Leonardo and the Last Supper (26 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

A possible self-portrait of Leonardo on a page of his

Codex on the Flight of Birds

The most famous of all Leonardo portraits is the supposed self-portrait of an old man in red chalk, beneath which some unknown person later inscribed in black, now barely legible: “

Ritratto di se stesso assai vecchio

” (Portrait of himself in fairly old age). The cataracts of hair and beard feature again, though Leonardo—if it is indeed him—now appears beetle browed, bald on top, and considerably older. Only discovered in 1840, the drawing was widely accepted in the nineteenth century (and still is by many today) as Leonardo’s self-portrait. However, it is now believed to date from the 1490s, from around the time, in fact, that Leonardo painted

The Last Supper

. If this dating is accurate, the drawing cannot possibly be a self-portrait, since it shows a man in his sixties or seventies, certainly not one in his forties.

29

Supposed self-portrait of Leonardo as an older man, in red chalk

Whether an actual self-portrait or not, this drawing served to kill off the image of the painter prevalent in the sixteenth century: that of an athletic, fun-loving, and strikingly attractive man with long eyelashes and a taste for pink tights. It fostered instead a picture of Leonardo as a gray-bearded magus: serious, studious, and scientific. It was a Leonardo made safe for the steam age.

By the beginning of 1496, Leonardo was, typically for him, at work on several other projects besides

The Last Supper

. Some were initiated by Lodovico, while others were the result of Leonardo’s more personal enthusiasms.

Although Leonardo longed for military commissions, Lodovico still regarded him first and foremost as an interior decorator and stage designer. Sometime in 1495, as work at Santa Maria delle Grazie commenced, the duke engaged him to paint the ceilings of several

camerini

, or “little rooms,” in the Castello. The commission was probably mooted more than a year earlier, since the ripped-up letter to Lodovico had urged the duke to “remember the commission to paint the rooms.” These rooms were part of a covered bridge, the Ponticella, recently constructed by Bramante to span the

moat and provide a quiet retreat for Lodovico and Beatrice. Leonardo probably began painting the vaults at the end of 1495, since in November of that year, according to a document, the ceilings had been given their base color and were ready for decoration.

30

At virtually the same time, Leonardo received another commission from Lodovico. He spent the end of 1495 and the first weeks of 1496 preparing the stage set and costumes for yet another theatrical, a five-act comedy by Baldassare Taccone on the theme of Jupiter and Danaë. The play was performed at the end of January in the palace of Lodovico’s cousin Gianfrancesco Sanseverino, one of Galeazzo’s eleven brothers. Leonardo once again engineered spectacular visual and aural effects, making a star rise above the stage “with such sounds,” as Taccone’s stage directions stipulated, “that it seems as if the palace would collapse.” Aerial displays featured prominently, with Mercury flying down from Mount Olympus by means of a rope and pulley. There was also a role for an

annunziatore

, or heavenly messenger, who presumably performed similar aerial acrobatics.

31

Much as he must have enjoyed designing these spectaculars, Leonardo was also working on a project that was undoubtedly of more interest to him. Mercury twirling above the heads of the audience is a reminder of his long-standing interest in flight. He was fascinated by the possibility of humans passing into and through different elements such as water or air. Soon after arriving in Milan he began designing a boat that could travel underwater—in effect, a submarine. It was no doubt inspired by (and even based on) a similar vessel designed by a pupil of Bramante named Cesare Cesariano, who claimed to have made a boat that made subaqueous voyages in the moat beside Milan’s castle and in Lake Como.

32

Most of all, though, Leonardo studied the mechanics of flight. He made close studies of how birds and insects flew, trying to determine how humans might harness technology to take flight themselves. As a young man, he spent much time on riverbanks and beside ditches, watching moths, dragonflies, and bats. Sometime in the early 1480s he drew a dragonfly, writing on the margin of the page: “To see four-winged flight, go around the ditches and you will see the black net-wings.”

33

Another dragonfly appeared in his notebooks a few years later, when he was living in Milan. The sheet of paper included sketches of a bat, a flying fish, and what appears to be a butterfly or moth. He was particularly intrigued by the flying fish. As he pointed out with a note of wonder, the flying fish was able to flit through both water and air.

34

Leonardo soon began putting his observations to practical ends. Inspired by the dragonfly, he designed a bizarre contraption that would have required a pilot rapidly and repeatedly to squat like a human piston while at the same time frantically cranking a windlass connected to four paddle-like wings.

35

Another early design represented an attempt to refine a giant flapping wing. His inspiration this time was the bat, which he believed offered the best model. “Remember that your flying machine must imitate no other than the bat,” he wrote in a note to himself, “because the web is what by its union gives the armor, or strength to the wings.”

36

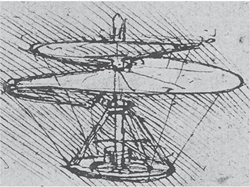

Sometime in the late 1480s, Leonardo drew a diagram for yet another device, a helical contraption that applied to aeronautics the principle of the Archimedean screw. Variations on this rotating helix had been used for over a thousand years to pump water, and Leonardo was familiar with it from his hydraulic projects. Transferring its principles to flight, he imagined a machine that would achieve liftoff by boring its way through the air. His drawing shows a central mast rising from a platform and encircled by spiraling sails, which he stipulated should be made from linen sized with starch. The motive power is unclear, though this rotating spiral could never in his wildest aeronautical dreams have been manned. The sails may have been rotated by the wind, rather like the vanes of a windmill, until the machine rose miraculously skyward. Its rotary motion has often led it to be described (inaccurately) as the prototype for the helicopter.

37

Leonardo’s drawing of a helical contraption

A year or two later, Leonardo drew another diagram of a flying machine. This time he envisioned a pilot strapped prone to a board and operating foot pedals that flapped a pair of overhead wings by means of a system of pulleys. His inspiration for the design of these wings was, as his notes make clear, raptors such as the kite. He even referred to this flying machine as the

uccello

, or bird, and notes and drawings on the reverse of the sheet outlined details of a wing made from cane and starched silk, to which feathers would be glued. He included the observation that the test flight should be conducted over a lake to reduce the risks of a fall, and that the pilot should be equipped with a wineskin to use as an emergency flotation device. However, it is difficult to imagine the furiously pedaling pilot ever achieving liftoff, let alone plunging Icarus-like from the sky.

38

If this

uccello

never reached the flight-testing stage, Leonardo’s next prototype, incredibly, appears to have done so. The flying machine on which he was working as he began his

Last Supper

was a more refined version of the

uccello

. This time he reduced the weight of the device, envisaging his pilot harnessed to a pair of articulated wings activated by foot pedals attached to a system of cables and pulleys. The pedaling motion once again consisted of the pilot rapidly bending and straightening both legs simultaneously.

These wings seem no more promising than the previous prototype, but a page in Leonardo’s notebooks dating from the mid-1490s suggests that he and his “miraculous pilot” were planning a test flight from—terrifyingly—the roof of the Corte dell’Arengo.

39

Leonardo was not the first to have these flights of fancy. He must have known at least some of the stories of various intrepid birdmen who had tried—and inevitably failed—to fly through the air. One of the earliest known attempts at human flight was that by Abbas Ibn Firnas, a physician and poet in Moorish Spain, in 875. Launching himself into the air with a pair of wings made from a silk cape reinforced with willow wands and covered in eagle feathers, he traveled a short distance before crash-landing and breaking his back. His feat was replicated a century and a quarter later in Persia, with even more disastrous results, by a student named al-Jauhari, who was killed after he donned a set of wings and leaped from the roof of a mosque. Around the same time, in England, a Benedictine monk named

Eilmer of Malmesbury, “mistaking fable for truth” (as a chronicler put it), tried to fly like Daedalus. He fastened wings to his hands and feet, then jumped from the top of a church tower. According to the chronicler, he flew for more than two hundred yards before losing control and crashing. He suffered two broken legs “and was lame ever after.”

40