Listening In (37 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

MEETING WITH SENATOR HENRY “SCOOP” JACKSON, SEPTEMBER 9, 1963

The Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed with fanfare on August 5, 1963, in Moscow. But President Kennedy still faced a battle at home as he sought Senate confirmation. From August until late September, he reached out to the essential senators. Early in the day on September 9, 1963, he met with the majority and minority leaders, Mike Mansfield (D-Montana) and Everett Dirksen (R-Illinois), both supporters, to discuss the opposition they still confronted. Later the same day, he sat down with Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Washington) for a long conversation that, like so many, took on the world. Jackson, a leading military thinker in the Senate, conveyed with great precision his anxieties about the advantages and disadvantages the treaty would bring. Kennedy countered with eloquent statements of the calming effect that a working treaty would have on a Cold War that had become dangerously hot during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Their extended conversation also touched on Vietnam, where Jackson already had strong reservations, despite his generally hawkish stance. Kennedy confessed the delicacy of his position as a Democratic president trying to launch peaceful initiatives when critics like Richard Nixon and others on the right were attacking most of his positions (“you’ll find there’s a hell of a vested interest in proving any Democratic president to be wrong or soft on Communism”). This long and lucid conversation spoke well for the consultative relationship between the Senate and the presidency, designed by the founding fathers.

JFK:

The other thing is, I don’t think we should apologize to anybody …

JACKSON:

I’m not apologizing to anyone.

JFK:

But it seems to me we do have a story to tell about what we’ve done in the field of defense. The fact is the B-47 would have been out, it might as well have burned under the previous administration, there wouldn’t have been any B-47, we’re the ones who continued, after the Berlin Crisis …

JACKSON:

I agree, that’s why I want to see, if [unclear]. This is what I’m concerned about. I think anyone who is honest with you will tell you that we’ve taken unjustified criticism. Here we’ve had this big buildup, yet the big issue continues to be, I think in this coming campaign, outside of the problem of Civil Rights and so on, the international and national security.

JFK:

We came in here and we had two problems, on January 19, when we had a meeting in there, and Eisenhower and Levinson and everybody recommended that we intervene militarily in Laos. And in the summer, we had a …

JACKSON:

And Berlin was under maximum threat.

JFK:

The fact of the matter is Berlin has never been more secure than it now is, we still kept Laos, we are, if—would improve their public relations, we’re really doing well in that war there, I’ve been reading a report from Hartkinson [?] and Krulak, who have just been out there. So I think we’re good [?] for all the problems in the world, we’re good for the economy, Cuba remains a tough one, but I mean, Christ, we were given that.

JACKSON:

Well, I think the criticism we’re going to be up against is whether we have the will to use our power, and how far we will do it.

JFK:

We made that very clear in two ways. First, in 1961, over Berlin, when we got an ultimatum from Khrushchev, which he had to eat. And the second was last October, in the case of Cuba, when I think we can make the argument, that we’re prepared to, on those occasions … The fact of the matter is that Khrushchev said in June, in Vienna, that by December he was going to sign a peace treaty, and that any American forces that moved across East Germany would be guilty of an act of war. Well, he had to eat it, after we increased our defense budget.

JACKSON:

He can eat an awful lot of crap.

JFK:

I know. They’re going to make that charge, we’ve made that charge against them. But I mean, I think we have an answer.

JACKSON:

But we still might have to intervene in Laos. I went out there for ten days in Vietnam, went on a couple of missions, watched that operation, and if they play at all smart, all they have to do is take Laos, and completely outflank South Vietnam. I think, you have to, from a strategic point of view, hold that area along the Mekong, that’s about two-thirds of Laos …

JFK:

That’s a hell of a place to intervene.

JACKSON:

I know, but if they play it smart, where the hell are we? We just keep pouring a million bucks a day into South Vietnam.

JFK:

I agree, I think that’s why we’ve always felt we would have to indicate to them that we would intervene along the Mekong, we can’t get anybody else to intervene.

JACKSON:

No, I say, it’s a rough one, but I don’t think it’s over with.

JFK:

I think it is.

JACKSON:

The Chinese and Russians.

JFK:

But I’d think twice about Laos, even though we’ve both threatened to, and I think it’s been the reason they haven’t taken all of Laos, because they think we might.

JACKSON:

Well, do it after election.

JFK:

Well, all I want to say, Scoop, was that I think it’d make a hell of a difference in this debate, and I think that having gone this far, having signed this, if we get beaten on it I think we’d find ourselves in a much worse position than we would’ve been if we hadn’t brought it up. Now my guess is, the Chinese Communists may explode a bomb in three years, and we may then decide we do the testing. But at least …

JACKSON:

Sooner than that.

JFK:

Maybe a year, eighteen months. I’m not saying, I’ve never thought this treaty was for good or for long, but I think that as a political effort at this time, we wouldn’t be testing anyway until ’64, and I think that over the next eighteen months it could be of some significance to us.

JACKSON:

Well, again, I think it depends on our will. What we’re really doing is reinstituting the moratorium, we hope with our eyes wide open this time.

JFK:

Except we have underground testing.

JACKSON:

Well, I say, it’s one addition.

JFK:

[unclear]

JACKSON:

Yeah. I think actually they could do more by extrapolation and by various simulated types of tests in addition to actual fairly high-yield underground tests. The great problem, as you know, is the question of what they have found beyond the obvious black capabilities of high-yield nuclear tests. There’s a whole field of new scientific phenomena that no one seems to know the answer, and I’ll be honest with you, if I go along on the treaty, if I do on it, I hope I can, I’m going to try to decide tomorrow, on it, it seems to me we’re going to spend more on delivery systems, because we’re going to have to offset the qualitative advantage that they have in high-yield with more delivery systems, to compensate for the advantage we have quantitatively in weapons, I mean in warheads. And I think it’s going to cost more to test underground, it’s going to run into more money, so this isn’t going to cost less, it’s going to cost more, that’s my own analysis.

JFK:

Yeah, I think there will be some great cost.

JACKSON:

We’re going to have to pay a price for secrecy. That’s a hell of a weapon in their arsenal.

JFK:

We can watch pretty well what they do.

JACKSON:

Well, the only thing, I agree, but the question is, what have they learned, that we really don’t know about.

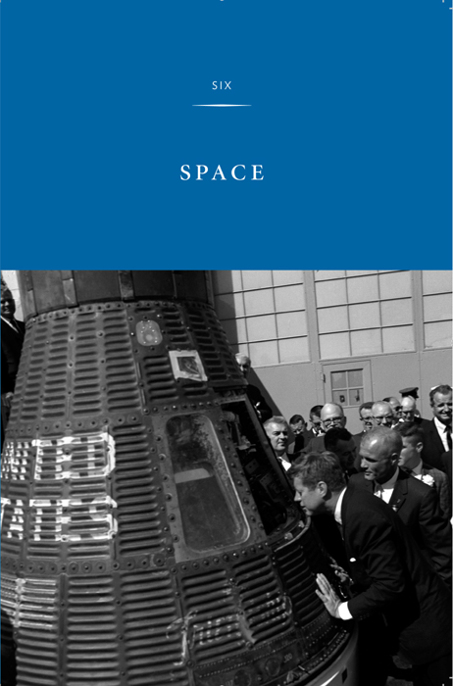

PRESIDENT KENNEDY INSPECTING THE “FRIENDSHIP 7” MERCURY CAPSULE WITH COLONEL JOHN GLENN, CAPE CANAVERAL, FLORIDA, FEBRUARY 23, 1962

T

he Cold War was fought in all of the theaters of the world, including one that was extraterrestrial. Outer space was clearly of the utmost importance to a presidency that embraced the future, technology, and the imperative of responding to all foreign challenges. The first Soviet cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, had flown into space early in the Kennedy administration, on April 12, 1961. That impressive achievement only deepened the resolve of the new administration to forge an achievement of its own in this very new frontier. Accordingly, Kennedy put enormous pressure on government scientists to equal and exceed the Russians. The lead administrator of NASA, James Webb, was an outspoken public servant who often chafed under this pressure, but who also reciprocated Kennedy’s enthusiasm and driving interest. In these two excerpts, President Kennedy and Webb enjoy a spirited exchange about the possibilities opened up by space exploration.

MEETING WITH JAMES WEBB, JEROME WIESNER, AND ROBERT SEAMANS, NOVEMBER 21, 1962

JFK:

Do you put this program … Do you think this program is the top priority program of the agency?

WEBB:

1

No sir, I do not. I think it is one of the top priority programs, but I think it’s very important to recognize here that as you have found what you could do with the rocket, as you found how you could get out beyond the Earth’s atmosphere and into space and make measurements, several scientific disciplines that are very powerful have begun to converge on this area.

JFK:

Jim, I think it is a top priority. I think we ought to have that very clear. You, some of these other programs can slip six months or nine months and nothing particularly is going to happen that’s going to make it. But this is important for political reasons, international political reasons, and for, this is, whether we like it or not, a race. If we get second to the moon, it’s nice, but it’s like being second anytime. So that, if you’re second by six months because you didn’t give it the kind of priority, then, of course, that would be very serious. So I think we have to take the view this is the top priority.