Let’s Get It On! (27 page)

Authors: Big John McCarthy,Bas Rutten Loretta Hunt,Bas Rutten

Though the UFC had prevailed in court and been able to put on the show, all Meyrowitz was doing was maintaining status quo. The next state could come after us just as Puerto Rico had.

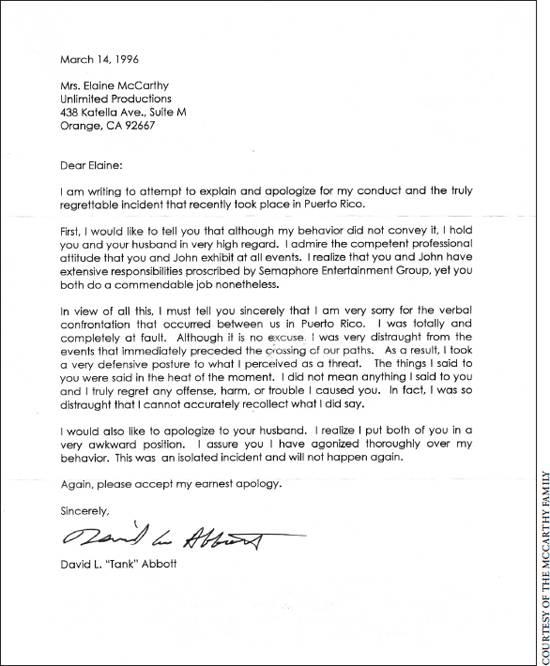

If you believe Tank wrote this letter, I have some great beachfront property for you in Arizona.

That’s exactly what Michigan did. UFC 9 “Motor City Madness,” which was scheduled to take place on May 17, 1996, at the Cobo Arena in Detroit, was a lesson in the pitfalls of shortsightedness.

I’d been flown out to Detroit six weeks before the event for a press conference SEG had hosted to drum up support. Instead, the county’s district attorney dragged us all back into court from that point all the way up till 4:30 p.m. the day of the show.

It was a big story in Detroit, and the press came out in droves to cover it. The battle over No Holds Barred dominated the headlines. At the first hearing, the district attorney’s expert witness on Ultimate Fighting was an old-time boxing writer who’d written a book on . . . guess what. Yes, boxing.

I read the book beforehand and gave SEG’s lawyer a slew of questions to ask the writer to show that he didn’t have any real experience with or knowledge of MMA.

When we reconvened with the courts at the follow-up hearing the week of the show, SEG brought in Emanuel Steward, a renowned boxing trainer who was helping promote this UFC event and spoke on its behalf.

However, the DA went ahead with filing a last-minute injunction, which meant it was another race against time to get the judge to throw it out before the show was advertised to start.

The judge listened to me, Steward, and a couple other prominent local figures willing to defend the promotion.

The judge then decided he saw two similarities between boxing and Ultimate Fighting, and they were closed-fisted punches and headbutts. I don’t know how he derived headbutts from boxing, but that’s what he came up with. He told SEG that if they outlawed closed-handed punches and headbutts, we wouldn’t be categorized as boxing and he didn’t see where the state would have any jurisdiction over what we were doing, because only boxing was in the books. He’d let the show move ahead.

Standing there in court, in front of a throng of media and onlookers, Meyrowitz said, “No problem.”

Outside the courthouse, I grabbed Meyrowitz. “How the fuck are we not going to have any punching in this?”

“I didn’t say there wasn’t going to be any punching,” Meyrowitz coolly answered. “I just said I’d make it illegal. When they punch, you’re going to tell them, ‘That’s illegal.’ And you’re going to have to fine them eventually. When they have to pay that fine, only God knows.”

I was almost sick over Meyrowitz’s decision, but the event was hours away. What could I do? I had to be there to protect the fighters, so I carefully explained the scenario to them all backstage and told them they wouldn’t have to pay any fines accrued that night. Because boxing used closed-fisted punches, open-handed strikes would be interpreted as legal.

I didn’t hear much fuss about it until I got to Ken Shamrock, who was scheduled to rematch Dan Severn in the superfight that night. I gave Ken the same speech I’d delivered to everyone else, but Ken had a totally different reaction.

“John, I can’t do that. My father has a boys’ home, and I can’t set that example for those boys. I’m not going to stand there and knowingly punch illegally just because I know I won’t have to pay the fine.”

“Ken, you do what you gotta do. It’s your choice. If you want to hit him with open hands, hit him with open hands. But I’m telling you, Dan is going to try and hit you with closed hands.”

The result of this whole mess was a subpar event. During the fights, I felt like an idiot instructing the fighters to open their fists when they punched and calling out fouls left and right. And when it got to the Shamrock-Severn fight, it was thirty minutes of a whole lot of nothing, as both circled but barely laid a hand on each other. Severn, who won by split decision, later claimed that the bout was a brilliant strategic display, but I can safely agree with the fans: it was the worst fight in UFC history.

UFC 10 happened six months later on July 12, 1996, at the Fair Park Arena in Birmingham, Alabama. It was christened “The Tournament” because SEG had abandoned the elimination format at UFC 9 for single bouts but brought the tournament style back by popular demand.

UFC 10 introduced Mark Coleman, who’d placed seventh in freestyle wrestling at the 1992 Summer Olympic Games in Barcelona, Spain. Coleman was a standout from the moment he stepped onto the UFC canvas. He had the strength of a monster and could take anyone down, but nobody could do the same to him.

Determined and disciplined by years on the amateur wrestling circuit, Coleman met karate expert Moti Horenstein in a quarterfinal match, took him to the ground, and fed him a heavy serving of punches until I stopped it at two minutes, forty-three seconds.

Horenstein had been a favorite of Meyrowitz’s wife, Ellen, because she thought he was so good-looking. He probably wasn’t so much once Coleman got finished with him.

7

Coleman took out Gary Goodridge in the semis en route to the finals to face Don Frye, the durable wrestler who’d won the UFC 8 tournament back in Puerto Rico. In their quarterfinal bout earlier that evening Frye, who was not a pushover, had pulverized Mark Hall’s body like a side of beef till it was purple, and then in the semifinals he’d beaten an ever-improving Brian Johnston.

Frye-Coleman was one of the first bouts when I could clearly see that the fighters’ skill levels were starting to improve. It was a war. Coleman dominated the bout with his wrestling ability, but Frye, puffy-eyed and staggering at times from exhaustion, was the epitome of toughness.

After nearly twelve minutes of scrapping that culminated with Coleman hammering down punches into Frye’s guard, I intervened. Frye was bleeding, and his right eye was swollen shut. I knew he couldn’t see. Coleman’s family and friends, including his soon-to-be wife, Kelly, flooded the cage and flanked him.

Coleman would have so much success taking his opponents down and punching them into submission, as he had with Frye, that he’d become known as the godfather of ground-and-pound, the term given to his technique. It’s a popular strategy still used today, especially by the wrestlers.

UFC 10 was one of those shows I walked away from and felt it had delivered. It was also the start of a period when wrestling took center stage in the UFC.

That December, SEG hosted its second Ultimate Ultimate event, inviting back the cream of the crop from that year, including its champions and runners-up. We returned to the Fair Park Arena in Birmingham, Alabama, the site of UFC 10.

Tank Abbott fought Cal Worsham in a quarterfinal bout, where Worsham tapped out to his punches on the ground. Worsham became incensed that Abbott had gotten in an extra lick after I’d stepped in to stop it, and I had to physically restrain him against the cage, grabbing the chain link on either side of him. As Worsham pleaded that I disqualify Abbott, I kept telling him to knock it off, giving Worsham the few extra seconds he needed to come back down to Earth. When Worsham’s adrenaline dump subsided, I walked to Abbott, told him what he’d done was bullshit, and raised his hand in victory.

The show’s other highlights included Tank Abbott’s ruthless knockout of Steve Nelmark, who bent backward on the cage like a crash test dummy, and Don Frye’s come-from-behind gut-check victory over Abbott in the finals.

Unfortunately, this night was the second time I felt I was refereeing a fixed bout. In the semifinals, Don Frye and Mark Hall met in a rematch of their UFC 10 bout. In their first encounter Frye had beaten the piss out of Hall, who’d refused to give up. Here, though, Frye ankle-locked Hall to advance to the finals without breaking a sweat.

The fight struck me as odd. Frye, a bread-and-butter wrestler and swing-for-the-fences puncher, had never won a fight by leg lock, and Hall practically fell into the submission. I also knew both fighters were managed by the same guy.

I told Meyrowitz afterward that the fight had been fake, but Meyrowitz asked me how I could think that.

UFC 11“The Proving Ground”

September 20, 1996

Augusta-Richmond County

Civic Center

Augusta, Georgia

Bouts I Reffed:

Mark Coleman vs. Julian Sanchez

Brian Johnston vs. Reza Nasri

David “Tank” Abbott vs. Sam Adkins

Jerry Bohlander vs. Fabio Gurgel

Mark Coleman vs. Brian Johnston

Scott Ferrozzo vs. David “Tank” Abbott

I hit my forearm against Brian Johnston’s nose while leaping in to stop his bout against Reza Nasri, and everyone thought I broke it, but that isn’t true. “John, you hit my nose,” Johnston said, and burst out yelling at the grounded Nasri because they’d exchanged words before the fight. An ill-timed camera cutaway on the pay-per-view made everyone think Johnston was having it out with me.

The main event never happened after Ferrozzo was too gassed from his first fight with Abbott to enter the finals against Coleman. With no alternates left standing, 5,000 fans were treated to Coleman suplexing protégé Kevin Randleman onto his head in an unaired wrestling exhibition. It wasn’t fighting, however, and the hotheaded Randleman cursed the hostile crowd quietly, daring them to get in the cage themselves.

Rumors that Hall had thrown the fight circulated for months, until he came out and openly admitted it. Hall said Frye had offered to pay him, with the mutual manager’s consent, to ensure that Frye made it to the finals as strong as he could be. Hall said he came forward only after Frye didn’t settle up, though Frye denied it ever happened.

I don’t know what kind of deal was struck, and I don’t care what anybody says. I know what I saw.

8

Between Ultimate Ultimate 96 and UFC 12, I finally convinced Meyrowitz and the rest of SEG to add weight divisions. Over the last few shows, I’d told them there were many great 170- to 185-pound fighters who could shine for the promotion, but no matter how talented they were they just wouldn’t be able to overcome the bigger fighters.

I suggested they take a first step by splitting the UFC into two tournament divisions: heavyweight for fighters 200 pounds and over, and lightweight for those under 200. To keep the number of fights down, a preliminary round would decide the two finalists in the four-man tournament, which meant the fighters would compete in two bouts that night instead of three.

SEG decided to give it a try, though the UFC almost didn’t get the chance to test out weight classes.

UFC 12 “Judgment Day” was scheduled to take place on February 7, 1997, in Niagara Falls, New York, but a day before the promotion was forced to move the entire event—fighters, cage, and all—to the Dothan Civic Center in Dothan, Alabama.

The UFC’s New York story had actually begun a few months earlier, when Meyrowitz had hired a lobbyist named James D. Featherstonhaugh shortly after UFC 8 to get mixed martial arts legalized in the state. SEG’s offices were located in New York, and being the center of the universe as well as the haven for boxing for many years, it seemed like a smart progression.