Listening In (20 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

JFK:

I think you’ve had good interesting stuff. I think the Eisenhower was an interesting, sort of, new, different thing.

HARRIS:

Right.

JFK:

Where is Gallup? What’s he doing these days? Does he have a new one coming up?

HARRIS:

Well, I don’t know. He had an awful thing on Negroes the other day, asked whites, “Do you think Negroes in your community really have an equal chance? Or do you think they get a bad break or something?”

JFK:

Yeah.

HARRIS:

I don’t know. I think I’d give him a fifty [unclear] to be perfectly honest, that’s what I’ve heard. We’re picking up quite a number of papers now.

JFK:

Are you?

HARRIS:

Yes, sir. They would syndicate it, we’re going to dry run it, right up to Labor Day. But then the

Detroit Free Press

, the Knight papers picked it up, the [unclear] papers.

Newsday

up here in New York.

JFK:

I should think every city that didn’t have Gallup, that wasn’t a paper that didn’t have Gallup, would love to have you.

HARRIS:

Well, I think we can get that. Now Mr. President, I do have a couple of ideas on ’64 that I think have some merit, one on the whole South thing, and one on this education issue. I’ll be down Tuesday, and I’ll talk to Evelyn about that.

JFK:

OK. OK.

HARRIS:

… if you’d like to see me.

JFK:

I think the problem of the South, of course, those last figures were pretty bad, Gallup had me beat …

HARRIS:

Well, he’s got you so far out in the East, and so low in the South. I’m sure that Eisenhower would be ten points over on the North, I mean the East, and eight points below in the South. So I think …

JFK:

Is that right? You don’t think we’re in that bad shape in the South?

HARRIS:

No, sir, and I can’t believe that 74 percent. That’s running as well as you did in Massachusetts. And I can’t believe it. And my concern there is, he’s going to have you falling ten points in the next three months. Which is bad. I think it’s far more leveled out than that. On the South, I feel very strongly now that I think that, maybe you don’t do it until after the session, but I think the governors are far better than the senators at this point, they’re the guys that really have the political muscle. And I think a great deal can be done there. I have some ideas, should I write something out?

JFK:

OK, fine, I’ll see you next Tuesday.

CALL TO MAYOR RICHARD DALEY, OCTOBER 28, 1963

As the Civil Rights Bill moved forward across the summer and fall of 1963, Kennedy needed to muster all of his allies to advance the cause. When an Illinois Democratic congressman named Roland Libonati defected, there was only one recourse, and that was to call the legendary political boss of Chicago, Mayor Richard Daley. Daley was an old friend who still wielded extraordinary influence and had helped Kennedy carry the crucial state of Illinois in 1960. In this call, Mayor Daley minces no words, telling the President that Libonati will “vote for any goddamned thing you want.” But Daley’s grip was slipping; Libonati did not support the bill. He did, however, pay the expected price, and was not a candidate for renomination in 1964.

JFK:

… with that Judiciary Committee trying to get this Civil Rights together …

DALEY:

Yeah.

JFK:

Roland Libonati

21

is sticking it right up us.

DALEY:

He is?

JFK:

Yeah, because he’s standing with the extreme liberals who are gonna end up with no bill at all. Then when we put together, he’ll, gonna vote for the extreme bill. Then I asked him, If you’ll vote for this package which we got together with the Republicans which gives us about everything we wanted, and he says, “No.”

DALEY:

He’ll vote for it. He’ll vote for any goddamned thing you want.

JFK:

[laughter] Well, can you get him?

DALEY:

I surely can. Where is he? Is he there?

JFK:

Well, he’s in the other room.

DALEY:

Well, you have Kenny, tell Kenny to put him on the wire here.

JFK:

Or would you rather get him when he gets back up to his office? That’s better, otherwise, ’cause he might think …

DALEY:

That’s better. But he’ll do it. The last time I told him, “Now look it, I don’t give a goddamn what it is, you vote for anything the President wants and this is the way it will be, and this is the way we want it, and that’s the way it’s gonna be.”

JFK:

That’d be good.

DALEY:

I’ll get him as soon as he gets back to the …

JFK:

[laughs]

DALEY:

What are they trying to do, they got you hanging under …?

JFK:

Well, we’re gonna, we have a chance to pull this out.

DALEY:

Yeah, but …

JFK:

But you see, of course, these guys, they …

DALEY:

What the hell’s the matter with our own fellows?

JFK:

That’s why, well, it’s good. Krol was … Philadelphia. Billy got him, and if you can get Libonati.

DALEY:

Well, I’ll [catch?] Libonati.

JFK:

OK, good.

DALEY:

Bye now.

JFK:

Thanks, Dick.

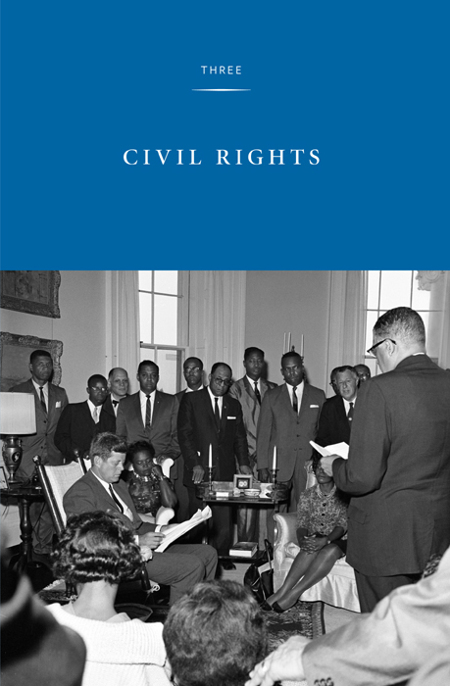

PRESIDENT KENNEDY MEETS WITH NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP) LEADERS IN THE OVAL OFFICE, JULY 12, 1961

Attendees included:

Medgar Evers, Mississippi NAACP field secretary; Calvin Luper, Oklahoma City NAACP Youth Council president; Edward Turner, president of the Detroit NAACP branch; Jack E. Tanner, Northwest Area Conference NAACP president; Rev. W. J. Hodge; Dr. S. Y. Nixson; C. R. Darden, president of the Mississippi NAACP State Conference branches; Kelly M. Alexander, member of NAACP board of directors; Kivie Kaplan, chairman of NAACP Life Membership Committee; and Bishop Stephen G. Spottswood, chairman of the NAACP board of directors.

O

n September 27, 1940, in one of the first Oval Office conversations ever recorded, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Railway Porters stood before Franklin Roosevelt and asked for better treatment for African-Americans. In the two decades that followed, there had been occasional breakthroughs—the integration of the armed forces,

Brown v. the Board of Education

, the integration of Little Rock—but they came too slowly for African-Americans impatient for full citizenship.

The generational shift signaled by Kennedy’s election and the empowerment promised by his speeches only hastened this desire for change, in ways that the Kennedy administration was not at first prepared for. Painfully aware of the thinness of his mandate, JFK liked to quote Thomas Jefferson: “Great innovations should not be forced on slender majorities.” His inaugural address, so eloquent on the subject of freedom around the world, was nearly mute on the great question of how the United States would finally live up to its creed at home.

But there was no stopping history. Kennedy had connected with African-American voters who sensed that they too might enjoy a New Frontier; more than 70 percent of them voted for him, nearly double what Adlai Stevenson had received four years earlier, and their support may well have elected him. On January 21, 1961, the day after Kennedy’s inaugural address, an air force veteran named James Meredith submitted his application to the University of Mississippi (without noting his racial identity). That spring, an interracial Freedom Riders traveled on integrated buses through the South, challenging the segregated bus terminals as an example of systemic racism that oppressed African-Americans.

By the time the Oval Office tapes began to roll in the summer of 1962, the Kennedy administration had come some distance but still had work to do to catch up to where the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement wanted it to be. These tapes record that work in gripping detail, as President Kennedy uses all of the power of his office to persuade reluctant Southern governors to accede to federal power. The forces of resistance were strong; many American newspapers denounced the Kennedy administration, and a significant majority of American voters disapproved of the rapid pace of change. Ever attentive to public opinion, Kennedy knew that he was losing more voters than he was gaining as he began to lead on Civil Rights. But the moment had arrived, in ways that were increasingly obvious. As JFK worked to build a new foreign policy that included Africa and Asia, it was embarrassing to live in a federal city that was still segregated in most ways. The occasional sting of Soviet insults on the subject added to the pressure to bring American reality in line with American rhetoric. Sometimes it seemed that the fates themselves demanded change. One of the most crucial secret messages of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a private note from Kennedy to Khrushchev, was carried away from the Soviet embassy by a young African-American bicycle messenger.

And history argued for movement in other ways. The centennial of the Civil War spoke urgently to those attuned to nuance, as Kennedy surely was. Sometimes that parallel was overt, as when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stood before the Lincoln Memorial and delivered the speech of his life. At other times, it was muted; when Kennedy signed an executive order commanding federal troops to prepare to enforce the integration of the University of Mississippi, he did so on a table that had belonged to Ulysses Grant, a fact he did not reveal to the media.