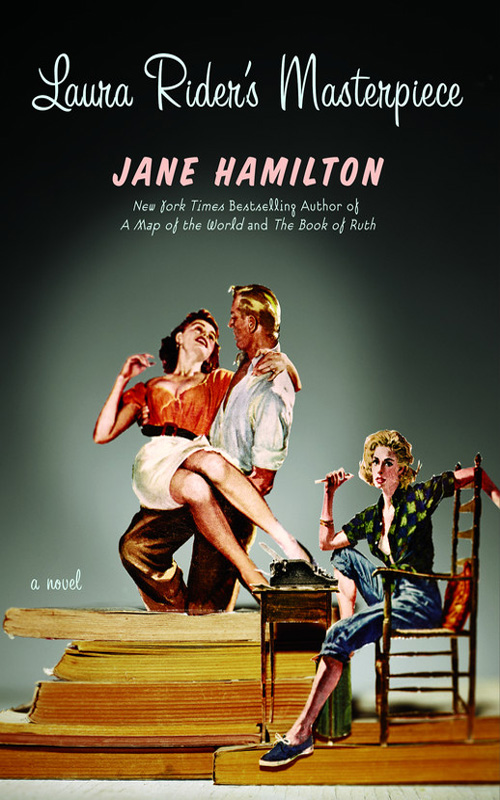

Laura Rider's Masterpiece

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Jenna Faroli would certainly have used Susan A. Clancy’s book

Abducted

and Janice A. Radway’s

Reading the Romance

to learn about persons who have had alien encounters, and about romance readers. I’m indebted to those authors for their

fascinating books. Thanks, as always, to the Ragdale Foundation, and this time, thanks to Mr. Right of the

Isthmus

for the best line.

Copyright © 2009 by Jane Hamilton

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: April 2009

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-55124-3

Contents

Also by Jane Hamilton

When Madeline Was Young

Disobedience

A Map of the World

The Short History of a Prince

The Book of Ruth

For

Dorothy, Gail, and Karen Joy

JUST BECAUSE LAURA RIDER HAD NO CHILDREN DIDN’T

mean her husband was a homosexual, but the people of Hartley, Wisconsin, believed he was, and no babies seemed to them proof.

They also could tell by his heavy-lidded eyes that were sweetly tapered, his thick dark lashes, his corkscrew curls, his skinny

legs and the springy walk, and the fact that he often looked dreamily off in thought, as if he were trying to see over the

rainbow. In the municipal chambers at a public meeting, a town councilman had once said that Charlie Rider needed a shot of

testosterone. It was a mystery to Laura that in Hartley, population thirty-seven hundred, people who had never been to a gay-pride

parade or seen any cake boys that they knew of outside of TV actors, were so sure about Charlie. She assumed that, like any

place, the town was laced with fairies, not visible to the naked eye, but Charlie, she could testify, was not one of them.

Laura herself had not been to a pride parade, but her personal experience included her flamboyant uncle Will, her outrageous

cousin Stephen, her theatrical playfellow Bubby from the old neighborhood, and also Cousin Angie, who had tried to shock them

all by having a lesbian phase in college. No one in the family, it turned out, cared.

Mrs. Charles Rider was the one qualified to set the residents straight about her husband, not because of her expertise with

her various beloved queens, but because of her long life so far with the man himself. Make no mistake, Laura would have liked

to say, Charlie Rider was crazy about women. Charlie was not squeamish. Charlie, if they must know, worshipped the pudendum.

She wanted to lambaste the town, to tell them that the cruelty he had endured through his school years had been grossly misplaced.

In the bedroom he was not only at the ready, always, he was tender, appreciative, unabashed, and, incidentally, flexible.

A night with Charlie was equivalent, both for burning calories and in the matter of muscle groups, to doing the complete regime

of the Bowflex Home Gym. Charlie emphatically was not fag, swisher, fembo, Miss Nancy, chum chum, or any of the other names

he’d been called since second grade. It had always impressed Laura that a town that thought it had so few gays had so many

labels for the aberration that was supposedly her husband.

The real problem was that, after twelve years of marriage, Laura had become permanently tired of his enthusiasm. She’d realized

that if you gave an inch you were in for the mile, that if you were even occasionally available he assumed the welcome mat

was always on the stoop. She disliked the whole charade of fatigue or preoccupation, but she hated, too, how the pressure

of his need had jumbled not only her body but her brain. She was losing her mind, losing her ability to stay focused and organized.

When he hung around her study after dinner, when his sighs seemed to blow through the house, she knew she’d have to give up

her beautiful, well-thought-out plan for a productive evening. And for what? Come morning, there he’d be, eyeball to her eyeball,

fresh, apparently, as a daisy, as if months, not hours, had passed since the last full-body slimnastic routine.

Both before and after she’d quit sleeping with him, she’d read articles and books about sexual fatigue. There were features

in women’s magazines, often with photographs of bombed-out wives, shoulders sagging, bags under the eyes, sitting on perfectly

made beds. Laura understood that she was among millions, that she was another casualty in what was clearly a national epidemic.

She had explained it to Charlie as kindly as she could, saying that, just as a horse has a finite number of jumps in her,

so Laura had used up her quota.

“No more jumping?” he said. “Not ever?”

“I can’t,” Laura said. “I love you, but I can’t.”

“What if we take down a few of the fences on the course? Lower the bars? Shorten the moat by the boxwoods? How—how about trying

a—”

“I’m sorry,” Laura said, and in the moment she did feel a little rueful. “Charlie, I am sorry, but can’t you see? I’m out

to pasture.”

Her secret fear about this new phase of their life was that, without his one superb talent, which, she granted, had given

her hours of pleasure and even, she would say, fulfillment—without that contribution to the household, she wondered if he

actually had all that much else to offer, if he would prove to be worthless. What a terrible thought! She didn’t mean it.

But might he be like a quarterback who, once retired, didn’t have the smarts to buy a restaurant chain or a fitness club?

When such ideas, unpoliced, crept up on her, she strenuously defended Charlie to herself. He had a multitude of virtues: his

help to her in their business, his sunny nature, his ability to make jokes about catastrophes, his flights of fancy, and the

fact that when they made up stories together about, for instance, their own cats, they were so united in their invention it

was as if they inhabited the same brain.

Aside from the Riders’ separate bedrooms, there were several details about Laura that the people of Hartley would have thought

they had no need to consider. They knew she was artistic with plants, but landscape and horticulture were subjects they believed

a girl could learn about by looking at seed catalogues. They did not know that she had lived with her sister for a year, and

nearly every day gone to the University Library to study garden books. Also, she read novels, a habit none of her friends,

and no one in the family, shared. It was a quirk her sisters would think was an affectation—Laura, the community-college dropout,

trying to show off. It was because of this imagined censure on Laura’s part that she was sensitive about—and, indeed, embarrassed

by her hobby. No one knew that she had read every single one of the TV Book Club novels; that is to say, she read them all

until the format changed, until the show featured only dead authors. Laura had stopped cold the summer the nation of viewers

were to read three books by William Faulkner. She quit after thirty pages of the first for reasons she believed that anyone

interested in a comprehensible story-line could understand.

In addition to her secret pleasure in reading, Laura enjoyed writing. Nothing serious or big or personal, no journal stuffed

between the mattresses, no shoe box filled with smudged pages,

no amazing blog that had made her famous in cyberspace. She was satisfied with a small stage, and had nearly enough bliss

using her talents to take care of the correspondence for the landscape business she and Charlie owned. She prided herself

on the connections she made with her customers through her e-mails and the newsletters, communications that were general and

at the same time, it seemed to her, confiding.

It is to my great surprise that my delphiniums still keep coming up, year after year

. This method of relationship was far more gratifying to her than speaking by phone or in person. For one thing, she was an

entirely different Laura on the screen; she liked herself far better in print. It was curious, that she was so much more interesting

and witty and sure when no other human being was present, when the correspondent was nothing but an idea. She wondered what

it meant, that she could only be her ultimate self when she was alone.

“Shhhhh,” she’d begin like a prayer when she entertained her most private fantasy, a vision, a gauzy thing she had never mentioned

to anyone. Where she used to fantasize about certain professional men and also about getting a collie, this innermost dream

did not flicker, did not fade. The strength of her yearning for it had only grown as the years passed. She would lie on her

bed in the spare room where she slept, and close her eyes, and she’d see herself sitting in a wing chair in a long pale skirt,

and a cashmere cardigan lightly studded with moth holes. Charlie would say, if she had ever told him, that she was having

a past-life experience, a life in which she did not, with utmost care, seal away her sweaters in the cedar chest. In her vision

there was usually a cup of tea on the table, and a burning cigarette in a flowered china ashtray, not that she had ever really

smoked. How could she describe this castle in the air to anyone? How could she explain how comforting this abiding image was

to her? She saw herself being still and thinking. That was it; that was the fantasy. Although she did not know anyone who

was a reader, although she’d spent her childhood watching television, and now Nick at Nite was often on until midnight in

the Rider house, Laura wanted, in a dress that came to her ankles and in robin’s-egg-blue high-heeled leather Mary Janes,

to be an author.

The first time the dream took on real shape, the first time there was an object in her mind’s eye, a material thing, pages

wrapped in a rose-colored dust jacket, soft and dense as velvet, was the evening she not only met, but spoke to Jenna Faroli

in the basement of the Hartley Public Library. Jenna Faroli! The host of the Milwaukee Public Radio

Jenna Faroli Show

. Jenna Faroli, the single famous person in the town of Hartley, not counting Tom Lawler, who’d been voted off after three

episodes of

Survivor

; a Mrs. America contestant; and a grandmother who had raised marijuana for her grandson, a dowager who had had to serve time.

Jenna Faroli’s husband, Frank Voden, was a judge on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and though he was prominent, certainly, and

important, no one would have cared about him if he hadn’t had his lustrous wife. The pair had recently moved to Hartley, midway

between Frank’s court in Madison and the radio station in Milwaukee, in an effort to secure privacy and quiet. Hartley residents

tended to be conservative, and yet Laura had noticed a bragging tone in their complaints about the judge. Charlie, in a flash

of wisdom, had explained this by saying that the Faroli-Vodens, even if they were leftist fucknuts, were now Hartley’s own.

Whatever people thought of Frank Voden was of little interest to Laura. Jenna Faroli, she was sure, was universally loved

by her listeners. Because to listen to Jenna was to love her. There were subtle noises she made when she was speaking—nothing

as vulgar as lip smacking, but rather, what sounded like the softest parting of her lips, such delicately made plosives. You

could hear her smile, the creases of it; you could hear how she must be leaning toward her guest if he was in the studio;

you could hear the sweet urgency of her curiosity. She was an intellectual, someone with range, someone with breadth of knowledge.

One morning she might talk with Jane Goodall, and the next a potentially dull person like Alan Greenspan, and the day after,

David Bowie. She was able to make even the Federal Reserve interesting, because she knew that somewhere deep within every

subject was the land mine of human relations. Laura had analyzed Jenna’s method and had concluded that Jenna could find the

story in any topic because she understood that there was no such thing as happiness in the middle of the narrative.

Narrative

, as a matter of fact, was a word that Laura had learned from the great JF. It didn’t matter if she was interviewing Sharon

Stone or a half-dead senator, or a doctor specializing in cancer of the gums, or the man who had caught the largest fish in

the state of Wisconsin. Jenna Faroli seemed able to see into anyone’s life and so ask questions that articulated a problem

the guest might not even know he had. For some time, she had not been a household name outside of Milwaukee Public Radio’s

fame, outside of that small circle of the brainy, but five or so years before, the show had been syndicated, and Jenna Faroli’s

voice now rippled out into the nation.