Read Last Days of the Bus Club Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

Last Days of the Bus Club (4 page)

By this time, what with all the dithering about that is the inevitable concomitant of filming, we were all starting to feel just a little bit hungry. All the talk of food and the kitchen badinage did nothing to allay this. Ana and Rick sat down at the table and I burst through the fly curtain with a pan full of hot balls. There were just the three of us eating and it was hardly the most relaxed meal I have had in my life, as there was a big fluffy sock of a microphone dangling over the table and the long snout of a camera sticking into my left ear. The hunger getting a grip now, I sat up in my chair and raised a glass of wine to my wife and the guests, and then, fairly quivering with anticipation, I speared a hot ball with my fork and raised it to my lips.

‘CUT!’ cried David.

F

EW PEOPLE GET TO SEE

their homes from above. We have that pleasure from not just one but two vantage points: one on the mountain path that leads up to what used to be a threshing floor, the other from the opposite side of the valley where a lone almond tree marks a bend in the track. The latter is the spot that I ask visitors to look out for, because if you honk your horn as you pass this tree the acoustics carry the sound all the way across the valley to the ears of the dogs. The dogs start barking, which wakes me from whatever reverie I am indulging, and leaves me just enough time to hare down the hill and meet the approaching vehicle at our bridge (as I had with David before that first fish lunch).

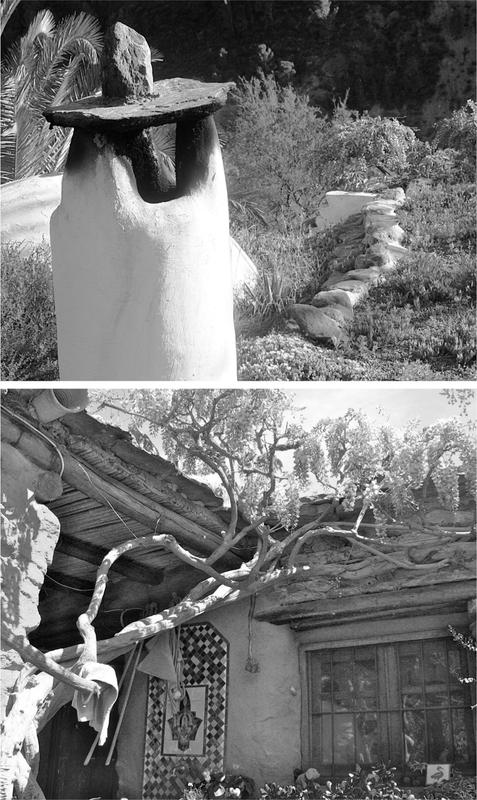

From either of these points you can make out the peculiar agglomeration that we call home: a muddle of more or less rectangular stone boxes emerging from a rocky hillside, half hidden by a riot of jacaranda, morning glory, wisteria and

jasmine. Below, you can make out a path winding down through terraces of oranges and lemons to the sheep stable and a hillock known as La Haza de la Cruz – ‘the meadow of the cross’ – which presides over the confluence of two rivers, the Cádiar and the Trevélez.

There’s something deeply gratifying about looking down on a house that you yourself have built, but what makes it even better is the innovation we’ve recently added to our otherwise traditional home and outhouses – the ‘green rooves’ of El Valero. These give the pleasing impression of tiny terraces of grass, hovering beside the outhouses, and after the spring rains have done their best the foliage on the roof becomes so thick that parts of the house seem to disappear entirely.

I sometimes wonder about our house and the building of it and our offbeat ideas. After all, what initially attracted me to the Alpujarra was the simplicity and honesty of the architecture, the attempts by the rural poor to create a little beauty with whatever lay to hand. The perfect proportions of a handsome hen house; an oil-drum set on a plinth of stone, painted white and planted with yellow and white flowers; a stone wall moulded to fit the leaning trunk of an olive tree: these were the delights that won my heart. From the point of view of authenticity I fear we may be running the risk of killing the thing we love.

On the other hand, one has to move forward, take advantage of new developments. Had we not done so we might still be living in architecturally honest turf huts, smoked half to death by peat fires. And the changes we

were making, while they gladdened our hearts with their beauty, were fairly unostentatious and, of course,

sustainable

. Our home is powered entirely by solar panels, which, arrayed upon the rooves, glint royal blue in the sunshine; we keep warm in winter by burning wood that we grow on the farm or gather from the river; kitchen and bathroom water is used for irrigation, and all the leftovers are either composted or made into edible eggs by the hens. All in all, it makes us feel pretty good about our impact on the earth in general and on the Alpujarra in particular.

The desire to add beauty to building is not universal in the Alpujarra, where function and cost is king. Witness my neighbour, Domingo, a sheep farmer and nurseryman. For the last fifteen years he has been living with Antonia, a Dutch sculptor who moved to the valley in search of inspiration and then found it in … well, him. By some sort of osmosis he developed his own hitherto latent artistic talents to the point that he, too, has become a sculptor of some renown. Yet Domingo thinks nothing of artlessly incorporating rusty old bulldozer parts into his studio, an old car seat for those rare moments of repose, a cracked wing mirror for shaving. And then there’s Bernardo, who seems blissfully unaware of any aesthetic paradox in

hanging

a dead goat in the shower to keep off the flies.

However, by odd chance, we happened upon two

like-minded

souls, a handsome young couple called Simon and Victoria, who not only shared our aesthetic vision of optimising the simple beauty of the landscape but carried it several steps further. They had just married when they arrived in our lives, and were on honeymoon, having chosen rather unaccountably to spend it camping in the desert of Almería. On one night and one night only in the

last thousand years has it snowed in the desert of Almería, and it happened to be the very night that Simon and Vicky pitched their tent. The snow flurried in, driven by a howling gale through the flaps of their flimsy tent, nearly freezing them to death. The next night they put up at a little hotel in the High Alpujarra, in Bérchules. In their room was a guidebook with an advertisement for our holiday cottage. It was the only advertisement in the book and, curiously enough, in about five years Simon and Victoria were the only people who ever replied to it.

So they came to stay for a few days to thaw out and, in the inevitable way of these things, ended up living with us for eighteen months. They were the perfect guests: we adored them and they seemed to like us too, and we all became part of each other’s family. They had an

unconventional

way of making a living: they were designers and constructors of aquariums – not little fish tanks but

colossal

municipal affairs full of sharks and rays and barracuda and sunfish. The business of building aquariums is

somewhat

unpredictable and you are often left hanging on for months while the promoters in various parts of the world get the finance together. Which accounted for them having the time to live with us.

Simon is a brilliant draughtsman, designer and

constructor

, and always has to have some project to amuse him. One day, about a month into their stay, he sidled up to me when Ana was out of hearing. ‘Have you ever given any thought to the idea of green rooves for El Valero?’ he asked.

‘Scarcely a day passes, Simon, scarcely a day. Tell me more.’ I was all ears, and for an hour or more we retired into deep confabulation. Occasionally Ana would appear, and we would fall into an unnatural silence, or pretend to

be talking about something that we were not really talking about at all.

A recent plan I had devised for building a new bathroom out of straw bales had come adrift after Ana discovered it meant knocking a great hole in our existing bathroom wall. She and Chloé had taken exception to the idea that passing strangers might take advantage and wander in. I feared that the grass roof idea might fall on similarly stony ground, so to speak, but in fact I needn’t have worried. What Ana likes best, apart from animals – and perhaps Chloé and me – is plants, and so she found the idea of a carpet of plants providing insulation for the house pretty appealing.

Simon’s green roof seemed a logical step for us. Already the walls of the house are so covered in ivy and wisteria that the sun barely touches them at all in summer, and this makes a spectacular difference to the temperature inside the house. With an extra layer of vegetation on the roof, we would be cool in summer and warm in winter – as

cucumbers

and toast – for no running cost at all. These, too, were powerful considerations for Ana.

The dyed-in-the-wool Manolo took a little more

convincing

. When we broke the news to him, he grinned his

broadest

grin and looked from Ana to me and then back to Ana, waiting to see who would crack first and admit that we were ‘taking his hair’, as the Spanish have it. ‘You want to put grass on the roof?’ he repeated incredulously and waited. ‘You mean grass … on the roof?’, he tried again, but still we simply agreed that this was indeed the plan. For days he continued his bewildered refrain of ‘Grass … on the roof?’, breaking off into a chuckle and shake of the head. I’ve no doubt that in the ensuing weeks he drummed up free drinks from Tíjola to Órgiva using just those four hilarious words.

Eager to proceed, we pored over the Internet for details. In Tokyo, Osaka and Kuala Lumpur green rooves were quite the thing, but it turned out that Freiburg in Germany had the most advanced projects, so much of our information came from there and little by little our plans took root.

The first thing we had to do was to properly waterproof and reinforce all the rooves in question by covering them in a layer of steel-mesh-reinforced concrete, then a welded layer of PVC. This detracted somewhat from our green credentials, as PVC is hardly an ecologically sound

material

, but one must be pragmatic. On top of the PVC went another layer of waterproof concrete, then a special felt, like old army blankets, and on top of all that a layer that looked like plastic eggboxes. These held water for a good long period of time. The eggboxes were covered with fine filter cloth and then a deep layer of soil mixed with balls of

arlita

. Simon said the soil should be as inert as possible, for some reason which still escapes me.

Arlita

is exploded balls of clay, like Sugar Puffs: they’re water-retentive and excellent for growing plants, but their main advantage is that they lighten the load. With unadulterated soil you run the risk, when it rains, of the roof becoming waterlogged, the weight being too much for the supporting beams, and the whole shebang crashing into the room below.

The

arlita

came all the way from Barcelona in enormous sacks on the back of a truck and Domingo came down to the river to ferry the sacks across on his tractor. It was clear that he was interested – anything remotely innovative piques his curiosity, but he usually prefers not to show it. That day, however, he asked me a few laconic questions about the project, which for him is akin to wild enthusiasm.

Clearly something was up, but he waited until we had loaded the last batch to fill me in. ‘The papers came through from Madrid yesterday. I’ve bought the farm,’ he said.

It was a simple enough sentence and delivered in the same manner that one might announce the purchase of a new pig. I looked at Domingo, my mouth open in amazement while he grinned sheepishly and traced a pattern in the dirt with the toe of his shoe. ‘Domingo! I had no idea,’ I cried. ‘

¡Enhorabuena

!

Congratulations, I’m delighted.’

And I was. For Domingo was the only farmer in the valley who hadn’t – until this moment – owned his own land, and he was without doubt the most passionate lover of the land. Both he and his father before him had rented their farm for a peppercorn rent from landowners in Madrid who had never even seen the place. For many years he had been trying to negotiate to buy the farm off them, with absolutely no success, but finally he had done it. It was impossible to overestimate just how much a thing like this meant. Country people have an insatiable hunger for land; now at last Domingo could put into practice his own projects for improving his home and the land that surrounded it. I grabbed him and gave him a hug. Someone needed to be emotional about this extraordinary event, and it certainly wasn’t going to be Domingo himself.

The fact that Domingo hadn’t actually derided our scheme with the green rooves, and had even lent a hand with the

arlita

, brought a change of heart in Manolo, who soon made tentative comments that he thought the scheme, though harebrained, might just stand a chance of success.

The insulation and waterproofing layers were complete. Now it was time to plant the roof with drought- and

heat-resistant

plants. This was Ana’s scheme and was inspired by her finding a spectacularly beautiful succulent in the semi-desert of Almería. How any plant could survive such conditions seemed little short of miraculous. Ana identified it as a

Sedum

and set about rooting scores of cuttings in her nursery. She then cast about for other plants that might thrive in the taxing conditions of a flat roof in the Andalucian summer. They included

Mesembrianthemum, Carpobrotus, Crassula

and a whole lot of others that I still don’t know the names of.

Now that the roof is established, lavender, several thymes and alyssum have sown themselves in profusion, and the aerial view of our house has taken on the look of a rather scruffy hanging garden, particularly now that I have sown the roof of the

cámara

, the annexe where we keep our library, with wheat, barley and poppies.