Let’s Get It On! (12 page)

Authors: Big John McCarthy,Bas Rutten Loretta Hunt,Bas Rutten

The idea to form more teams spread like wildfire through police departments across the country, and today the National Public Safety Football League hosts twenty-two teams nationwide.

In 1986, I joined the Centurions and had a blast playing for the next eight years. While some of my teammates had been college and pro ball players, I hadn’t played since my freshman year of high school, so it wasn’t easy. However, by my third year, I made team captain.

We traveled to New York, Phoenix, and Austin to scrap against other teams, and we did it all on our own time and dime to raise money for the Blind Children’s Center of Los Angeles. In 1989, we even had over 40,000 people watching us win our first national championship against the Metro-Miami Magnum Force at the Orange Bowl Stadium in Miami.

Being a part of the Centurions was one of the things that saved me as a police officer. Those were the guys I wanted to be next to.

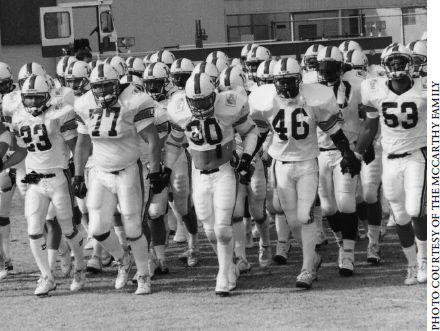

Leading the Centurions out for another game

It wasn’t about individuals; it was about what we could do together. That sense of camaraderie helped fortify me on the tougher days.

Though I didn’t mind West Bureau Narcotics, I’d had my eye on another unit since I’d become an officer. I submitted my application and five months later got the call to transfer to the Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums program, the stupidest unit name I’ve ever heard. It was cool when you heard the acronym CRASH, but when you realized what it stood for, it sounded a bit ridiculous. I didn’t join this antigang unit for the name, though.

CRASH wasn’t a promotion, but it was what the department called a coveted position. It was made up of twenty patrol officers and fifteen detectives who handled gang-related radio calls, and we got to work more than one area at a time. I was still within West Bureau, so I continued to bounce between the Hollywood, Wilshire, West Los Angeles, and Pacific Divisions.

I’d wanted to work in CRASH because I felt it made a difference. We got to deal with the scumbags who intimidated others and set a lot of crimes in motion, so in a way we were getting to the heart of the matter.

I stayed in CRASH for the next four and a half years. It was like navigating through a separate society with its own set of rules, relationships, and vocabulary. My main job was to makes arrests and collect data by talking to the members of the gangs I was assigned to. I had my regulars, but new guys were always popping up into the mix as well. We took down information on everyone, including gang tattoos and secret hand signs, and recorded them onto field identification (FI) cards, which we sorted into each gang’s pile at the end of the day. When a gang-related crime was committed, we could use the cards to find the members who probably were involved or knew something about it.

For a long time, I was assigned to the 18th Street gang, one of the biggest Hispanic gangs throughout Los Angeles and eventually the world. I was also assigned to the Mara Salvatrucha, a ruthless Salvadoran gang. The School Yard Crips was another one I had. There was a turf war on the Venice boardwalk between the Venice Shoreline Crips and the Playboy Gangster Crips out of West Los Angeles in the Cadillac-Guthrie area.

We were in uniform, driving through the gang-infested territories in unmarked vehicles. We could make legal detentions, stopping suspects to talk with them and investigate if we had reason to believe they had done something.

Sometimes I’d stop gang members during what’s called a consensual encounter. I’d pull up in the squad car and ask a gang member to come talk to me. Many of them didn’t know they could just say no and keep walking. I wouldn’t be able to follow them, but I wasn’t about to tell them that. They’d always agree.

Some were no older than ten or eleven and were usually victims of school yard or neighborhood abuses. They’d been harassed enough and thought it was better to join a gang than get the piss beaten out of them until they did.

I understood that these kids were just trying to survive, and sometimes it was hard not to feel bad for them. However, they all had a choice, and they made it. And there were enough kids who said no to it. I knew this was a hard thing to do, but gang life was no joke. One thing TV doesn’t sensationalize about gangs is their finality. There are only two ways of getting out: you die or you move to another county, state, or nation for good.

I arrested one kid when he was twelve years old for being part of a drive-by shooting. He was a member of 18th Street and had been a passenger in the car, so he ended up going to court and being placed in juvenile hall. He was back on the street in about four months.

When he was thirteen, I arrested him again when he was involved in another drive-by shooting. This time he was the shooter. He was sent to the California Youth Authority (CYA), where he stayed until he was sixteen.

He was out for two days before he executed four TMC gang members at a 76 gas station up on Hollywood Boulevard. Not only did he put them down with his first round of shots; he popped an additional bullet in each of their heads with a Calico 9mm, loaded with a 100-round magazine, not your standard choice of weapon for a gang hit.

I’d arrested that kid three times in four years, but he kept committing crimes. I saw this often and couldn’t help but feel frustrated with the system for spitting him back out every time I put him in jail.

Because they chose this life, I never had a problem with gang members shooting other gang members. To me, that was part of natural selection, like animals in the wild. It was survival of the fittest.

The worst part of CRASH was pulling up to see an innocent old man shot on his porch or a little kid dead on a sidewalk after a drive-by shooting. That would get to you and drive you mad. It was all so senseless.

In CRASH, I was considered one of the go-getters and usually brought in high stats. I think I did well because I saw the big picture and knew when to pounce or to hang back and wait. Sometimes keeping a lowlife out of jail would lead to them owing me info on the street, and that could pave the way for the bigger arrests.

I didn’t have a problem giving members and their gangs respect as long as they showed me the same in return. I never downplayed a gang, which sometimes wasn’t easy, especially when they had names like The Magician’s Club or Rebels. If they believed you were decent to them, occasionally they’d give you info because they thought it would screw over a rival gang.

I also liked CRASH because it was the place where I worked with some of the best officers, many who’d go on to really big details, including Bomb Squad and SWAT. It was satisfying to be a part of a team that got results from working hard.

We also played hard, and practical jokes were pretty common. If you were young and new and pulled a practical joke on another officer, they’d call you Morton for being salty, not doing what was expected of a newbie, or they’d call you a boot. Boots had to be careful.

Luckily, I wasn’t a boot any longer and could appreciate a good practical joke. I knew they weren’t meant to ridicule anybody but just to be fun. We dealt with a lot of serious stuff, and laughter helped relieve the stress of it all.

Some of the pranks were quite elaborate. Sometimes we’d put shoe polish on the handle of the squad car’s door or behind the steering wheel, glob Vaseline onto the windshield wipers, run invisible fishing line from the car lights and siren to the door handle, or plug up the air vents with talcum powder. You learned not to be surprised when a beanbag came flying through your patrol car window as you passed another patrol vehicle. Whoever had the beanbag at the end of the day would have to buy everybody else drinks after work. Even sergeants dished out the pranks, and we dished them right back. In CRASH, we were all one.

During my fifty-two months at CRASH, my personality started to emerge on the force, and I also hit a few milestones in my private life.

On November 24, 1989, just eight months after I’d joined the unit, my daughter, Britney, was born. Elaine went into labor on our fifth wedding anniversary, which killed the plans I’d made for a nice dinner in Palmdale, where we’d moved from Covina.

Prior to Britney’s big debut, we were told she was breach but would turn around in time. She didn’t, however, and the doctor decided to perform a Cesarean. Then, just before the procedure, it was discovered that she had suddenly turned into the proper position.

It was a typical Britney move, we’d learn. Like her father, she liked to do things her own way. We’d gone into the hospital at 10:00 a.m., and by the time Britney was born it was 12:13 a.m. She had to have her own day.

Another life change came after a dinner out with friends. A few months after Britney was born, Elaine and I spent an evening with John McKnight and his wife. Both worked for the LAPD. Donna was a public safety radio operator manning the calls coming in from the other officers in a compound four stories under the ground. Elaine mentioned how she wanted to try something new, and Donna suggested she become a radio operator as well.

I knew Elaine was looking for some excitement and this wasn’t the gig for that, but I didn’t say a word till we got home. “Some days,” I said, “you’ll get these high-pressure calls from officers in pursuit, shots will be fired, and you’ll have to stay really calm while you take down the information and call for backup. Other days, you’ll be bored out of your mind, sitting around waiting for calls to come in.

“The difference between that and my job is that at least as a police officer, if I don’t like doing traffic, I don’t have to. I can go do Narcotics or CRASH or SWAT. There are all kinds of jobs within the job. But with the radio operator position, if you don’t like it, there’s nothing else you can go to.”

As the words left my lips, I realized I’d just opened a can of big, fat, ugly worms.

“Okay,” Elaine said. “Then I’ll become a police officer.” She started talking about all the fun positions she could try. She wanted to be a detective and maybe work in child crimes.

I knew there was nothing fun about either of those things, but there was nothing else I could say. Elaine liked being a part of what I did, and I guess my role as a police officer wasn’t going to be any different.

For the next few months, I watched Elaine go through all the testing I’d taken to secure a place at the police academy. She asked me to help her study and prepare. Of course I did, but I kept thinking she’d give up on the idea.

She passed her written tests and then her orals. During the physicals, she had to scale a six-foot wall, and I thought for sure she’d hit her limit here. But she scaled that wall and all the other obstacles placed in front of her. What had taken me a year and a half to accomplish, she got done in three months. She got her letter of assignment to the academy’s class starting in November of 1990.

At the academy, I thought Elaine might buckle with all of the running or self-defense classes. She wasn’t an athlete, and she’d be the first to tell you she wasn’t that coordinated.

I also thought she’d miss our children, Ron and Britney, who were now being taken care of by a nanny at home.

Another thing I thought would change her mind was being yelled at. The training officers got in your face and broke you down, then built you back up the way they wanted. Once again, Elaine proved me wrong and handled it all.

In June of 1991, she graduated and reported to Hollywood for her year’s probation. Although I’d never wanted my wife to become a police officer, I was extremely proud of her accomplishment. It was one of the best things she ever did for herself. It helped her understand a lot about what I did, and it changed her views on the world and people just as it had changed mine.

However, I didn’t want Elaine going out on duty thinking the techniques she’d learned for subduing suspects would work against just anybody, because chances were they wouldn’t. What I knew she had going for her was that she was incredibly bright and would listen. I needed her to understand that her greatest asset as an officer wouldn’t be a choke hold; it would be her mind.

At first she thought I was belittling her. “I could use a choke if I had to,” she said.

“Well, come over here and choke me then,” I said.

She couldn’t.

I hadn’t asked her do it to prove her wrong, but I needed her to know that just because an academy instructor had taught her something and a classmate had tapped when she’d put a choke on him didn’t mean she could do it effectively to anyone.

“Don’t believe the crap they told you about physically controlling people. What you really need is the ability to realize you can’t handle every situation on your own. There’s nothing wrong with asking for help.” Then I taught her to watch the body language of a suspect and told her to get on the radio and call for backup if she saw any warning signs.