LEGO (19 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

We begin to climb the steps behind the Darth Vader to the second floor, and I ask where Dan finds all the models.

“I’m tracking nine models in the United States and three in Germany. We got a new referee from England, and I’m mad because I just lost out on a Tigger on eBay,” says Dan.

When he bought the two school buildings, Dan had a vision for a LEGO museum, one that would celebrate LEGO as art and display the works of the artists who worked to build LEGO models. And he wanted to fill it with all of the models that the LEGO Group didn’t want or need—those that had been created for limited-time promotions or partnerships and were destined to be recycled or destroyed. In some ways, he was taking his computer recycling business model and applying it to LEGO. He would pick up anything they didn’t want; they just had to tell him where to go. People wouldn’t come to Bellaire to see old monitors or hard drives, but they would want to see the incredible LEGO models he would collect.

“I try to spend money on things that are one-of-a-kind, very neat, or tough to get. I know I ticked off a lot of people on eBay because I picked up a lot of displays that other people wanted to put in their basements. But I want all of it out there for people to enjoy,” says Dan, gesturing to a pair of life-size LEGO men in shiny silver protective suits stirring a metal bucket of red plastic bottle caps in the center of the second-floor hallway.

The museum is essentially one of the world’s largest private collections turned into a display for the public. This is Dan’s escape—an escape from all the jobs that he had to do to get to this point. Here, he can forget about his time working for Microsoft as an IT guy installing Novell 3.12, or running a flea-market food truck. At the top of the stairs is Duane’s white bridge, encased in glass. It’s like seeing an old friend. Behind the bridge, a four-foot-tall Dora the Explorer is posed to look like she’s talking to a similar-size Diego beside a bank of old red school lockers.

“LEGO made Dora the Explorer sets? How did she end up here?” I ask.

“Yeah, back in 2004, I think. I’m not sure how exactly they ended up here. We just got two large wooden crates on our front doorstep one day addressed to us,” says Dan.

He walks through the nearest door, and I follow. We’re in the Zoo Room, where LEGO animal models have been placed in a series of wooden-frame cages wrapped in chicken wire. Across from a LEGO Winnie the Pooh, a LEGO polar bear peers out from beneath a cave built out of cubes covered in fluffy white material, as two penguins stand on ice floes. A large white cow, the kind featured in art series in Chicago and Kansas City, is against a bank of windows, the ceramic covered in Scala and LEGO accessories.

“Basically, we try to create a theme in each room, and I think it kind of worked out. This one turned out great,” says Dan, putting his hand on the side of the cow.

The exhibits are a bit like oversize dioramas. It’s difficult to reconcile thousands of dollars’ worth of models inside obviously hand-built displays. But how do you judge the quality of somebody else’s dream? I don’t want to be callous, and the organization feels right—a loose homage to the themes of LEGO sets.

“What do you say to people who just think this is about you?” I ask him, noticing a blue Chupacabra LEGO model in the corner on a bale of hay.

“I don’t want this to be just my opinion. That’s the one problem I have with the museum—right now you’re just seeing me. I don’t want it to just be me, I want everybody else to come and build and make this a community,” says Dan.

I believe that he wants to share the models with as many people as possible; but I get the distinct impression that he also wants to be known as the guy who achieved that feat.

On the same side of the hallway as the stairs we walked up are three classrooms also organized by LEGO theme: History, Western, and Mars rooms. The lights are off in the Mars Room, and Dan pauses before we enter.

“Walk in,” he says, a big grin on his face. I step through the doorway and hear Dan smack the wall. “Now, look up.”

A scaled-up two-foot minifig from the Mars Mission theme pops out from the ceiling, the hydraulics behind it making a whooshing noise.

“That’s great.” I laugh, my heart racing from the alien a few feet from my face. We walk into a space-themed room that is lit by blacklights. It’s like being in a dorm room at a fraternity house. Across from a robotic version of the alien minifig is a rectangular glass tank that could be the largest aquarium I’ve ever seen. It’s a traveling display built for Space sets.

“How on earth did you get this?” I ask Dan.

“I wasn’t just getting things from LEGO, I was getting contacts from people that did things for LEGO and were working with the company to make wild stuff. I even made it a point to meet the guys that pack boxes,” says Dan.

This is the side of his personality that likely drove a wedge between him and LEGO. He is opportunistic—a side effect of being a serial entrepreneur. In his drive to acquire models, Dan has worked with LEGO vendors and subcontractors, not all of whom are happy with LEGO. And I’m sure he understands how to play off those feelings.

“I don’t lie,” Dan tells me. A moment later he amends, “I would only lie for something important, like to save somebody’s life.” I believe Dan, but I wonder about his definition of important. The ultimate goal of acquiring more models means that Dan is constantly in deal mode. He always wants more, and he’s not afraid to ask for it.

Yet when he is being earnest, Dan is charming. I can see why people would want to help him. He talks quickly, the words tripping from his lips.

Dan’s drive is what launched the museum; it’s also what made it difficult for him to work within a corporate framework like that of LEGO. Things began to change in the beginning of 2005. Dan was supposed to get surplus brick from the LEGO Outlet store in Dawsonville, Georgia. LEGO’s first retail outlet in the United States, open since 1999, closed on January 22, 2005, but the bricks never arrived. LEGO was still restructuring, trying to manage costs. That July, a 70 percent controlling interest in the four LEGOLAND parks was sold to the Blackstone Group for $460 million. The parks are now run by the Blackstone subsidiary Merlin Entertainments, the same group that operates the Madame Tussauds wax museums.

“I had a ten-year plan, and then Bill retired in 2005 and it was like I never existed,” says Dan.

As LEGO reorganized in order to focus on its core products, it seemed that nobody was really sure what to do with Dan. His contract with LEGO was nonstandard. He’s an authorized LEGO retailer who has never signed a nondisclosure agreement. He was a stud that stuck out a bit too far, and without a mentor like Bill to advocate for him, Dan’s aggressiveness was seen as abrasive by some in the organization.

LEGO’s position is understandable. It’s difficult for a multinational corporation to deal with a single person. With his own ventures, Dan can approve or disapprove everything immediately, while decisions at LEGO need to pass through the proper channels. And even if that process happens relatively quickly, I sense that Dan’s impatience would leave him feeling unsatisfied. It’s not just that Dan is nonstandard, it’s that he believes he should be exempted from the standard rules.

Dan was no longer allowed to use the LEGO name in promotions, and the future of the museum seemed uncertain. The opening date got pushed back to 2006. Dan began unpacking models on February 11, wearing three layers to keep out the chill in the unheated school. However, he still had a relationship with LEGO. On the way back home from his twentieth high school reunion in upstate New York, he stopped at LEGO’s U.S. headquarters in Enfield, Connecticut. He and his son Conrad drove back to Ohio with a rented Penske truck full of new models for the museum, including a scaled-up minifigure in a helicopter and a Mars Mission spacecraft.

The carpet leading to the museum basement is dark blue with a repeating pattern of LEGO bricks—old carpet from LEGO corporate headquarters. As the lights flicker on, I think I see another person. But it’s actually a life-size replica of NBA player Dirk Nowitzki wearing a Big Red jersey, the local nickname for the Bellaire High School sports program. Next to Dirk, a LEGO goat wearing a red “Lifeguard” shirt sits atop a lifeguard’s tower with a whistle in his mouth.

“At one point, LEGO knew where every model was. They had serial numbers on plates, but not since they’ve started to be mass-produced. They’re scared of it ending up in a porn shop or things like that. But the lifeguard, I just got it from a topless club down in Georgia. So, it was already happening. The worst-case scenarios were already happening where liability could be an issue,” says Dan.

The goat model is a perfect illustration of the complicated relationship between Dan and the company. Dan rescued the goat lifeguard from a non-family-friendly environment in order to display it in his museum. It’s the kind of move that LEGO has historically done, taking a model out of public circulation to protect its corporate image. Yet the defender of the brand has trouble getting a meeting.

“We’re half a world apart and they won’t talk to me,” says Dan as we sit on the school’s bleachers, “but as someone at LEGO has told me, just because they like you, doesn’t mean you have all the levels of approval for what you’re trying to do.”

It also doesn’t help that Dan can’t keep himself from testing the boundaries. In August 2007, as he was getting ready to unveil his museum to the world, LEGO approached.

“They called and said not only can you not use our name, but you can’t be open. It’s four years later and we’re dealing with this stuff all over again,” says Dan.

He removed the words “LEGO® Store” from the planned sign out front, and the museum was allowed to open.

Dan wanted something that he felt would immediately put the museum on the map. He has saved his favorite part of the tour for last. In the former gymnasium, a massive forty-four-foot LEGO mosaic of a semitrailer covers the former basketball court. He’s not sure exactly how many bricks are in the construction that covers the length of the gym floor, but it’s at least 1.2 million studs. More than 250 children each contributed a square to the mosaic during the first Brick Show.

“LEGO didn’t like the idea that I had a Guinness World Record, but if they ever try and do better, I’ll just move the tractor trailer over and add more to the trailer,” says Dan.

Guinness certified the mosaic build from the first Brick Show as the largest LEGO image in the world, measuring 80.84 square meters (870.15 square feet).

“Now I’ve got my claim to fame, but where do I go from breaking the world record? I have always wanted to do Yellow Castle,” says Dan, flexing his fingers, which have tightened up from building.

Guinness will not be coming to Bellaire to verify the build, because it is not an official LEGO category. But for Dan, the idea of gathering people together is what is important. In the middle of discussing the mosaic, he remembers why he walked me down to the basement. He goes behind the bleachers to a control panel that is next to a wheelchair lift. The stage lights suddenly begin flashing in primary colors. On the stage is a three-piece robotic LEGO band, Plastica, that used to be a showpiece at FAO Schwarz in New York City. When Dan tracked it down, it was in a ceiling storage space at the Yankee Candle headquarters in South Deerfield, Massachusetts. One robot mimics playing the drums while another moves his guitar. The lead robot singer begins singing in a futuristic voice their signature song, “Just Imagine.”

In the basement of the former Gravel Hill School, I’m watching $62,000 worth of robotics play a made-up song just for me. This is the real LEGO museum. I forget about the paint peeling in the corners and the fact that I feel as if I’m inside someone else’s dream. I am stunningly happy. I can’t find the words, but Dan does.

“It just”—he pauses—“it’s just really fun. I went from this lifestyle where everyone was pissed off all the time. I was a cubicle technician, running into people that were at the end of the world.”

The robots abruptly cut off in the middle; a circuit breaker has been tripped. Dan adds it to the list of things he will need to fix before the convention on Saturday—another item in the long list of adult responsibilities. The quiet is jarring and the moment is over. Dan has to leave to pick up Breann, but he checks in with his wife, Carol, before leaving. She’s still sorting minifig castle weapons.

“I didn’t know she could build until two weeks ago, and I’ve known her for twenty years,” says Dan, grabbing his jacket by the door.

“So it’s got you hooked too?” I ask Carol. I’m curious to find out what the woman married to Dan thinks of the museum.

“What I told him then and I told him now, I don’t have to like LEGO to like you,” says Carol.

She tells me the story of meeting Dan over two decades ago, when her sister invited him to their house for a game of Dungeons & Dragons.

“He came to the door with his cute kind of duck walk, and I wondered, who is that?” says Carol.

Theirs is a love story, not a LEGO love story. The game started, and it was then that Carol truly noticed Dan.

“When we were playing, he was always looking for a way to have fun inside the game. He didn’t play like anyone I had ever met,” says Carol.

I agree with her. Dan doesn’t play like anyone I’ve ever met either.

13

It’s Okay, I Work Here

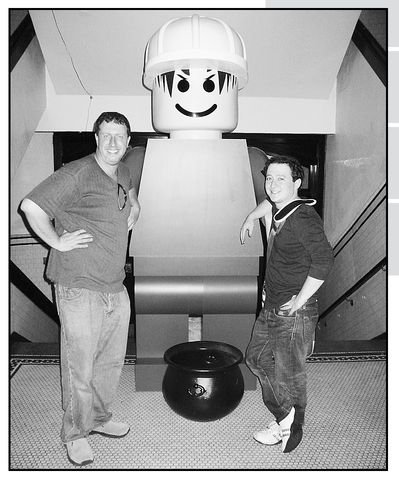

Dan Brown (left) and I pose with a maxifig—an eight-foot, scaled-up version of a minifig—in the stairwell at the Toy and Plastic Brick Museum.

Other books

Santa Hunk by Mortensen, Kirsten

The Friday Society by Adrienne Kress

Horizon (03) by Sophie Littlefield

The Calamity Café by Gayle Leeson

Merkaba, a supernatural suspense series (Walk the Right Road, Book 3) by Eckhart, Lorhainne

Survivor: Steel Jockeys MC by Glass, Evelyn

Fight For You by Evans, J. C.

Whistling in the Dark by Tamara Allen

Dying to Tell by T. J. O'Connor

Extra Innings by Doris Grumbach