Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (14 page)

At Washington's invitation, Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton arrived at Mount Vernon on August 30 to rest up before proceeding together to Philadelphia the following day. Washington's neighbor George Masonâfirmly in favor of a blanket boycott of trade with Britainâjoined them for supper. After a midday dinner the following day, Washington, Henry, and Pendleton mounted their horses and said their farewells to Martha. According to Pendleton, she stood at the door “talking like a Spartan to her son on his going to battle: âI hope you will all stand firm,' she said. âI know George will.'”

6

6

The trio took four days to cover the 150 miles to Philadelphia by horseback and boatâoften riding in the cool, predawn hours before breakfast and stopping for food and rest in Annapolis, Maryland; New Castle, Delaware; and Christina Ferry (now Wilmington), Delaware. Although Philadelphia took little or no notice of most arriving delegates, some 500 dignitaries and a delegation of officers from every military company went out to greet the celebrated Colonel George Washington and escort him and his friends to the city line, where a company of smartly uniformed riflemen and a military band escorted them from the city line past cheering crowds into the center of the city and the elegant City Tavern for a banquet. Of all the delegates, Washington was the most renowned. Every child in Americaâand many in Britainâcould recount his military adventures in the Westâthe blood-curdling ambush by the French and Indians near Fort Duquesne [now Pittsburgh], the slaughter of 1,000 colonial troops, Washington's daring escape through a hail of arrows and bullets, and his courage in leading survivors to safety.

When Washington and Henry arrived in Philadelphia, Richard Henry Lee arranged for them to stay at the palatial mansion of his brother-in-law, Dr. William Shippen Jr., America's foremost lecturer on anatomy. Although

scheduled to convene on Thursday, September 1, Congress did not have a quorum until the following Monday, but a banquet at City Tavern brought many delegates face-to-face before then. It proved a deep disappointment to both Henry and John Adams. “Fifty gentlemen, meeting together, all strangers, are not acquainted with each other's language, ideas, views, designs,” Adams complained to his wife, Abigail. “They are therefore jealous of each otherâfearful, timid, skittish.”

7

Henry was neither fearful nor timid, nor skittish, but he was clearly uncomfortableâout of place, unable to understand the thinking or accents of many delegatesâand with good reason. Without roads or public transport, establishment of cultural ties in

colonial America had been difficult at best and often impossible. Philadelphia lay more than three days' travel from New York, about ten days from Boston, and all but inaccessible overland from far-off towns such as Richmond or Charleston. There were few roads, and foul winter weather and spring rains isolated vast regions of the country for many months and made the Southâand southernersâas foreign to most New Hampshiremen as China and the Chineseâand vice versa. In fact, only 60 percent of Americans had English origins. The rest were Dutch, French, German, Scottish, Scotch-Irish, Irish, even Swedish. Although English remained a common tongue after independence, German prevailed in much of Pennsylvania, Dutch along the Hudson River Valley in New York, French in Vermont and parts of New Hampshire and what would later become Maine. Authorschoolteacher Noah Webster compared the cacophony of languages to ancient Babel, and Benjamin Franklin had complained as early as 1750 that Germantown was engulfing Philadelphia. “Pennsylvania will in a few years become a German colony,” he growled. “Instead of learning our language, we must learn theirs, or live as in a foreign country.”

8

scheduled to convene on Thursday, September 1, Congress did not have a quorum until the following Monday, but a banquet at City Tavern brought many delegates face-to-face before then. It proved a deep disappointment to both Henry and John Adams. “Fifty gentlemen, meeting together, all strangers, are not acquainted with each other's language, ideas, views, designs,” Adams complained to his wife, Abigail. “They are therefore jealous of each otherâfearful, timid, skittish.”

7

Henry was neither fearful nor timid, nor skittish, but he was clearly uncomfortableâout of place, unable to understand the thinking or accents of many delegatesâand with good reason. Without roads or public transport, establishment of cultural ties in

colonial America had been difficult at best and often impossible. Philadelphia lay more than three days' travel from New York, about ten days from Boston, and all but inaccessible overland from far-off towns such as Richmond or Charleston. There were few roads, and foul winter weather and spring rains isolated vast regions of the country for many months and made the Southâand southernersâas foreign to most New Hampshiremen as China and the Chineseâand vice versa. In fact, only 60 percent of Americans had English origins. The rest were Dutch, French, German, Scottish, Scotch-Irish, Irish, even Swedish. Although English remained a common tongue after independence, German prevailed in much of Pennsylvania, Dutch along the Hudson River Valley in New York, French in Vermont and parts of New Hampshire and what would later become Maine. Authorschoolteacher Noah Webster compared the cacophony of languages to ancient Babel, and Benjamin Franklin had complained as early as 1750 that Germantown was engulfing Philadelphia. “Pennsylvania will in a few years become a German colony,” he growled. “Instead of learning our language, we must learn theirs, or live as in a foreign country.”

8

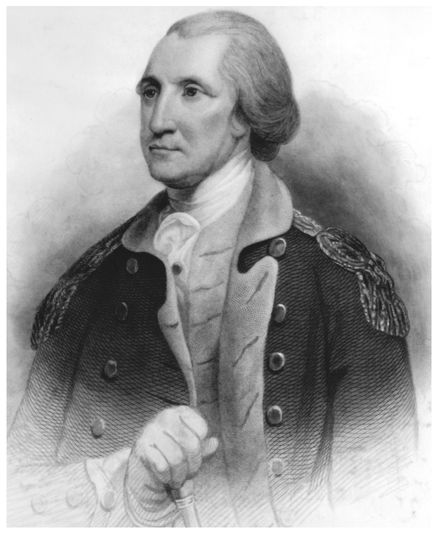

George Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army by the Continental Congress in 1775, but took command too late to prevent the slaughter of American Patriots on Bunker Hill.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

With the Pennsylvania Assembly convening in the State House, the delegates to the intercolonial meeting met in Carpenters' Hall, the craftsmen's union headquarters and meeting hall, about two blocks to the east on Chestnut Street. Only Georgia failed to send a delegate. With Virginia's acquiescence a key to success, the delegates unanimously elected fifty-three-year-old Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, to chair the meeting. Though stout, Randolph idealized Virginia's Tidewater aristocracy, dressed elegantly with a powdered wig and just enough of “Old England” in his bearing to command respect from “commoners.”

Of the procedural questions that delegates faced after Randolph called them to order, they quickly resolved two, dubbing themselves “Congress” (the press would label it the Continental Congress) and giving Randolph the title of “President.” A third question on voting would prove more contentious and, indeed, would hound them and their successors for the next fifteen years: whether to vote as equals, with each colony having one vote, or as representatives of the people, with each delegation casting votes in proportion to the population of its state. The question puzzled the entire

Assembly. None had ever dealt with problems of a free republic. Assigning each colony an equal vote would allow eight or nine colonies with a collective minority of the people to dictate to the majority, while voting proportional to population would allow Virginia and Massachusetts to act in concert and dictate to the eleven other colonies. Delegates sat puzzledâindeed stunned by the grave injustices that each system might produce.

Assembly. None had ever dealt with problems of a free republic. Assigning each colony an equal vote would allow eight or nine colonies with a collective minority of the people to dictate to the majority, while voting proportional to population would allow Virginia and Massachusetts to act in concert and dictate to the eleven other colonies. Delegates sat puzzledâindeed stunned by the grave injustices that each system might produce.

“None seemed willing to break the eventful silence,” said Charles Thomson, who had been elected secretary of Congress, “until a grave looking member, in a plain dark suit of minister's gray, and unpowdered wig arose. All became fixed in attention on him. ...”

9

It was Patrick Henry.

9

It was Patrick Henry.

John Adams described Henry's inaugural address on America's national stage:

Mr. Henry . . . said this was the first General Congress which had ever happened; and that no former congress could be a precedent; that we should have occasion for more general congresses, and therefore that a precedent ought to be established now; that it would be a great injustice if a little colony should have the same weight in the councils of America as a great one. . . .

According to Adams, Henry went on to proclaim,

Government is dissolved. Where are your landmarks, your boundaries of colonies? We are in a state of nature, sir. . . . The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders, are no more. I am not a Virginian, I am an American. I propose that a scale should be laid down; that part of North America which was once Massachusetts Bay and that part which was once Virginia ought to be considered as having a weight. . . . I will submit, however; I am determined to submit, if I am overruled.

10

10

Governor Samuel Ward of tiny Rhode Island objected to Henry's argument, pointing out that each county in Virginia sent two delegates to the House of Burgesses, regardless of any county's population or wealth. To

Henry's surprise, his ally Richard Henry Lee raised another objection to proportionate representation: Congress had no way to measure the population. New York's John Jay stepped in with a compromise: “To the virtue, spirit, and abilities of Virginia we owe much. I should always, therefore, from inclination as well as justice be for giving Virginia its full weight.” Given the impossibility of obtaining a population count, however, Jay said Congress should give each colony an equal voice, but that the voting method not become a precedent until Congress was “able to procure proper materials for ascertaining the importance of each colony.”

11

Henry's surprise, his ally Richard Henry Lee raised another objection to proportionate representation: Congress had no way to measure the population. New York's John Jay stepped in with a compromise: “To the virtue, spirit, and abilities of Virginia we owe much. I should always, therefore, from inclination as well as justice be for giving Virginia its full weight.” Given the impossibility of obtaining a population count, however, Jay said Congress should give each colony an equal voice, but that the voting method not become a precedent until Congress was “able to procure proper materials for ascertaining the importance of each colony.”

11

Congress remained in session seven weeks, during which every delegate had to “show his oratory, his criticism, and his political abilities,” John Adams complained to his wife, Abigail. Calling the proceedings “tedious beyond expression,” he told her that if a motion were made that two plus two equaled five, delegates would debate it endlessly “with logic and rhetoric, law, history, politics and mathematics.”

12

Because of Virginia's importance, at least two Virginia delegates served on every committee, with Henry serving on threeâincluding one with John Adams and Richard Henry Lee to prepare a final address to the king. With so many of his colleagues quoting from it, Henry acquired a translation of

L'Esprit des lois

, or

The Spirit of Laws,

a monumental work by France's Baron de Montesquieu, whom John Adams and other Congress “intellects” cited as casually as a minister citing the Scriptures.

13

12

Because of Virginia's importance, at least two Virginia delegates served on every committee, with Henry serving on threeâincluding one with John Adams and Richard Henry Lee to prepare a final address to the king. With so many of his colleagues quoting from it, Henry acquired a translation of

L'Esprit des lois

, or

The Spirit of Laws,

a monumental work by France's Baron de Montesquieu, whom John Adams and other Congress “intellects” cited as casually as a minister citing the Scriptures.

13

On September 17, Congress endorsed the Suffolk Resolves adopted in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which declared the Coercive Acts unconstitutional and urged the people of Massachusetts to withhold payment of all taxes until Britain repealed the Acts. The Suffolk Resolves (and Congress) urged the people to boycott British goods and form their own armed militia to end the need for British military protection against the Indians. On September 28, Pennsylvania delegate Joseph Galloway proposed a “Plan of a Proposed Union between Great Britain and the Colonies” to create a new American government, with a president-general appointed by the king and a grand council, as an “inferior and distinct branch” of Parliament.

After a New York delegate seconded Galloway, John Jay and South Carolina's Edward Rutledge proffered their support. A curious silence

then gripped Congress, awaiting some opposition. With no one else apparently willing to challenge the proposal, Henry finally stood to denounce it, with what presaged his lifelong opposition to centralized government.

then gripped Congress, awaiting some opposition. With no one else apparently willing to challenge the proposal, Henry finally stood to denounce it, with what presaged his lifelong opposition to centralized government.

The original constitution of the colonies was founded on the broadest and most generous base. The regulation of our trade was compensation enough for all the protection we ever experienced from England. We shall liberate our constituents from a corrupt House of Commons, but throw them into the arms of an American legislature that may be bribed by that nation which avows, in the face of the world, that bribery is a part of her system of government. Before we are obliged to pay taxes as they do, let us be as free as they; let us have our trade with all the world.”

14

14

Led by Henry's and Samuel Adams's fierce opposition, Congress rejected the plan by a single vote, and it later expunged the proposal from the record. “Had it been adopted,” Henry's grandson William Wirt Henry commented later, “the independence of the colonies would have been indefinitely postponed. ...”

15

15

“He is a real half-Quaker,” a spectator at the convention wrote of Henry to Robert Pleasants, Henry's Quaker friend in Virginia. Henry, he said, was “moderate and mild, and in religious matters a saint; but the very devil in politicsâa son of thunder.”

16

16

Except for his denunciation of the Galloway proposal, Henry had no more nor less impact at the Continental Congress than his counterpartsâlargely because he was, for the first time in his life, in the metaphorical big pond of American politics, with some of America's best educated, best trained lawyers. Many had studied in Britain and debated with that nation's most brilliant scholars. To his credit, Henry did not display the meaningless rhetorical tricks and “string of learning” that mesmerized semiliterate mountain people in Hanover County, Virginia. Instead, he held his tongue and had the good sense and political instinct to begin studying Montesquieu's work on government.

On October 14, as Congress prepared its declaration and resolves, Paul Revere galloped to the door of Carpenters' Hall to announce that the Massachusetts

House had met in Salem and declared itself a Provincial Congress. In effect, Massachusetts had staged a coup d'état, overthrowing royal rule and creating the first independent government in America. The Provincial Congress elected John Hancock its president and assumed all powers to govern the province, collect taxes, buy supplies, and raise a militia.

House had met in Salem and declared itself a Provincial Congress. In effect, Massachusetts had staged a coup d'état, overthrowing royal rule and creating the first independent government in America. The Provincial Congress elected John Hancock its president and assumed all powers to govern the province, collect taxes, buy supplies, and raise a militia.

Stunned by the news, members of the Continental Congress did not know whether to cheer the boldness of Massachusetts assemblymen or lament their probable capture and slaughter by British troops. When delegates collected themselves, they issued a declaration supporting “the inhabitants of Massachusetts” and urging “all America . . . to support them in their opposition.”

17

Congress then issued resolutions condemning the Coercive Acts and all the taxes imposed since 1763, along with the practice of dissolving assemblies and maintaining a standing army in colonial towns in peacetime. It issued ten resolutions proclaiming the rights of colonists, including the right to “life, liberty and property” and the right to control internal affairs (including taxes) through their own elected legislatures. Before adjourning, the delegates voted to form a Continental Association to boycott imports from Britain, end exports to Britain and its possessions, and to end the slave trade. The Association agreed to impose an economic boycott on any town, city, county, or colony that violated Association rules. On October 26, Congress prepared a petition for redress of grievances to the king and an address to the British and American peoples. Before adjourning, it resolved to reconvene on May 10, 1775, if Britain did not redress American grievances by then.

17

Congress then issued resolutions condemning the Coercive Acts and all the taxes imposed since 1763, along with the practice of dissolving assemblies and maintaining a standing army in colonial towns in peacetime. It issued ten resolutions proclaiming the rights of colonists, including the right to “life, liberty and property” and the right to control internal affairs (including taxes) through their own elected legislatures. Before adjourning, the delegates voted to form a Continental Association to boycott imports from Britain, end exports to Britain and its possessions, and to end the slave trade. The Association agreed to impose an economic boycott on any town, city, county, or colony that violated Association rules. On October 26, Congress prepared a petition for redress of grievances to the king and an address to the British and American peoples. Before adjourning, it resolved to reconvene on May 10, 1775, if Britain did not redress American grievances by then.

Other books

Scarcity (Special Forces: FJ One Book 1) by Adam Vance

Camp Heat (BBW Western Romance) by South, Jackie

The Trials of Tiffany Trott by Isabel Wolff

Renegade Hearts (The Kinnison Legacy Book 3) by McIntyre, Amanda

The Hostage Bargain by Annika Martin

Las cuatro vidas de Steve Jobs by Daniel Ichbiah

Whispers by Robin Jones Gunn

Under His Care by Kelly Favor

When You Least Expect It by Leiper, Sandra

CROW (Boston Underworld Book 1) by A. Zavarelli