Living Low Carb (58 page)

Authors: Jonny Bowden

Weight-loss drugs fall into roughly two categories that work by different mechanisms. The first category is appetite suppressants. The second might be called “digestive inhibitors.” All of the following except for Xenical, which is a digestive inhibitor, are appetite suppressants. And again all, except for Meridia and Xenical, are approved for short-term use only. Some innovative physicians are treating obesity and overweight with drugs that are not conventionally used for weight loss but seem to produce it as a side effect. We’ll talk about those later.

Appetite Suppressants

All of the appetite suppressants are called noradrenergic drugs, which means that they do their work by causing the release of two chemicals, norepinephrine and epinephrine. The release of those chemicals causes you to feel less hungry or not hungry at all. Obviously, if you’re not fighting hunger, it’s a lot easier to eat less. The most common side effect of the appetite suppressants is jitters—people sometimes feel wired and have a sense that their heart is beating faster, as if they had drunk a whole pot of coffee. Some people, by the way, like this feeling. They feel they have more “energy.” Some people hate it. The feeling usually goes away in time.

The consumer version of the

Physicians’ Desk Reference

, or

PDR

, says that you should take these drugs only for a “short time,” and when you build up a tolerance for them, you should stop using them. It specifically warns

not

to compensate for the tolerance by upping the dose. Doctors differ in their experience of the “tolerance” aspects. Some feel that in small dosages, patients can stay on these indefinitely and keep getting results. Others cycle the treatment. Dr. Anton Steiner, director of the Tri State Medical Clinic in Los Angeles, has had good results using pharmacology as part of his treatment of obese patients, and will frequently keep patients on these medications for periods of up to nine months. When tolerance to the lower dosages is reached, he will up the dosage periodically until the maximum dose is reached and then put the patient on a “drug holiday.” But he is adamant about using drugs as

part

of an overall program of lifestyle change: he feels extended use gives the patient more time to learn a new lifestyle, get guidance and support for that lifestyle, and build confidence that he or she can maintain it.

Dr. Jay Piatek of the Piatek Institute in Indianapolis is one of the doctors who believe that obese and overweight patients frequently have brainchemistry issues that make it particularly difficult for them to adhere to a change in lifestyle, especially when it comes to their eating behavior. He sees pharmaceuticals as a way of helping his patients modify their brain chemistry so it is easier for them to stay on a diet, resist compulsions to eat, and feel good about themselves while changing their behavior. Piatek has been using the antiseizure drugs topiramate (Topamax) and zonisamide (Zonegran and has had very good results, especially when they’re used in combination with a stimulant such as phentermine. He also uses nutritional supplements and behavior modification as part of an overall program of lifestyle change. His book

The Obesity Conspiracy

discusses his treatment protocol in more detail.

With the exception of Steiner and Piatek, virtually every holistic, integrative, or nutritionally based doctor I spoke to recoiled in horror at the mention of diet drugs. The most frequently cited objections were dependency, adrenal stress and burnout (the drugs are, after all, stimulants), and the fact that you have to keep taking them in order to keep the weight off. Dr. Diana Schwarzbein points out that all stimulants (including coffee) can lead to insulin resistance, which is precisely what you don’t want if you’re trying to lose weight! Stimulants do this by increasing adrenaline, which will eventually results in a “backlash” of insulin production to prevent the breakdown of too many structural and functional proteins in the body.

The drugs my doctor prescribed helped me get to a point where I could really look at my life, reorder my priorities, and change my relationship with food. Now it’s time to think about getting off them.

—Patty MacV.

Considering all those negatives, the gains are pretty unimpressive. When you do the math—which we’ll look at in a moment—you see that the best any of these drugs can do is maybe add 1½ pounds per month to your weight loss efforts, and very few of them can even do that. That’s less than ½ pound a week, and that’s only for the highest dosages in the most successful studies. More typically the results are 1 pound a month, or ¼ pound per week. A big portion of this weight is regained when you stop taking the meds.

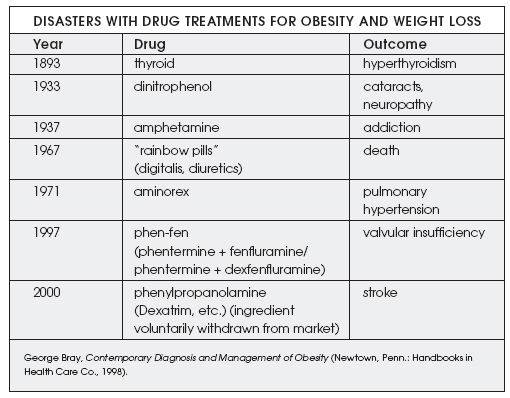

To this I’d like to add that the drug industry doesn’t exactly have a stellar record when it comes to obesity treatments. Take a look at this chart, adapted from Bray’s Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Obesity.

Get my drift?

Following is an examination of the main appetite suppressants on the market.

Phentermine

This is number one on the Hit Parade of appetite suppressants. It’s a schedule 4 drug, which means that the government considers that it has

some

potential for abuse, even though virtually all doctors who prescribe it believe it has none. One of the ingredients in phen-fen, this is the part of the combo that was

not

associated with the valvular problems attached to its partner, fenfluramine. Fenfluramine was pulled off the market, but phentermine remains. It works in an entirely different way from fenfluramine, which increased serotonin release in the brain (serotonin, you may remember, is the “feel-good” neurotransmitter involved in appetite and behavior control). The trade names for phentermine are Adipex-P and Fastin. There’s also a resin-based phentermine called Ionamin. Typically, these three drugs may produce a couple of pounds of additional weight loss

a month

when compared with a placebo, but frequently they produce less. None of them are cheap.

Phendimetrazine

Phendimetrazine is a schedule 3 drug, which means that the government thinks it has higher potential for abuse than a schedule 4 drug. Phendimetrazine has been around since the 1960s, but very few doctors use it any more. Again, the best you’ll get is ½ pound a week more weight loss than with a placebo, and that’s on a good week. There have been reports of problems (ischemic stroke, a fatality) going back to at least 1988. One of its trade names is Bontril. You can find it on the Internet for $89 a month.

Diethylpropion

This schedule 4 drug is sold under the trade name Tenuate. It’s another appetite suppressant that few docs are using these days, but it is hawked on my friendly local Internet pharmacy for $99 per month.

Benzphetamine

A schedule 3 controlled substance, benzphetamine is closely related to amphetamine and has a high potential for abuse. The brand name commonly seen is Didrex. It’s highly addictive and very expensive. One Internet site sells it for $99 a month. Avoid it like the plague.

All of these medications except phentermine are somewhat old-fashioned and are rarely used these days. Phentermine, however, remains very popular.

Phen-Pro refers to the combination of phentermine and Prozac, a combo that some docs experimented with after phen-fen was taken off the market. Phen-Pro isn’t used much anymore, but many doctors

have

noticed that phentermine in combination with a mild antidepressant is a winning combination. The combinations most often cited are phentermine with Lexapro and phentermine with Celexa.

Sibutramine (Meridia)

Sibutramine is one of the two drugs approved by the FDA for long-term use. It was originally studied as an antidepressant but performed very poorly. However, during the studies on depression, it was found to cause a mild amount of weight loss—between 2.2 and 4.4 pounds during the course of the studies.

3

It works by a slightly different mechanism than the appetite suppressants like phentermine. It’s called an SNRI because it is both a

s

erotonin

and

n

orepinephrine

r

euptake

i

nhibitor. The norepinephrine is responsible for the appetite suppression. Sibutramine works directly on the centers in the brain that tell you you’re satisfied. According to Dr. Anton Steiner, you are satisfied sooner when you take sibutramine—one might think of it as a kind of “portion control” pill.

Sibutramine has also been said to “raise metabolism” because it stimulates brown-fat metabolism. Brown fat is a particular kind of metabolically active fat that actually causes the body to burn calories. Everyone got very excited about this thermogenic effect because in lab studies with rodents, there

was

a 30% increase in metabolism; however, with humans, it’s an entirely different story. It

may

stimulate brown-fat metabolism, but only by about 2% to 4% and for less than 24 hours.

4

So how good is sibutramine? The major clinical study that brought this drug onto the radar screen was called the STORM trial—Sibutramine Trial of Obesity Reduction and Maintenance.

5

The researchers—and the marketers of the drug, sold as Meridia—proudly proclaimed that 77% of the people taking it lost a significant amount of weight. Sounds good, right? But let’s look at what really happened.

The initial trial lasted six months, but the overall study continued for two years. Eight European centers recruited 605 obese patients and put them on sibutramine

combined with

a reduced-calorie diet (reduced by 600 calories per day). Of those patients, 467 (77%) lost 5% of their body weight. So far, so good. But what happened afterward? Those 467 patients stayed on the program for another eighteen months. Of these, 115 were taken off the medication and put into a placebo group—they regained weight. The remaining 352 were kept on the meds. Out of that 352, 148 dropped out. Now we’ve got 204 patients left on the meds. Of these 204, 115 were not able to maintain 80% or more of their original weight loss, but 89 people were.

If you look at the number who were left on the meds (352) versus the number who were able to maintain 80% of their weight loss (89), you’re left with—at the end of two years—

a 25% success rate

. Big deal. And that, remember, is just for the people who remained on medication for two years, not for the people who didn’t. Impressive? Not very.

It’s interesting that the people who so solemnly proclaim that this medication was a success due to its first six months are the very same ones who trashed recent studies of the Atkins diet in the

New England Journal of Medicine

6

because, in

one

of the studies, the low-carbers (along with everyone else in the study) regained weight

after

the first six months, just like the people in the sibutramine study did.

And how much weight loss are we talking about here, anyway? In the STORM trial, the original average weight loss was a respectable 24 pounds over the first 6 months (although some people lost much less). That’s about a pound a week—not too shabby. But after the full 2 years, the average weight loss in the sibutramine group—those who remained in the study, that is—was only 12 pounds more than the placebo group, an average of ½ pounds a month. In another 1-year trial, patients treated with sibutramine lost between ½ pound and

8

/

10

pound

per month

more than the placebo group, depending on what dosage they were given, 10 or 15 milligrams.

7

And in other studies,

8

weight loss after one year averaged about 1 pound a month for the folks on 10 milligrams a day, up to a big 1½ pounds a month (or

4

/

10

of a pound a week) for those taking 30 milligrams a day. A review of all studies lasting 36 to 52 weeks found an average weight loss of about ¼ pound a week.

9

Not much of a bargain, considering the price.

On a typical Internet pharmacy site at the time of this writing, a month’s supply of the 10-milligram dose of Meridia was running $189 a month. A month’s supply of the 15-milligram dose would set you back $239. That’s almost $8 a day for

at best

½ pound a week (at worst ½ pound a

month

) more than you could do with a placebo.

Oh, one more thing. Sibutramine was taken off the market in Italy after 50 adverse events and 2 deaths from cardiovascular causes were reported in that country. In the United Kingdom, there were 215 reports of 411 adverse reactions (including 95 serious ones and 2 deaths). Between February 1998 and September 2001, the FDA in the United States received reports of 397 adverse events, including 143 cardiac arrhythmias and 29 deaths (19 of them due to cardiovascular causes). Ten of those deaths involved people under 50 years of age, and 3 involved women under 30.

10