hair would be dry by now. The year before, the tractor, a rather appealing red 1960s model Massey Ferguson 135, had been the star of the show, eclipsing even the river and the oranges. The kids had fooled around with it all afternoon.