Listening In (30 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

As president, Kennedy was of course the ultimate arbiter of American foreign and military policy. But if the buck stopped with him, there were still a small number of former presidents he could consult with, who knew the great burdens of the office and had faced decisions nearly as difficult.

JFK:

General, what about if the Soviet Union—Khrushchev—announces tomorrow, which I think he will, that if we attack Cuba that it’s going to be nuclear war? And what’s your judgment as to the chances they’ll fire these things off if we invade Cuba?

EISENHOWER:

Oh, I don’t believe that they will.

JFK:

You don’t think they will?

EISENHOWER:

No.

JFK:

In other words, you would take that risk if the situation seemed desirable?

EISENHOWER:

Well, as a matter of fact, what can you do?

JFK:

Yeah.

EISENHOWER:

If this thing is such a serious thing, here on our flank, that we’re going to be uneasy and we know what thing is happening now, all right, you’ve got to use something.

JFK:

Yeah.

EISENHOWER:

Something may make these people shoot them off. I just don’t believe this will.

JFK:

Yeah, right.

EISENHOWER:

In any event, of course, I’ll say this. I’d want to keep my own people very alert.

JFK:

Yeah. Well, hang on tight!

EISENHOWER:

Yes, sir.

JFK:

Thanks, General.

EISENHOWER:

All right. Thank you.

MEETING WITH SENATORS, OCTOBER 22, 1962

The Constitution ordains that the Senate shall give advice and consent to the President on certain matters of foreign policy, including the making of treaties. Pursuant to that mandate, and as a gesture of respect to his old colleagues, JFK invited several Senate leaders to the White House for a private briefing on October 22, 1962. These senators were intimately involved in all of the legislation that JFK was trying to enact. Richard Russell (D-GA) would be a principal opponent of the Civil Rights Act, which would emerge in 1963 and be enacted in 1964. But on this day, they were all Americans, trying to protect their country.

JFK:

As I say, this information became available Tuesday morning. Mobile bases can be moved very quickly, so we don’t know, [but] we assume we have all the ones that are there now. But the CIA thinks there may be a number of others that are there on the island and have not been set up, which can be set up quite quickly because of the mobility. Intermediate-range ballistic missiles, of course, because of its nature, can take a longer time. We’ll be able to spot those. The others might be set up in the space of a very few days.

Beginning Tuesday morning after we saw these first ones, we ordered intensive surveillance of the island, a number of U-2 flights until Wednesday and Thursday. I talked with, I asked Mr. McCone

13

to go up and brief General Eisenhower on Wednesday.

We decided, the vice president and I, to continue our travels around the country in order not to alert this, until we had gotten all the available information we could. The last information came in on Sunday morning, giving us this last site,

14

which we mentioned.

We are presented with a very, very difficult problem because of Berlin as well as other reasons, but mostly because of Berlin, which is rather … The advantage is, from Khrushchev’s point of view, he takes a great chance, but there are quite some great rewards to it. If we move into Cuba, he sees the difficulty I think we face. If we invade Cuba, we have a chance that these missiles will be fired on us. In addition, Khrushchev will seize Berlin and that Europe will regard Berlin’s loss, which attaches such symbolic importance to Berlin, as having been the fault of the United States, by acting in a precipitous way. After all, they are five or six thousand miles from Cuba, and much closer to the Soviet Union. So these missiles don’t bother them, and maybe they should think they should not bother us.

So that whatever we do in regard to Cuba, it gives him the chance to do the same with regard to Berlin. On the other hand, to not do anything but argue that these missile bases really extend only what we had to live under for a number of years, from submarines which are getting more and more intense, from the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile system, which is in a rapid buildup [and] has a good deal of destruction which it could bring on us, as well as their bombers, that this adds to our hazards but does not create a new military hazard. And that we should keep our eye on the main site, which would be Berlin.

Our feeling, however, is that this would be a mistake. So that, beginning tonight, we’re going to blockade Cuba, carrying out the [action] under the Rio Treaty. We called for a meeting of the Rio Pact countries and hope to get a two-thirds vote from them to give the blockade legality. If we don’t get it, then we’ll have to carry it out illegally or under declaration of war, which is not as advantageous to us.

SENATOR EVERETT DIRKSEN

:

Now, we don’t know if Khrushchev would respond to a complete blockade?

JFK:

A blockade as it will be announced will be for the movement of weapons into Cuba. But we don’t know what the bloc

15

ships will do. In order not to give Khrushchev the justification for imposing a complete blockade on Berlin, we are going to start with a blockade on the shipment of offensive weapons into Cuba that will stop all ships.

Now, we don’t know what the bloc ships will do. We assume that they will probably … We don’t know what they will do, whether they’ll try to send one through, make us fire on it, and use that as a justification on Berlin, or whether he’ll have them all turn back. In any case, we’re going to start on offensive weapons. We will then consider extending it as the days go on to other, petroleum, oil, lubricants, and other matters, except food and medicine. These are matters we will reach a judgment on as the days go on.

Now, in the meanwhile, we are making the military preparations with regard to Cuba so that if the situation deteriorates further, we will have the flexibility. Though the invasion is, the only way to get rid of these weapons is, the only other way to get rid of them is if they’re fired, so that we’re going to have to, it seems to me, watch with great care.

I say if we invade Cuba, there’s a chance that these weapons will be fired at the United States. If we attempt to strike them from the air, then we will try to get them all, because they’re mobile. And we know where the sites are, inasmuch as we can destroy the sites. But they can move them and set them up in another three days someplace else, so that we have not got a very easy situation.

There’s a choice between doing nothing if we felt that would compel Berlin rather than help [unclear] Latin America. So after a good deal of searching, we decided this was the place to start. I don’t know what their response would be. We’ve got two, three, four problems. One will be if we continue to surveil them and they shoot down one of our planes. We then have the problem of taking action against part of Cuba. So I think that—I’m going to ask Secretary McNamara to detail what we’re doing militarily—if there’s any strong disagreement in what at least we set out to do, I want to hear it. Otherwise, I think that what we ought to do is try to keep in very close contact before anything gets done of a major kind differently, and it may have to be done in the next twenty-four hours, because I assume the Soviet response will be very strong and we’ll all meet again. Needless to say, the vice president and I have concluded our campaigning.

SENATOR J. WILLIAM FULBRIGHT:

Mr. President, do I understand that you have decided, and will announce today, the blockade?

JFK:

That’s right. The quarantine.

DEAN RUSK:

Mr. President, may I add one point to what you just said on these matters? We do think this first step provides a brief pause for the people on the other side to have another thought before we get into an utterly crashing crisis, because the prospects ahead of us at this very moment are so very serious. Now if the Soviets have underestimated what the United States is likely to do here, then they’ve got to consider whether they revise their judgment quick and fast. The same thing with respect to the Cubans. Quite apart from the OAS and the UN aspects of it, a brief pause here is very important in order to give the Soviets a chance to pull back from the frontier. I do want to say, Mr. President, I think the prospects here for a rapid development of the situation can be a very grave matter indeed.

SENATOR RICHARD RUSSELL:

Mr. President, I could not space out under these circumstances and live with myself. I think that our responsibilities are quite immense, and stronger steps than that in view of this buildup there, and I must say that in all honesty to myself.

I don’t see how we are going to get any stronger or get in any stronger position to meet this threat. It seems to me that we are at a crossroads. We’re either a first-class power or we’re not. You have warned these people time and again, in the most eloquent speeches I have read since Woodrow Wilson, that’s what would happen if there was an offensive capability created in Cuba. They can’t say they’re not on notice.

The secretary of state says, “Give them time to pause and think.” They’ll use that time to pause and think, to get better prepared. And if we temporize with this situation, I don’t see how we can ever hope to find a place where …

Why, we have a complete justification by law for carrying out the announced foreign policy of the United States that you have announced time … That if there was an offensive capability there, that we would take any steps necessary to see that certain things should stop transit. They can stop transit, for example, though, in the Windward Passage and the Leeward Passage, easily with the nuclear missiles and with these ships. They could blow Guantánamo off the map. And you have told them not to do this thing. They’ve done it. And I think that we should assemble as speedily as possible an adequate force and clean out that situation.

The time is going to come, Mr. President, when we’re going to have to take this step in Berlin and Korea and Washington, DC, and Winder, Georgia, for the nuclear war. I don’t know whether Khrushchev will launch a nuclear war over Cuba or not. I don’t believe he will. But I think that the more that we temporize, the more surely he is to convince himself that we are afraid to make any real movement and to really fight.

JFK:

Perhaps, Mr. Senator, if you could just hear Secretary McNamara’s words, then we could …

RUSSELL:

Pardon me. You just said, if anybody disagrees, and I couldn’t sit here, feeling as I do.

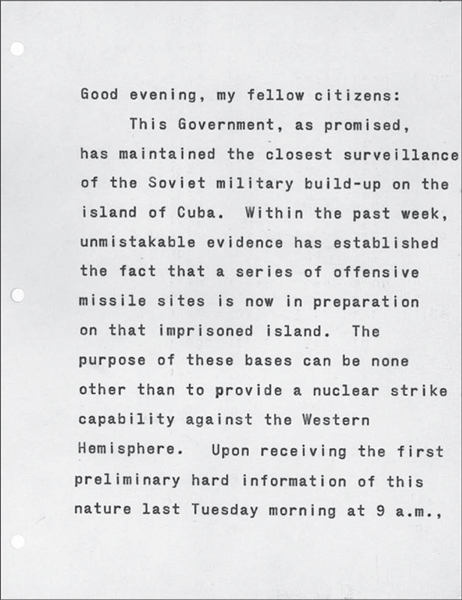

PRESIDENT KENNEDY ADDRESSES THE NATION ON THE SOVIET ARMS BUILD-UP IN CUBA, OCTOBER 22, 1962. MORE THAN 100 MILLION AMERICANS WATCHED THE SPEECH. AS HE SPOKE, THE NATION ELEVATED ITS READINESS FOR WAR AND NEARLY 200 AIRCRAFT CARRYING NUCLEAR WEAPONS WERE AIRBORNE TO AVOID AN ENEMY STRIKE