Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast (9 page)

Read Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast Online

Authors: Edmond Boudreaux Jr.

CHAPTER 12

D'I

BERVILLE AND THE

O

POSSUM

Today we take for granted that we will not encounter any animal life that we have not seen, heard of or read about. But in contrast, when the French were exploring the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast, they did not know what they might run into, be it man or beast. One of the most interesting encounters occurred when French explorer Pierre Lemoyne d'Iberville was visiting the village of the Bayogoulas on the Mississippi River.

On March 14, 1699, the chief of the Bayogoulas took d'Iberville to the tribe's temple, where d'Iberville noted that there were several clay figures of animals. These clay effigies were created in the likeness of bears, wolves, birds and one animal d'Iberville had not seen in France or his native Canada. He sent his men with some of the Bayogoulas to hunt down and shoot some of these strange animals. After a successful hunt, they returned with eight of the animals. On examining the eight, d'Iberville described them as having “a head like a suckling pig's and as big, hair like a badger's, gray and white, a tail like a rat's, paws like a monkey's, and under the belly has a pouch in which it generates its young and suckles them.” The Indian call this animal

choucouacha

, but today we know it as the opossum.

The opossum is the only marsupial in the United States. Marsupials are mammals that raise their young in pouchs. Today, opossums live in an area that extends from southern Canada to Central America. They live in fields, forests, mountains and in most habitats except deserts. They like open woodlands along streams.

A reenactor portrays Pierre Lemoyne d'Iberville, the French explorer of the Northern Gulf Coast.

Edmond Boudreaux

.

We do not know the range of the opossums during the French Colonial period, but we do know that d'Iberville and his men were mostly native Canadians who had evidently never seen opossums before exploring Mississippi's Golden Gulf Coast.

CHAPTER 13

D'I

BERVILLE

'

S

C

ANNONS

In the Biloxi war memorials north of the Small Craft Harbor sit four ancient cannons. Weathered by time and hurricanes that have caused the metal to corrode, these four 1700s cannons are a little out of place sitting in the midst of World War I and World War II markers and artifacts. They have been painted black to help slow down the corrosion and preserve them.

Most locals know them as the d'Iberville cannons. The d'Iberville cannons were pulled from a watery tomb of a sunken vessel located near the eastern shore of Biloxi Bay. Folks who were familiar with them assumed they were lost in Hurricane Katrina, but they sit with their barrels pointing to the Mississippi Sound. Below the cannons is a plaque with the following inscription:

Cannons from unknown French or Spanish ship sunk in the Bay of Biloxi shortly after the establishment of the first capitol of the vast province of French Louisiana at Biloxi in 1699. Donated to the City of Biloxi as a memorial to the Tiblier Family by Captain Eugene Tiblier II who discovered the sunken boat in 1893

.

The story of the cannons was first reported in the

Biloxi Herald

in September 1892. Titled “A Mysterious Find,” the newspaper article focused on a “rock pile,” which was actually an oyster reef on the east side of Biloxi Bay near Fort Point Ocean Springs. It seems that the oyster reef had formed over the wreck of an old ship that had supposedly lain under the water for nearly two centuries.

The article stated that about a month previously, oysterman Eugene Tiblier II, while working the reef, encountered a hard object. After striking the object three times, he decided to enter the water and investigate the object. What he discovered was a cannon, and he at once notified his father, Eugene Sr. The father and son, with the help of Captain Jose Suarez on his schooner

Maggie

, secured the find. For the next twelve days, they worked on the site and realized that it was indeed a sunken vessel. The assumption was that the vessel was a warship from the French Colonial period.

As work continued, four iron cannons were recovered. One was six feet long, with a muzzle of eight and a half inches and in fair condition. The article stated that letters “H.E. or F.O.S.” could be seen on the cannon about one foot from the touch hole. Additional work brought a seven-foot cannon to the surface. The cannon had no markings, but part of the gun carriage was still attached. The two other cannons were four feet long and had two-and-a-half-inch muzzles but were in poor condition. Additionally, numerous cannon balls of two, two and a half and three inches, as well as parts of gun carriages, were recovered. Rope was also recovered but began to dissolve into dust after it was exposed to the air. The wooden vessels contained a treasure-trove of artifacts.

The paper reported that the artifacts recovered confirmed that the wreck was very old. The vessel was believed to be sixty-five feet long and twenty feet wide. It was reported that the vessel's wooden timbers were oak and mahogany, and the wood was held together entirely by wooden pegs. The article reiterated that no nails or metal pieces were found holding the wood together. The wood had been under the mud, which helped keep it in a good state of preservation. There were a large number of stones in the wreck. These were mostly ballast stones that went down with the vessel. The vessel sat in about twelve feet of water at high tide.

Among the artifacts were bricks that were discovered in the wreck. The bricks were described as being about one and three-eighths inches thick, eight inches long and four inches wide. The writer indicated that the bricks were different from those used in 1892 and fit the description of French Colonial bricks found along the coast.

The iron works that were recovered had copper bolts, a wooden sheave (pulley) and a block eye. These items were described as being made of wood different from the wood typically used in 1892. Due to size of some of the artifacts found, it was assumed that the vessel was of considerable size.

The d'Iberville cannons are shown in front of the Biloxi Community Center in the 1950s.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

In addition to the cannons, the salvage operation had recovered gunpowder, a scabbard from an officer's sword, a bung stopper from one of the water casks, pulleys, block eyes, muskets with old-fashioned locks and much more. The gunpowder was found in large chunks but retained its peculiar smell. Supposedly the Tiblier family loaded the powder and a cannonball into a cannon that was tied to a tree. Upon firing, some of the windows in the Tiblier house shattered.

The newspaper article concluded by stating that nothing could be learned of the history of the vessel. All of the older inhabitants knew it only as a rock pile and an oyster reef. Due to the artifacts that had been brought to the surface, it was surmised that the vessel was either one of d'Iberville's French vessels or a Spanish vessel, though some individuals believed it to be a pirate ship lost in a storm.

The Tiblier residence was located in the St. Martin community, just west of Bayou Porteaux. Between 1892 and 1905, the artifacts lay exposed around the Tiblier property. Stories indicate that cannonballs, copper pots, old muskets, swords, copper utensils and hunks of wood decorated the yard. Many individuals visited the Tiblier home to see the artifacts. There are stories that Eugene Tiblier freely gave some visitors artifacts as souvenirs. Finally, only the four cannons remained.

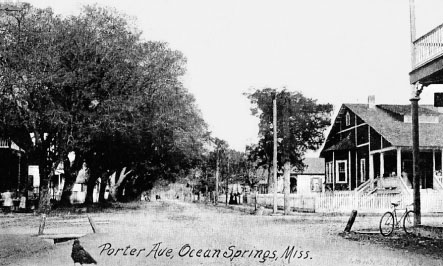

Porter Avenue Ocean Springs.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

The Tiblier family eventually moved to Holly Street in Biloxi. During the early 1900s, the four cannons were set in a single concrete foundation. Finally the cannons were donated to the City of Biloxi. The cannons were placed in front of the old Biloxi Community Center on Biloxi Beach Boulevard. This location became the cannons' abode. Even when the Santa Maria Del Mar Apartments were built at this location, the cannons remained as lawn fixtures. The d'Iberville cannons have since been relocated to the south side of Highway 90 to the Biloxi's War Memorial Park grounds, north of the Small Craft Harbor.

After the early 1900s, the sunken vessel continued to lie undisturbed in its watery tomb. During the 1980s, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History authorized magnetometer readings of the area. The magnetometer measures the intensity of a magnetic field. The readings showed several anomalies in this area, and it was recommended that the area should be researched. In 1999, side-scanning sonar was used to relocate the vessel. This resulted in a series of archaeological dives on the wreck. The underwater archaeologists determined that a portion of the vessel on both sides of the keel was still intact. They also removed wood samples and other artifacts that indicated that the vessel was definitely an early 1700s ship.

Early French records indicate some French vessels were lost at Biloxi Bay. In 1700, a small supply smack loaded with goods and gunpowder accidentally caught fire near Fort Maurepas. Since the vessel was loaded with gunpowder, it was set adrift and, of course, exploded and sank. In 1717, a severe hurricane tore Dauphin Island into two sections, and many vessels were lost. Then in September 1722, another severe hurricane caused widespread destruction from Biloxi to Louisiana. A large French supply vessel was lost in Biloxi Bay, near the site of Fort Maurepas. Its cargo was artillery, lead and meats. There is a strong possibility that this is the vessel in question resting in Biloxi Bay. Hopefully in our near future, the vessel will be raised from its watery tomb and positively identified, but for now, it will remain a mystery in its resting place in Biloxi Bay.

CHAPTER 14

L

ETTER FROM

C

AT

I

SLAND

The Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans took place on January 8, 1815. It would be the last battle of the War of 1812 and important in gaining worldwide respect for our country. Many are familiar with the outcome and the fact that Andrew Jackson became a popular person of the time. Most of what is known comes from the American point of view. In 1917, a letter came to light written by British officer C.J. Forbes on January 28, 1815, while on board HMS

Alcestis

off Cat Island. It was published in the

Times-Picayune

on January 7, 1917.

C.J. Forbes's daughter Miss Forbes of Santa Cruz, California, found the letter and presented it to Dr. Jerome B. Thomas of Palo Alto. He in turn gave the letter to Professor Ephraim D. Adams of Stanford University, who presented it to the Historical Society of East and West Baton Rouge. Of course, we do not know if this was a copy of the original or the original. Either way, the letter shows a British officer's view of the Battle of New Orleans.

The British were positive they would be successful in New Orleans. They were so certain that they had a large group of administrators and officers' wives with them, along with the invading forces of Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane. Vice Admiral Cochrane had finished operations in the Chesapeake that included the burning of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. Vice Admiral Cochrane's original plan was to go overland to New Orleans. He hoped to land his forces in Pensacola. After arriving at Pensacola, he realized the Spanish at Pensacola were expecting an invasion from Andrew Jackson and his American forces.