LEGO (17 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

When I started building with LEGO bricks again, I never realized there were so many things you needed to do outside of snapping pieces together. There is sorting and storing and planning and drawing. And now, photographing. At some point, building seems to be the reward for doing all of these other tasks. I have heard adult enthusiasts say that it seems as if they never get to build anymore. I’ve only just started, and I’m not building nearly as much as I thought I would.

11

The Stranger Side of Building

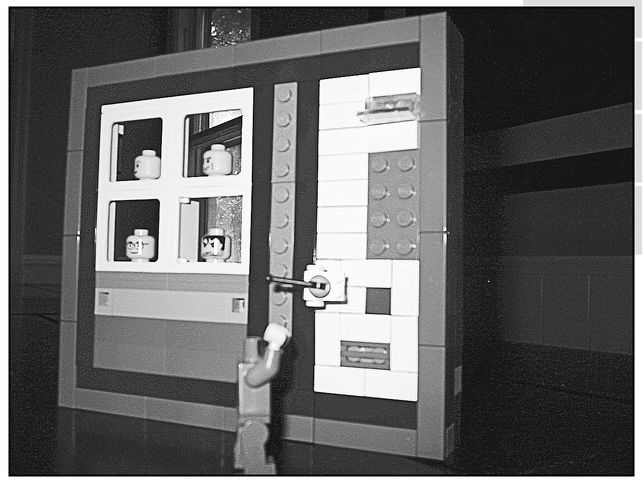

The prototype for my LEGO vending machine, which offers up a variety of head options for those minifigs in need of a new look.

Early one night after the calendar has turned to September, I head into our third bedroom and grab my suitcase to pack for Brick Show in Bellaire, Ohio. Instead of preparing this room for a baby, I’ve been stacking more bins of LEGO on the floor. My foot sends a small rectangular box skidding across the room—a World of Mosaics set I picked up for a dollar at the liquidation of a secondhand shop. The slow takeover of the bedroom carpet makes me feel empty. These are supposed to be my kid’s toys, not mine.

Out of the corner of my eye, I notice the MTT Trade Federation sitting up against the opposite wall.

Today’s the day,

I tell myself. But I don’t even crack the box. The Star Wars set is turning me back into a middle school kid, putting off making that phone call to a girl I like. I remember staring at the clock, the phone in my hand as I sat on my beanbag that looked like a soccer ball.

Just five more minutes. I’ll call at 7 p.m. Okay, at the end of

Duck Tales.

7:30 p.m. goes by.

I was like a nervous snooze button.

Today’s the day,

I tell myself. But I don’t even crack the box. The Star Wars set is turning me back into a middle school kid, putting off making that phone call to a girl I like. I remember staring at the clock, the phone in my hand as I sat on my beanbag that looked like a soccer ball.

Just five more minutes. I’ll call at 7 p.m. Okay, at the end of

Duck Tales.

7:30 p.m. goes by.

I was like a nervous snooze button.

My inaction is not surprising, considering all of the things that remain unsaid between Kate and me. The room is pregnant with all of the topics that we’re not talking about: sex and creation chief among them. I mistakenly think the world of adult fans is free of sex, forgetting that sexual intercourse was the most interesting thing to talk about in middle school, and still is to most grown men. So, even when trying to avoid it, I’m stuck focusing on sex and creation.

Time plus a culture of men acting like boys always produce one guaranteed outcome: penis jokes. Some 99.9 percent of the LEGO creations I find online are not adult content, despite the ages of the builders. But out on the fringes, I stumble across a dirty space subtheme, Bonktron, which popped up on LUGNET in 2005.

“The Bonktrons are a hedonistic cult devoted to nothing but the peasures [sic] of the flesh.... They were originally part of the Classic Space regime, but found their philosophies too prudish and departed the more populated regions of space to found their own colony,” wrote Australian AFOL Allister McLaren in his September 2005 post introducing the fad.

The first Bonktron spacecraft, classified as “a deep penetration recon ship,” was called the “Throbtastic Jismatron X3.” It was an absurdly phallic spaceship, constructed primarily in tan with a red tulip-shaped nose cone. The idea of turning LEGO bricks into a naughty MOC wasn’t a new one—Brickfest 2004 featured a gray Viagra Moonbase with an extendable corridor—this was just the first time that such a theme had been posted online. Over the next two months, a long white rocket—the Long Range Obliteration Vehicle (Experimental), or L.O.V.E. rocket—and the Millennium Phallis were uploaded to LUGNET The ships tended to feature a disturbing number of minifigs with bare chests and mustaches.

Like all penis jokes, this one gets less funny with repetition. Bonktron creations were quickly banned from

Classic-space.com

; the Web forum for LEGO space enthusiasts apparently was too prudish. By 2006, “Bonktron” was merely an adjective to describe a spaceship with a form that was a bit too familiar, another way to tease a fellow builder.

Classic-space.com

; the Web forum for LEGO space enthusiasts apparently was too prudish. By 2006, “Bonktron” was merely an adjective to describe a spaceship with a form that was a bit too familiar, another way to tease a fellow builder.

But that doesn’t mean that crude representations of LEGO pornography don’t exist. The pizza delivery guy and sleepover party motif can be found all too easily online. YouTube pulls up 825 videos when you search for “LEGO porn,” most of which are stop-motion animation involving LEGO minifigures. Whereas Bonktron is a bit cartoony and involves some actual building skills, watching a minifigure in a simulated sex act is just uncomfortable. It belongs in the category of places we

can

go, but don’t

need to

as a society.

can

go, but don’t

need to

as a society.

In policing itself, the AFOL community has set up standards and often has been the first to criticize creations that could negatively impact the family-friendly image of LEGO. The rules are simple: no booze, no sex, and no drugs. It seems there is an unspoken agreement that AFOLs will build in this kid’s version of the real world. But you can find hidden touches and jokes: a roof that reveals beers in a cooler, minifigs in compromising positions behind a castle wall.

Still, adult fans can’t control the entire Internet, and despite LEGO’s careful control in selecting partners, bricks will sometimes appear in unseemly situations. In fact, the fifty years that the company spent imbuing the plastic bricks with the values of childhood play and imagination were likely the reason that the Polish artist Zbigniew Libera approached LEGO in 1996 seeking a donation of bricks for an undefined art project.

LEGO provided the bricks, and Libera shocked the company, as well as the world, by creating sets that mimicked concentration camps and torture scenes from the Holocaust. One box featured a LEGO skeleton being beaten by a prison guard; another showed five skeletons being marched into a facility surrounded by barbed wire. The boxes for the seven sets included safety warnings and the words: “The work of Zbigniew Libera has been sponsored by LEGO SYSTEM.” LEGO responded immediately that it had not sponsored the work, in an effort to defuse the public relations nightmare.

“If we had known before what he was going to do, we never would have given him the bricks. But we talked about it and decided [that] to make a big thing about it now would only draw more attention,” said Peter Ambeck-Madsen, LEGO’s director of public relations.

The concentration camp sets were part of a series of creations by Libera, which he called “Correcting Devices,” designed to show the difference between the world marketed to children and the world that actually exists. Libera, who also modified Barbie dolls to make commentaries on aging and beauty, sought to translate the horrors of the world into a language that children could understand by depicting them through toys. But kids weren’t the only ones affected; many adults were horrified by Libera’s work, by seeing a toy they associated with their childhood used in such a light.

Our plastic brick creations become reflections of our values or perversions. I don’t like LEGO porn because of how it makes me feel, and the Holocaust sets are wrong because they sully the memory of building with my father. Adult fans want to protect LEGO because they want to protect their own childhoods.

LEGO bricks are not cuddly. They’re sharp and hard to the touch. But our associations are fragile. Those experiences and memories can be played upon, used to imbue inanimate plastic pieces with deeper meaning. Yet a piece of art doesn’t have to be disturbing to have a dramatic impact on our culture. It needs only inspiration—and where better to start than the Old Testament for Brendan Powell Smith, thirty-five, the originator of the Brick Testament, a collection of LEGO vignettes that depict scenes and stories from the Bible.

Brendan is one of the few adult builders who I knew existed before I even started researching the AFOL community. If you’ve ever seen a LEGO Garden of Eden or Noah’s Ark, comic-book panel-style stories with captions under photos of LEGO vignettes, you probably know him, too. He’s written three books in his Brick Testament series:

The Story of Christmas, The Ten Commandments, and Stories from the Book of Genesis.

The Story of Christmas, The Ten Commandments, and Stories from the Book of Genesis.

In the beginning, for Brendan, there was LEGO and religion. The former was his favorite toy while growing up in Boston, and the latter was instilled in him weekly by his mother, who taught Sunday school at their Episcopalian church. But everything changed when Brendan entered the Dark Ages at the age of twelve.

“The LEGO in my house got boxed up and put in basement storage. I also made a conscious decision to try and put aside what seemed to me to be childish ways of thinking.... Though I hadn’t set out to have this process affect my religious beliefs, in the end it did quite profoundly, and the short version of the story is: I found myself being the only atheist I knew in my family or community,” writes Brendan when we exchange e-mails about the Brick Testament.

At Boston College, he studied religion, immersing himself in the Bible. He was searching for an answer to why people were drawn to Christianity.

“Although the Bible is the world’s all-time best-selling book, and millions of people would claim to base their lives and their morality upon it, the vast majority of believers and non-believers alike have never actually read it,” writes Brendan.

If people weren’t going to read the entire Bible, he reasoned, an illustrated work might be a better way to get them to see what was actually inside the pages. In the years after college, Brendan took his childhood LEGO boxes out of storage and began buying sets on eBay.

“As I started constructing a LEGO Garden of Eden, it further occurred to me that this could be the opportunity I’d been looking for to retell the Bible’s stories in ways people would find fun and engaging,” writes Brendan.

He was working as a Web designer in 2001 when he created the first six stories from Genesis and published them online. Here he showed off his wicked sense of humor, and thus the Reverend Brendan Powell Smith was born, a tongue-in-cheek name he discusses in question 10 on the FAQ page of his Web site.

Is he really a reverend?

Most ministers, priests, or other religious clerics would not actually use “The Reverend” before their

own

names, for to do so would be presumptuous and rather vain. The Rev. Brendan Powell Smith is not an ordained member of any earthly church, and is widely regarded as being both highly presumptuous and extremely vain.

own

names, for to do so would be presumptuous and rather vain. The Rev. Brendan Powell Smith is not an ordained member of any earthly church, and is widely regarded as being both highly presumptuous and extremely vain.

The content of the stories was seemingly just as irreverent, with fantastic tales of beheadings, rape, incest, prostitutes, and wrestling with God. However, although at times graphic, the stories were all taken word-for-word from the Bible. The popularity of the site grew over time, leading to a book-publishing deal and Brendan’s decision to work full-time on the Brick Testament. His life in Mountain View, California, is once again about LEGO and religion.

Listening to someone talk about building with LEGO just makes me want to build something with LEGO myself. When I spill out my Pick A Brick cup onto my desk, I notice that I have a lot of 1 × 4 red, white, and green tiles. And next to those tiles is an assortment of minifig heads piled on top of 1 × 2 translucent plates.

I doodle out the rough shape of a vending machine and refine it based on pictures I find online of snack and soda dispensers. I will build a vending machine for LEGO minifig heads, with a headless patron trying to decide on his mood. I want to achieve a smooth surface, so this will be my first attempt at building with the Studs Not On Top (SNOT) technique. The idea is that by changing the orientation of the bricks or plates, you can achieve more detail. In a typical creation, all of the bricks are facing the same direction, usually pointed up. SNOT uses hinges, specialty LEGO elements, or Technic bricks to place bricks at an angle to each other. The builder can then choose whether he wants a studded or a smooth face.

It turns out there are not a lot of studded buildings and cars in real life, so SNOT techniques are needed to help bring LEGO elements together without the studs showing. SNOT also offers the chance to offset LEGO bricks, wherein a row or corner might stick out half the width of a plate in order to simulate the ledge of a window. This technique is known as Studs Not In a Row (SNIR).

I build a four-window vending machine, five inches tall and six inches wide. A gearshift doubles as the change-release button, a 1 × 2 gray grille tile is the coin refund slot, and a 1 × 2 translucent corner piece is the dollar bill accepter. The end result is too square—more of a vending box than a machine—but I like the idea of using SNOT techniques to build. The face of the machine is tiles, with the exception of a 2 × 4 gray brick that I have left exposed to simulate the keypad where you would enter your choice. A headless minifig stands before the buttons to complete the vignette.

I’m satisfied with my creation until I search for LEGO vending machines on the Internet and discover that somebody has made a fully functioning model that accepts coins and vends snacks using Mindstorm motors and sensors. Suddenly I’m back in Operation MindStretch, the fourth grade program for gifted students, trying to build a bridge out of spaghetti that will hold a tennis ball. In the meantime, the guy next to me already has a bridge capable of supporting a six-pack of soda.

Other books

Robbie Forester and the Outlaws of Sherwood Street by Peter Abrahams

A Quarter for a Kiss by Mindy Starns Clark

On Thin Ice by Nancy Krulik

Apricot brandy by Lynn Cesar

Wonder by R. J. Palacio

John Shirley - Wetbones by Unknown

Borrowed Billionaire #5 Set it on Fire by Strong, Mimi

B0089ZO7UC EBOK by Strider, Jez

This Man and Woman by Ivie, Jackie

Destination: Moonbase Alpha by Robert E. Wood