Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (11 page)

Infuriated by the governor's evident hypocrisy, Henry and the others marched out and reconvened in the Apollo Room at Raleigh Tavern. After reconfirming their resolutions, they voted unanimously to enlarge the partial boycott into a total ban on British imports and to send this warning to Parliament: “An attack, made on one of our sister colonies . . . is an attack on all British America. ...”

24

In a final decisionâagain, unanimousâthey ordered a round of drinks . . . and another . . . until they had toasted and emptied their glasses thirteen times.

24

In a final decisionâagain, unanimousâthey ordered a round of drinks . . . and another . . . until they had toasted and emptied their glasses thirteen times.

“To some,” Richard Henry Lee explained to British secretary of state Earl of Shelburne, “the proceedings may appear the overflowings of a seditious and disloyal madness, but your lordship's just and generous attachment to the proper rights and liberties of mankind will discover in them nothing more than a necessary assertion of social privileges founded in reason ... and rendered sacred by a possession of near two hundred years.”

25

25

Chapter 5

To Recover Our Just Rights

As they had after Henry's Stamp Act resolutions, North Carolina, Maryland, New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island joined Virginia in boycotting British imports. Britain felt the effects immediately, and British merchants joined reform-minded political leaders in demanding that Parliament repeal the Townshend Acts. Too many members of Parliament, however, represented single-family “pocket boroughs” and underpopulated “rotten boroughs,” leaving them with no inclination or motives to respond to popular demandsâin either the colonies or England. While the king “plumes himself upon the security of his crown,” warned an anonymous critic in the

Virginia Gazette

, “he should remember that, as it was acquired by one revolution, it may be lost in another.”

1

Virginia Gazette

, “he should remember that, as it was acquired by one revolution, it may be lost in another.”

1

The disruptions in trade with Britain affected every American, including Patrick Henry. Like most farmers, he cleared new fields to grow hemp and flax for making cloth and clothes for himself and his family. Henry installed spinning wheels and a loom and began wearing Virginia cloth made on his own plantation. By the end of 1769, the effects of colony-wide home manufacturing helped cut imports from Britain nearly 40 percent, from about £2.2 million to just over £1.3 million.

Early in 1770, an ugly confrontation between British soldiers and the Sons of Liberty in New York City left both sides with cuts and bruises, but

no fatalities. Boston was the scene of uglier incidents thoughâmany, the result of Boston's unruly street children pelting Redcoats and suspected Redcoat sympathizers with snowballs. When a small mob broke down the door of a Tory shopkeeper, a friend came to his help and fired his musket at the mob, wounding a nineteen-year-old and killing an eleven-year-old. “Young as he was,” the

Boston Gazette

proclaimed, “he died in his country's cause.”

2

no fatalities. Boston was the scene of uglier incidents thoughâmany, the result of Boston's unruly street children pelting Redcoats and suspected Redcoat sympathizers with snowballs. When a small mob broke down the door of a Tory shopkeeper, a friend came to his help and fired his musket at the mob, wounding a nineteen-year-old and killing an eleven-year-old. “Young as he was,” the

Boston Gazette

proclaimed, “he died in his country's cause.”

2

Rabble-rouser Samuel Adams turned the boy's funeral into the largest ever held in Americaâan enormous mass mourning of a martyr that stretched more than a half mile, with more than four hundred, carefully groomed, angelic children leading the coffin and 2,000 mourners walking behind, followed by thirty chariots and chaises.

“Mine eyes have never beheld such a funeral,” John Adams all but sobbed. “This shows there are more lives to spend if wanted in the service of their country. It shows too that the faction is not yet expiringâthat the ardor of people is not to be quelled by the slaughter of one child and wounding of another.”

3

3

Relations between Boston colonists and British troops deteriorated badly. The air filled with a constant staccato of catcalls and cries of “Lobster, Lobster!” at passing British Redcoats. Fights erupted between “lobsters” and waterfront thugs, the latter often goaded (and surreptitiously remunerated) by Samuel Adams. On the evening of March 5, belligerent bands of laborers and soldiers roamed the streets, only narrowly avoiding conflict until nine o'clock that evening, when a young barber's apprentice provoked a sentry at the customs house. The sentry knocked the boy down and sent him off screaming for help. A crowd of boys gathered and pelted the sentry with snowballs, shouting, “Kill him, kill him.” A crowd of men joined in. Suddenly the town's church bells began to peal; townsmen rushed from their homes thinking a fire had broken out; mobs surged through the streets. Hearing of the sentry's predicament, Captain Thomas Preston, the officer of the day, led a squad of six privates and a corporal to the scene, their muskets unloaded but bayonets fixed, with orders to escort the sentry into the customs house, away from the mob's missiles and taunts. By the time they reached the sentry's post, small gangs had swept in from all directions. A mob of waterfront thugs

made it impossible for Preston to march away. Volleys of ice, oyster shells, and stones rained on the troops, with one of the rocks finding its mark. A soldier fell, staggered to his feet, loaded his rifle, and fired into the crowd. A second soldier loaded his weapon and fired a hole into the skull of one of the attackers. Before his body hit the ground a volley of shots left two others dead and eight wounded. Two of the injured later died of their wounds.

made it impossible for Preston to march away. Volleys of ice, oyster shells, and stones rained on the troops, with one of the rocks finding its mark. A soldier fell, staggered to his feet, loaded his rifle, and fired into the crowd. A second soldier loaded his weapon and fired a hole into the skull of one of the attackers. Before his body hit the ground a volley of shots left two others dead and eight wounded. Two of the injured later died of their wounds.

“Endeavors had been systematically pursued for months by certain busy characters to excite quarrels, encounters and combats,” wrote John Adams. “I suspected this was the explosion which had been intentionally wrought up by designing men who knew what they were aiming at better than the instruments employed.”

4

4

Samuel Adams elevated the thugs to near sainthood by staging a grandiose procession with more than 10,000 mourners to carry them to their graves. He encouraged James Bowdoin, a friend from Harvard days, to write (anonymously) an inflammatory pamphlet entitled

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre of Boston

. Although born to mercantile wealth, Bowdoin was a radical who seldom let facts stand in the way of his conclusions. His pamphlet, which called the shootings part of an army conspiracy to silence critics of British rule, was sent to newspapers across the colonies and Britain. Boston silversmith Paul Revere made a grossly inaccurate engraving that showed soldiers, muskets drawn, slaughtering helpless, unarmed townsmen.

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre of Boston

. Although born to mercantile wealth, Bowdoin was a radical who seldom let facts stand in the way of his conclusions. His pamphlet, which called the shootings part of an army conspiracy to silence critics of British rule, was sent to newspapers across the colonies and Britain. Boston silversmith Paul Revere made a grossly inaccurate engraving that showed soldiers, muskets drawn, slaughtering helpless, unarmed townsmen.

As Boston and the rest of the nation waited for the Boston Massacre to expand into a wider conflict, American-born Governor Thomas Hutchinson acted swiftly, promising, “The law shall have its course.” He ordered Preston and the eight soldiers under his command arrested for murder.

5

5

After their arrest, news arrived that a new prime minister, Lord Frederick North, had yielded to merchant pressure and pledged not to levy any new direct taxes on the colonies. At his behest, Parliament repealed all the Townshend Act taxes but the one on tea. The concessions brought an immediate end to American boycotts and a return to normal trade relations for most of the colonies. Renewed prosperity created jobs and weakened popular support for revolution in Boston and other cities. Boston also lost its appetite for vengeance after two Patriot lawyers, John Adams and Josiah

Quincy, agreed to represent the British soldiers at the massacre and presented thirty-six witnesses to testify that civilians had plotted the attack. In addition, they presented the deathbed confession of one of the thugs that the soldiers had not fired until attacked. At the end of Captain Preston's six-day trial, the jury acquitted him, and, in a second trial of the eight soldiers,

the jury acquitted six of them and found two guilty of manslaughter with mitigating circumstances. They were punished in the courtroom by being branded on their thumbs and released.

Quincy, agreed to represent the British soldiers at the massacre and presented thirty-six witnesses to testify that civilians had plotted the attack. In addition, they presented the deathbed confession of one of the thugs that the soldiers had not fired until attacked. At the end of Captain Preston's six-day trial, the jury acquitted him, and, in a second trial of the eight soldiers,

the jury acquitted six of them and found two guilty of manslaughter with mitigating circumstances. They were punished in the courtroom by being branded on their thumbs and released.

Paul Revere's engraving of the Boston Massacre appeared in newspapers across America and inflamed colonist passions against British rule.

(BOSTONIAN SOCIETY)

(BOSTONIAN SOCIETY)

Despite Samuel Adams's polemics and Paul Revere's provocative engraving, the wave of prosperity that followed the repeal of most import duties all but ended tensions between the colonies and their mother country. Indeed, under prodding from leading merchants, colonial assemblies across British America agreed to hold an intercolonial assembly in New York in midsummer to discuss ways to improve major colonial waterways. The House of Burgesses selected Patrick Henry and lawyer Richard Bland as Virginia's delegates. For Henry, it was his first journey out of the colony into populated urban areasâAnnapolis, Philadelphia, and New York. The trip took him through lush Pennsylvania and New Jersey farmlands, where he saw how workers paid by the piece had turned the soil into the most productive fields on earth. For the first time, he saw the reality of English clergyman Jonathan Boucher's pronouncement from the pulpit of Henry's own Hanover County church: “The free labor of a free man who is regularly hired and paid for the work he does and only for what he does, is in the end cheaper than the eye-service of the slave.”

6

6

Henry and his party arrived in New York City on July 10âonly to learn that New York's gruff royal governor John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, had cancelled the conference for fear that delegates might plot against British rule. Henry and the others had little choice but to return home.

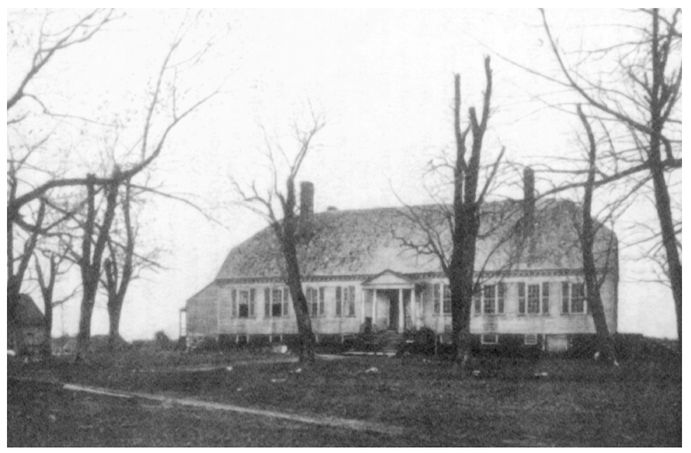

With Henry's increased wealth came a commensurate increase in his family, which now included three boys and three girls, besides his wife, himself, their servants, and slaves. He needed nothing less than a genuine mansion. Throughout his childhood years, Henry had eyed with reverence the estate called Scotchtown. Its previous owner had been John Robinson, the late Speaker of the House of Burgesses, whose malfeasance Henry had exposed. Not far from his Hanover County boyhood home, where his father still lived, Scotchtown was, for the Piedmont at least, a palatial mansion, shaded by stately oaks and elms and landscaped with trimmed box-wood. Approached by a grand staircase of polished stone, Scotchtown measured ninety-four feet long and thirty-six feet deep and boasted sixteen

rooms. Unlike the utilitarian central hall of Virginia's traditional farmhouses, the large central hall at Scotchtown was a reception area that opened into eight other spacious rooms: one of them a grand dining room, another an equally splendid living room. Other roomsâsome with walls paneled with solid mahoganyâincluded a study, music room, card and game room, a small sitting room, and a private dining room for breakfast and informal meals. Eight bedrooms spread across the second floor, while an unfinished attic lay under the roof on the third floor. A hidden staircase built into the rear wall provided an escape in case of assault by Indians or brigands. Two huge chimneys climbed the outer walls at either end of the mansion, while the large kitchen and pantry stood in a nearby outbuilding.

rooms. Unlike the utilitarian central hall of Virginia's traditional farmhouses, the large central hall at Scotchtown was a reception area that opened into eight other spacious rooms: one of them a grand dining room, another an equally splendid living room. Other roomsâsome with walls paneled with solid mahoganyâincluded a study, music room, card and game room, a small sitting room, and a private dining room for breakfast and informal meals. Eight bedrooms spread across the second floor, while an unfinished attic lay under the roof on the third floor. A hidden staircase built into the rear wall provided an escape in case of assault by Indians or brigands. Two huge chimneys climbed the outer walls at either end of the mansion, while the large kitchen and pantry stood in a nearby outbuilding.

Patrick Henry's home at Scotchtown, after its abandonment by its last residents at the beginning of the twentieth century.

(FROM A 1906 PHOTOGRAPH.)

(FROM A 1906 PHOTOGRAPH.)

Twenty miles north of Richmond, Scotchtown was near the main road to Williamsburg and within easy riding distance to both Hanover Courthouse and his father's home at Mount Brilliant. Purchased for a mere £600, Scotchtown boasted 960 acres, where his two boys “were permitted to run quite at large . . . as wild as young colts,” according to Henry's brother-in-law Samuel Meredith.

Other books

Peggy Holloway - Judith McCain 02 - Portrait on Wicker by Peggy Holloway

Little Brats: Hanna: Forbidden Taboo Erotica by Selena Kitt

Manor of Pleasure: An Erotic Historical Romance by Sheridan, Debra

A Taste of Paradise by Connie Mason

Code 13 by Don Brown

Next of Kin by John Boyne

El horror de Dunwich by H.P. Lovecraft

White Collared Part Four: Passion by Shelly Bell

The Ghost Who Wanted Revenge (Haunting Danielle Book 4) by Bobbi Holmes

Call to Treason by Tom Clancy, Steve Pieczenik, Jeff Rovin