Listening In (39 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

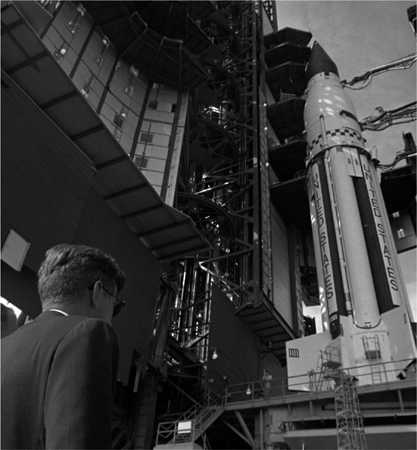

PRESIDENT KENNEDY INSPECTS ROCKET MODELS AT CAPE CANAVERAL, FLORIDA, SEPTEMBER 11, 1962

MEETING WITH JAMES WEBB, SEPTEMBER 18, 1963

This conversation, held a year later, shows considerable evolution from that of November 21, 1962; Kennedy shows more caution and Webb more boldness. Indeed, they have roughly switched roles in a dialogue that was moving very quickly.

JFK:

If I get reelected, I’m not, we’re not, go to the moon in my, in our period, are we?

WEBB:

No, no. We’ll have worked to fly by, though, while you’re president, but it’s going to take longer than that. This is a tough job, a real tough job. But I will tell you what will be accomplished while we’re president, and it will be one of the most important things that’s been done in this nation. A basic need to use technology for total national power. That’s going to come out of the space program more than any single thing.

JFK:

What’s that again?

WEBB:

A basic ability in this nation to use science and very advanced technologies to increase national power, our economy, all the way through.

JFK:

Do you think the lunar, the manned landing on the moon is a good idea?

WEBB:

Yes, sir, I do.

JFK:

Why?

WEBB:

Because …

JFK:

Could you do the same with instruments much cheaper?

WEBB:

No, sir, you can’t do the same.

[break]

WEBB:

While you’re president, this is going to come true in this country. So you’re going to have both science and technology appreciating your leadership in this field. Without a doubt in my mind. And the young, of course, see this much better than in my generation. The high school seniors and the college freshmen are 100 percent for man looking at three times what he’s never looked at before. He’s looking at the material of the earth, the characteristics of gravity and magnetism, and he’s looked at life on Earth. And he understands the universe just looking at those three things. All right, maybe he’s gonna have material from the moon and Mars, he’s going to have already a measurement from Venus about its gravity and its magnetic fields. And if we find some life out beyond Earth, these are going to be finite things in terms of the development of the human intellect. And I predict you are not going to be sorry, no sir, that you did this.

PRESIDENT KENNEDY TOURS THE SATURN ROCKET LAUNCH PAD, CAPE CANAVERAL, FLORIDA, NOVEMBER 16, 1963

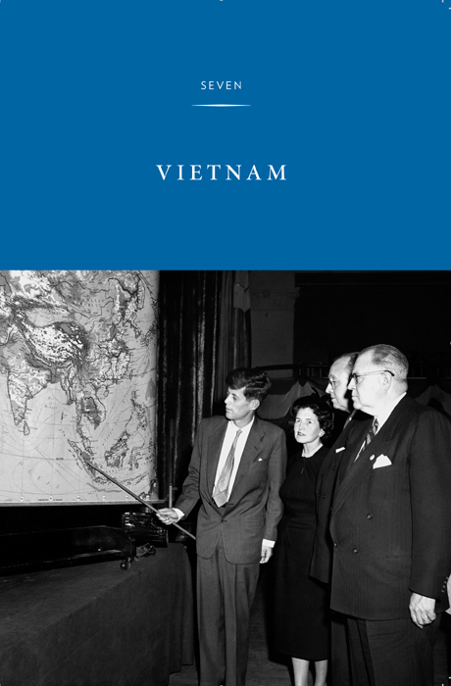

CONGRESSMAN JOHN F. KENNEDY AND ROSE F. KENNEDY DURING A VISIT TO THE BOSTON CHAMBER OF COMMERCE, FOLLOWING A SPEECH ABOUT HIS TOUR OF ASIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST, NOVEMBER 19, 1951

I

n

Profiles in Courage

, Kennedy wrote that politics is a field where “the choice constantly lies between two blunders.” That aphorism must have felt increasingly true to him as he contemplated his bleak options in Southeast Asia. His interest in Vietnam went back surprisingly far; he had traveled there in 1951, as the French were beginning a quite inglorious exit from their former colony. An early dictated reflection indicates Kennedy’s long-standing interest about the underdeveloped world in ways that did not fall into the dualistic framework of the Cold War.

In the early months of the Kennedy administration, Laos was far more in focus than Vietnam, and there the United States was able to engage in minor levels of support for sympathetic allies in a way that did not threaten large-scale conflict. But with Vietnam, a larger and more sophisticated country, it was very difficult to control the outcome of history, as meddling outsiders had discovered before. Under President Eisenhower, the United States had been a very interested observer as Vietnam tried to live under the 1954 Geneva Accords as an independent nation divided into two halves, one of which, South Vietnam, depended on American aid. In the summer of 1963, the options of the United States declined in both number and quality, as the administration of President Ngo Dinh Diem, South Vietnam’s president, began to lose popular approval, brutally repress Buddhists, and threaten new alliances with the French and the North Vietnamese. Even if President Kennedy did not subscribe to the famous “domino theory,” he was deeply troubled by the prospect of “losing” a once-reliable ally in this part of the world. Accordingly, he increased the number of U.S. military advisors in Vietnam. At the end of 1962, there were 11,500; at the end of 1963, more than 16,000.

But as the tapes indicate, Kennedy consistently resisted pressure to send American troops into combat, and privately expressed skepticism toward the military advisors who urged that he do so. As Diem’s fortunes plummeted, Kennedy was unhappy with the increasingly drastic recommendations on the table in late 1963, including a plan to overthrow President Diem and his brother (Ngo Dinh Nhu), hatched by Vietnamese generals with the support of the CIA, the State Department, and his new ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge. That plan ultimately went forward, with the result that Diem and Nhu were brutally executed on November 2, 1963, and a series of unpopular and incompetent governments installed, all of which failed, along with the United States, in the long tragedy of the Vietnam War. Kennedy’s dictated memorandum of November 4 indicates how disturbed he was by that violent result, and the knowledge that the coup had resulted from faulty communications, incomplete instructions, and a process that had spun out of control. Since then, a cottage industry has sprung up speculating on how a second term for Kennedy might have altered the calculus in Vietnam.

DICTATED MEMORANDUM ON CONVERSATION WITH RICHARD NIXON ABOUT VIETNAM, APRIL 1954

On the eve of the French disaster at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, then-Senator Kennedy enjoyed a spirited conversation with the vice president, Richard Nixon, his future adversary in 1960. Given that each would encounter considerable difficulty in Vietnam as president, this early fragment offers a surprisingly early and candid assessment of the problems that would embroil Democratic and Republican administrations in Indochina.

In conversation with Nixon last night, he felt that Reston’s

1

article was, in this morning’s paper about Dulles’

2

failure [unclear] was most unfair, and he added that he remembered when Reston was so wrong about Alger Hiss.

3

And second, he said that Dulles told him that, no, second, he said that the French had asked for air assistance, for an air strike on Dien Bien Phu,

4

that there were a lot of troops concentrated there, that it would have both the advantage of being of military assistance, and also would be a terrific morale factor. That the British, however, refused to join in the strike, and therefore nothing was done about it. The French have been digging us on it since then by saying they asked for help and we rejected them, and Nixon is very bitter against the British, saying they won’t fight except if Hong Kong and Malaya

5

are involved. And they’ve been always trying to play a balance of power, and now, of course, there’s no such balance, no such thing, because it’s really 160 million Americans against 800 million Communists. He admits that the only, I asked him what united action could be taken that would be effective, he admits that there wouldn’t be any use in sending troops in there, as the Chinese would come in, and he finally admitted that the only thing that could be done would be to support the French and the Vietnamese and hope that they were going to be successful. He admits, however, he wonders sometimes [distorted] … they’re really in bad shape over there, and the forces pushing for peace are increasingly strong. [distorted] He said he’s been arguing with Republican colleagues … [distorted] Democrat now he would be attacking the [Eisenhower] administration not for doing too much, and for going too far into Indochina, but for not going [distorted]. He says neither partition nor coalitions, of course, would work. He says there’s enough manpower and materiel, but he said that, of course, that pushing this independence thing is liable to push the French out and there’s no solution there.