Listening In (42 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

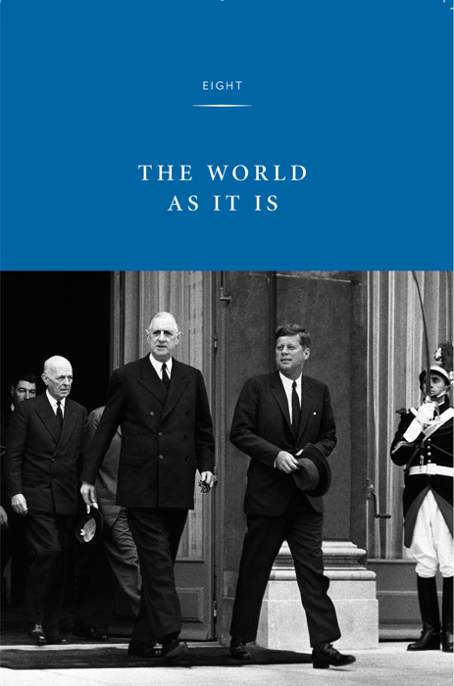

PRESIDENT KENNEDY AND FRENCH PRESIDENT CHARLES DE GAULLE LEAVE THE ELYSÉE PALACE, PARIS, FRANCE, JUNE 2, 1961

“W

e must deal with the world as it is,” President Kennedy asserted in his speech at American University in June 1963.

1

But a world in flux made that a constant challenge. When he ran for president in 1960, one of Kennedy’s many arguments was that the world was changing quickly and the United States was not doing enough to change with it. For eight years, Americans had heard of dominoes falling and chessboards divided into two colors. Kennedy wanted to describe the world with more nuance. As a senator he had nurtured this vision with speeches on Vietnam and Algeria, and as president, he went to considerable lengths to convey his interest in Africa, India, China, Indonesia, the Middle East, North Africa, and many other parts of the global community. There were nineteen new nations in 1960 alone, and as the former colonial powers continued their retreat from dominance, these new nations needed to be addressed with seriousness and respect. Kennedy understood this instinctively; he invited numerous African heads of state to appear at state ceremonies with him and spent surprising time with their ambassadors. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., called him “the Secretary of State for the third world.”

Sometimes this new diplomacy paid surprising dividends—as, for example, when African nations refused to allow Soviet aircraft to refuel on the way to Cuba during the Missile Crisis. At other times, it did not; Vietnam was a former colonial power whose wishes did not run especially parallel to those of the United States, no matter how much money and military aid was offered. But as the new decade dawned, these imperfect aspirations marked an important attempt to give new relevance to the core principles of self-reliance at the heart of American history.

MEETING WITH AFRICA ADVISORS, OCTOBER 31, 1962

Throughout his career as a senator, and then as President, Kennedy displayed an interest in Africa that was unusual for the time, and for anyone schooled, as he surely was, in Cold War brinksmanship. He spoke up for Africa’s relevance to the world, championed African student exchange programs, and referred to Africa 479 times during the 1960 campaign. An impressive number of state visits came from African leaders—eleven in 1961, ten in 1962, and seven in 1963. The Cuban Missile Crisis was barely over when the President’s Africa advisors sat down with him to discuss matters relating to the Congo, where the cruel legacy of Belgian colonialism, combined with more recent acts of violence (particularly the assassination of the charismatic leader Patrice Lumumba, on January 17, 1961), had led to increasing volatility.

G. MENNEN WILLIAMS:

2

Mr. President, there’s one other factor that we ought to have in mind, and that is, we needed the Africa vote in the Cuban situation …

JFK:

Yeah.

WILLIAMS:

… and we needed it in the ChiCom

3

situation. And they’re not going to have much faith in us if we don’t push through with the Congo, so I think we’ve got to keep this thing moving. Now, I think the plan that George has outlined will do it. But I just think we’ve got to show our determination.

JFK:

Well, I think we’ve done a hell of a lot. I mean, I know that we haven’t been successful, but no one can say that we’ve been less than any European country. My God, just look through the list! The English haven’t done anything for us. The French, nothing for us. [unclear] The Germans and Italians can’t even, so that there’s no other Western power that’s doing anything now, we haven’t done enough to get the job done, but …

WILLIAMS:

Now, sir, after Cuba you look ten feet tall to them, and they say, here’s a man who can do it in Cuba, what’s he doing for us here? So I think we can …

JFK:

Well I think we ought to use whatever influence we’ve got very hard now, in the next couple of weeks with these people.

PRESIDENT AND MRS. KENNEDY WELCOME FELIX HOUPHOUET-BOIGNY, PRESIDENT OF THE IVORY COAST, NATIONAL AIRPORT, WASHINGTON, DC, MAY 22, 1962

MEETING ABOUT DEFENSE BUDGET, DECEMBER 5, 1962

JFK often threw out arresting thoughts in his frequent meetings with military advisors, fighting against the conventional doctrine that was so easy to find in Washington. This conversation between Kennedy and his advisors took place shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis and centered on U.S. policy toward Cuba, the military budget, and the value of nuclear weapons, both as a deterrent and as a practical weapon. At the meeting, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara presented the President with a review of the Department of Defense’s $54.4 billion budget for FY 1964. Recommendations on funding, programs, and forces for each of the service branches were also discussed in detail. McNamara was a helpful ally as he brought his formidable executive skills to bear on reforming the enormous bureaucracy he was charged to lead. In this meeting to review the Department of Defense budget, JFK questioned the military’s nimbleness at planning for the years ahead.

4

JFK:

What I’m thinking about is, in Cuba where we’ll be on a unilateral basis, in which we bear total responsibility, Southeast Asia, where you can see a crisis coming, either something in Laos, or something in South Vietnam, number 2 … number 3, where we’d be required to do a rather rushed job in India, in which we’d have to send a lot of equipment, planes. Those seem to me to be the most likely things to happen. What is rather unlikely is to have a long sustained conventional war in Europe, because I don’t think that our allies are preparing for that.

MAXWELL TAYLOR:

We are not prepared to fight that kind of war in Europe at the present time.

JFK:

Well, then what’s the use of having six divisions, plus two spares, plus enough equipment to carry on a conventional war there until we get our [unclear] reduced? I think it makes sense, I’m all for it if it gets the Europeans to do it, but if they’re not going to do it, then that’s what we’ll decide at NATO, then it seems to me that we ought to say to them, this is what we’re prepared to do, but it only makes sense if we’ve got somebody on our right and our left.

ROBERT MCNAMARA:

This is exactly the theme of my statement, I have a draft of it ready now. [some chatter] What I propose to say is exactly this, it makes no sense for us to buy enough for the U.S. divisions, and have our flanks bare at the end of thirty days. And that’s exactly the position we’re in. But I fully agree that in fact, there are other situations in the world that would justify the major part of that, if not all.

JFK:

Well, I’m thinking of … I’ll give you three examples. Number one might be, if civil war in Brazil or someplace, and you’d want to send down a lot of equipment there, your airlift and so on, so I think as long as we don’t sort of concentrate it on Europe, I’m all for it. I just don’t think we ought to be thinking about it, except [unclear] in the rather unlikely contingency, when we’re fighting a conventional war in Europe, until such a point where our [unclear] can sustain us.

CALL FROM SARGENT SHRIVER, APRIL 2, 1963