Leonardo and the Last Supper (31 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

Luca Pacioli was born in 1445 in the Tuscan town of Borgo San Sepolcro (today Sansepolcro), forty-five miles southeast of Florence. He was educated by Franciscans before serving an apprenticeship, first with a local merchant and then probably (though no hard evidence exists) with the most famous son of Borgo San Sepolcro, the painter and mathematician Piero della Francesca. Pacioli later described Piero as “the reigning painter of our time,”

11

but the two men shared mathematics rather than painting in common. Piero had written his

Trattato d’abaco

, a book on “the arithmetic necessary to merchants,” at the request of a family of wealthy Borgo merchants. Pacioli, too, became a mathematics teacher to the merchant class, moving to Venice as a young man to teach the three sons of a businessman named Antonio Rompiasi.

After Rompiasi’s death in 1470, Pacioli followed a peripatetic regime, traveling around Italy and giving lessons and lectures on mathematics. In Rome he met the architect Leon Battista Alberti, and in Urbino he became tutor to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, son and heir of the duke. In about 1477 he took his vows as a Franciscan, later returning to Borgo San Sepolcro, where he composed his treatise on mathematics, the

Summa de arithmetica

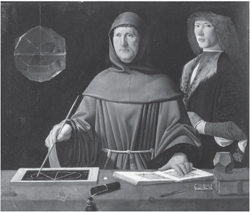

. When he returned to Venice to oversee its publication, an artist named Jacopo de’ Barbari captured him in a portrait. Barbari showed Pacioli’s Franciscan habit cinched at the waist with a cord (the three knots symbolize his vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience) and his head covered with a cowl. His face, however, is clearly visible: that of a middle-aged man with fleshy cheeks and a double chin. To a handsome young man who stands beside him, wearing a haughty glare, he gives a geometry lesson, complete with chalkboard, textbooks, and two models of polyhedra, one of which is made of glass, half-filled with water, and suspended in midair.

Luca Pacioli, by Jacopo de’ Barbari

One of the textbooks shown in the painting is Euclid’s

Elements

. The other is Pacioli’s own

Summa de arithmetica

. As its cumbersome name suggests, this was an encyclopedia, an exhaustive, six-hundred-page-long compendium of arithmetic, algebra, and geometry. As the introduction stated, the book offered “complete instructions in the conduct of business.” It was most famous for its exposition of the system of double-entry bookkeeping used by Venetian merchants—hence Pacioli’s reputation as the Father of Accounting, the Father of the Balance Sheet, and the Father of Profitability.

12

The work’s mind-numbing disquisitions on business accounting may explain the supercilious boredom on the face of the young man by Pacioli’s side. Leonardo, on the other hand, was a great enthusiast for such mathematical treatises. By the 1490s he owned no fewer than six books entitled

Libro d’abaco

—handbooks of mathematical instruction and calculation. He was introduced to mathematics at his abacus school in Vinci, where, according to Vasari, he had baffled his master with questions. Later he became adamant about the importance of the subject. “Let no one read my principles who is not a mathematician,” he famously declared (less famous is the fact that the principles he was referring to were his theories of how the aortic pulmonary valve worked).

13

Ironically, he himself was a poor mathematician, often making simple mistakes. In one of his notes he counted up his growing library: “25 small books, 2 larger books, 16 still larger, 6 bound in vellum, 1 book with green chamois cover.” This reckoning (with its charmingly haphazard system of classification) adds up to fifty, but Leonardo reached a different sum: “Total: 48,” he confidently declared.

14

Pacioli was paid by Lodovico to give public lectures in mathematics. However, the prestige he brought to the Sforza court came not from his expertise in double-entry bookkeeping so much as from his interest in, among other things, polyhedra like the ones shown in the Barbari painting. A polyhedron (from the Greek “many faces”) is a multifaceted geometrical shape such as a tetrahedron (a pyramid), an octahedron (a diamond), or an icosahedron, which is composed of twelve pentagons and twenty hexagons, and looks like a soccer ball. Plato, Euclid, and Archimedes all described the properties of these and other polyhedra, and interest in them revived during

the fifteenth century. The Florentine artist Paolo Uccello used polyhedrons in his paintings (particularly in the form of the padded, doughnut-shaped hat known as a

mazzocchio

) and in a design he created for a mosaic on the floor of the basilica of San Marco in Venice. Pacioli was the latest enthusiast for these kinds of geometrical acrobatics. He claimed to have made glass models of sixty polyhedra while in Urbino (though no record of them has ever been found) and he would make a set in Milan for Galeazzo Sanseverino, to whom he was probably introduced by Leonardo.

Leonardo and Pacioli quickly became friends. Later they would live together in Florence, and Pacioli probably shared space with Leonardo in the Corte dell’Arengo in Milan. Leonardo clearly believed there was much he could learn from the friar, whom he no doubt bombarded with questions. “Learn the multiplication of roots from Maestro Luca,” reads one of his notes.

15

The two men had more in common than merely a love of mathematics. Like Leonardo, who amused courtiers with robotic creatures and tricks such as turning white wine into red, Pacioli appears to have become a kind of highbrow jester at the Sforza court. Soon after arriving in Milan he began work on a treatise called

De viribus quantitatis

(On the Powers of Numbers). It contained not only brain-twisting problems in algebra that Pacioli probably demonstrated and solved before the court, but also numerous magic tricks. Pacioli’s manuscript described such ingenious feats as:

How to Make an Egg Walk over a Table

How to Make an Egg Slide up a Lance by Itself

How to Make a Cooked Chicken Jump on a Table

How to Eat Tallow and Spit Fire

How to Make Worms Appear on Cooked Meat

The secret behind making cooked chicken jump on the table was to mix quicksilver with “a little bit of magnetic powder,” pour the contents into a sealed bottle, and then tuck the bottle inside a chicken “or other cooked thing, which must be hot, and it will jump.” He made worms appear on cooked meat by chopping up the strings of a lute “in great lengths, just like natural worms,” and then concealing them inside the meat. As the meat is roasted, the strings, “made from gut, will slowly twist and they will appear to be worms and those that see them will get sick.”

16

To such entertainments did the “wonder of our times” devote himself. He may have been assisted in some of these recipes by Leonardo, who likewise enjoyed pranks and spectacles. One of Leonardo’s notes gives instructions on how to “make a fire which will set a hall in a blaze without injury.” The trick involves evaporating brandy in a sealed room, suspending powder in its fumes, and then entering the room with a lighted torch. “It is a good trick to play,” he observed. He was also known for inflating sheep intestines with a bellows so they filled the entire room, forcing his guests to crowd into a corner. “He perpetrated hundreds of follies of this kind,” reported Vasari.

17

If Leonardo and Pacioli spent some of their time diverting bored courtiers with these sorts of tricks, they also shared loftier concerns. Soon after Pacioli arrived in Milan, the two men began collaborating on the friar’s magnum opus.

One of Leonardo’s most famous drawings was done a few years before he began work on

The Last Supper

. Carefully sketched in pen and ink, it shows a naked man flapping his arms and legs as if making a snow angel. He is standing inside a square that is intersected by a circle. In his neatest mirror script Leonardo explained the point of the drawing: if you open your legs far enough to reduce your height by one fourteenth and at the same time “spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head,” your navel will be at the center of your outspread limbs and the space between your legs will describe an equilateral triangle.

18

Through this apparently bizarre postural exercise Leonardo evoked the ancient Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius, and consequently his famous drawing is known as

Vitruvian Man

. In

The Ten Books on Architecture

, composed around the time of the birth of Christ, Vitruvius described an experiment in geometry, proportion, and the human body: “For if a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centred at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom.” The body likewise yields a square, Vitruvius claimed, since the distance from the toes to the top of the head equals that from fingertip to fingertip if arms are outstretched.

19

The sole Roman architectural treatise to survive antiquity,

The Ten Books on Architecture

was hugely influential in the fifteenth century. Vitruvius’s treatise

was an eclectic combination of the philosophical and the practical, describing everything from the phases of the moon to how to construct catapults and battering rams. One chapter is entitled “On the Primordial Substance According to the Physicists”; the next is called “Bricks.” Such a book was bound to appeal to Leonardo. “Enquire at the stationers about Vitruvius,” he wrote in one of his ubiquitous book-hunter notes.

20

He must have acquired a copy soon after the first printed edition appeared in 1486.

One chapter of

The Ten Books on Architecture

is called “On Symmetry: In Temples and the Human Body.” Vitruvius seems to have spent a great deal of time measuring people’s faces and bodies. He saw in the human body a combination of ratios and proportions, of fractions and modules, of subtle interrelationships between the different parts. For instance, the distance from the hairline to the tip of the chin was the same, he claimed, as the length of the hand from the base of the palm to the tip of the middle finger. This measure equaled a tenth of a person’s height, while the distance from the chin to the crown was an eighth. “If we take the height of the face itself,” he continued, “the distance from the bottom of the chin to the under side of the nostrils is one third of it; the nose from the under side of the nostrils to a line between the eyebrows is the same.”

21

Because he took nothing on authority, not even on that of Vitruvius, Leonardo began conducting similar experiments of his own. By about 1490 he was systematically measuring the heads, torsos, and limbs of a number of young men, including a pair that he called Trezzo and Caravaggio, after their hometowns in Lombardy. One of these two men was probably the model for

Vitruvian Man

.

22

He was therefore able to come up with an infinite series of refinements and additions to Vitruvius’s measurements, declaring, for example, that the space between the mouth and the base of the nose is one seventh of the face, while the distance from the mouth to the tip of the chin is “a fourth part of the face and equal to the width of the mouth.” Meanwhile the palm of the hand, he discovered, “goes twice into the length of the foot without the toes,” and the distance between the nipples and the top of the head was a quarter of a person’s height.

23