Louis S. Warren (29 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

Cody made efforts to turn his plays into middle-class family entertainment almost from his earliest days on the stage, and there were hints of their potential to become a unifying national art. Buffalo Bill's early appearances alongside the ex-Confederate Texas Jack Omohundro earned praise as a gesture of national reconciliation. In the words of one critic, “here was the âblue and the gray' blended together in one harmonious strain of good fellowship . . . a bright example to the rising generation.”

105

Cody's break with Buntline, after his first season on tour, reflected his impulse to steer clear of the writer's well-earned reputation for class antagonism and anti-immigrant violence. In a long and tumultuous literary and political career, Buntline had scaled impressive heights as rabble-rouser and nativist. He was a founder of the anti-immigrant American Party, commonly called the Know-Nothings, in the early 1850s. Prior to that, in 1849, he was a ringleader of the Astor Place Riot, a melee between thousands of working-class New Yorkers and the state militia outside a production of

Macbeth

which starred an English actor. Buntline and the other leaders of the fracas intended to send a political warning about the dangers of Anglophilia and un-American class hierarchies. But the riot grew so violent that the militia fired repeatedly on the crowd, killing thirty-one people and wounding over a hundred.

106

The Astor Place Riot is the very conflagration which historians credit with driving a wedge between the dramatic tastes of upper-class theatergoers and their lower-class counterparts, thereby dividing the market for theatrical offerings. Buntline's violence, then, helped to create the genus of lower-class entertainment to which Cody was routinely consigned, and from which he fought to escape throughout his stage career. Buntline served a year in prison for his role at Astor Place, but he was hardly finished. In 1852 he fled St. Louis after being indicted for sparking bloody anti-German riots during that year's election. Twenty years later, he was finally arrested for that crime during his sojourn in the city with Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack. This embarrassing moment gave acerbic critics an opening they did not need, but could not forsake: “It is said that Buntline's participation in the little affair here some twenty years ago was merely the advance advertisement of the appearance, this week, with his troupe.”

107

For the first year and a half of her husband's stage career, Louisa Cody sometimes served as troupe seamstress. She accompanied Buffalo Bill on the road, with their three children, Arta, Orra, and Kit.

108

If, as seems likely, the presence of his own middle-class family reinforced Cody's longing to make his entertainment palatable for middle-class family audiences, he was frustrated. He and Buntline tried various methods of luring respectable women to the drama, including the staging of matineesâdaytime performances appealed to family audiencesâand offering free cabinet photographs of Texas Jack, Morlacchi, Ned Buntline, and Buffalo Bill to every “lady” who attended.

109

Endeavoring as he was to fashion his melodramas into family entertainment as early as his first year on the stage, we can only wonder what possessed Cody to invite the broody brawler Wild Bill Hickok to join the troupe in the following year. Hickok's reputation for bloodshed was exaggerated, but Cody knew it was not groundless. Out west, Hickok was a gunfighter and a bona fide killer. He fought often with his fists, many times against the odds, and he usually won. In Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska he had killed several men in gunfights.

110

In contrast with Hickok's frequent dark moods, Cody was unfailingly cheerful and gregarious. He rarely fought with his fists, and when he did, accounts are in disagreement about how the fights ended. When journalists asked Hickok how many white men he had killed, he gave them vastly inflated totals or demurred, muttering words to the effect that “I never killed a man who didn't need killing.” In 1875, a lawyer in Westchester, New York, asked Cody if he had ever shot anyone, by which he meant anyone other than an Indian. Cody grew dark with anger. “No! What do you ask me such a thing for?”

111

Hickok's addition to the company thus was hardly in keeping with Cody's goals for respectable entertainment. There are hints that it did not sit well with the Cody family, either. To be sure, how the Prince of Pistoleers and Mrs. Cody fared as melodramatic troupers sharing the same trains, carriages, hotels, and backstages we shall never know. Shortly after William Cody's death, Louisa Cody dictated her own memoirs, in which she recalled the tour as yet another blissful episode in her long (and in reality, troubled) marriage. As she recalled it, Hickok arrived during a performance, and Cody was out on the stage. Hickok, “stumbling about in the darkness, looked out and gasped as he saw Cody. âFor the sake of Jehosaphat!' he exclaimed, âWhat's that Bill Cody's got on him out there?' ”

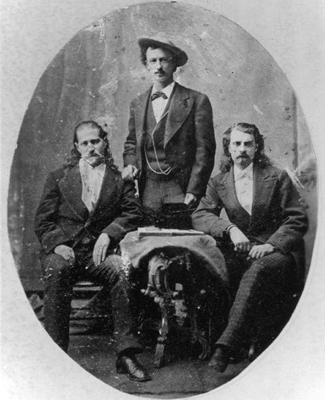

From left to right: Wild Bill Hickok, Texas Jack Omohundro, and

William F. Cody,

1873.

Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Louisa asked if he was referring to Cody's clothes, but “Wild Bill shook his head and waved his arms. âNo,' he was growing more excited every minute, âthat white stuff that's floating all around him.' ”

“Why, Mr. Hickok,” she explained, “that's limelight.”

“Wild Bill turned and grabbed a stage-hand by the arm,” she remembered, “then he dragged a gold piece from his pocket. âBoy,' he commanded, ârun as fast as your legs will carry you and get me five dollars' worth of that stuff. I want it smeared all over me!' ”

The account is fictional (Hickok knew what limelight was, and craved it), but it captures the friction Louisa witnessed that year. Indeed, reading between the lines of William Cody's autobiography suggests the Cody-Hickok stage venture was an uneasy arrangement. Hickok, increasingly jealous of Cody's success, got less compliant as the tour continued. He brawled with billiard room toughs even when Cody implored him to avoid public violence for the sake of the troupeâand presumably, for the sake of the Cody family. He tortured the actors who played Indians in the drama, intentionally firing his pistol blanks so close to their bare legs as to burn them. “Bill's conduct made me angry,” recalled Cody some years later, “and I told him he must either stop shooting the âsupers' or leave the company.”

112

Hickok left. Cody was genuinely sorry to see Wild Bill go, but Hickok's unwillingness to modify his violence for the sake of the combination's image made him a dubious theatrical partner at best. Cody told the tale as if he gave Hickok the chance to stay, and he may have, but evidence suggests that his departure was only part of a wider shake-up in the company. Hickok departed the company at Rochester, on March 11, 1874âthe very day that Louisa and the children separated from the company for a home in that city. Hickok and Louisa, respective embodiments of rough-hewn brawler and middle-class domestic order, likely disembarked at the same platform. One wonders if they were speaking.

113

But for all his labors, Cody's imposture as the ideal Indian fighter was not easily transported to the stage as respectable entertainment, in part because the American public was itself divided on questions of Indian policy, and in part because literary and artistic notions of Indian fighting were not easily made real without creating controversy. In taking Yellow Hair's scalp, Cody situated himself in a liminal position, as the civilized man

driven

to scalping and savage war by the excesses of the Indians who had “massacred” Custer. As the white Indian, he could ostensibly cross the line into savagery and defeat Indians with their own methods, while retaining civilized virtues so as to avoid becoming savage himself. By and large, as we have seen, the maneuver was successful, with the “first scalp for Custer” reaffirming his status as white Indian and theatrical star.

But his descent into Indian modes of combat came with a cost. To Americans, scalping was generally barbaric, a savage gesture beneath civilized society, and beneath professional soldiers, who mostly abhorred the practice. His display of Yellow Hair's scalp and personal belongings at theaters sometimes brought public condemnation, particularly in the strongholds of reformers in New England. The scalp display was banned in Boston, and even in the heated aftermath of Custer's death, his most ardent press supporters, the editors of the

New York Herald,

condemned it as “a disgrace to civilization.”

114

Some fans chided these critics for their sentimentalism, but not all of them were so easily dismissed. Even one Fifth Cavalry trooper, Chris Madsen, a Danish immigrant, was horrified when Cody scalped Yellow Hair, and asked him why he did it. Cody responded that the Cheyenne had a woman's scalp at his waist and an American flag for a loincloth.

115

In other words, the Indian's offenses were so far beyond the pale as to

require

a savage response. The rationale may have let some critics rest easier with Cody's bloody trophy, but the very fact that an explanation was necessary suggests how troubling Buffalo Bill's “real-life” heroism could become for a public continually roiled by arguments over violence and bloodshed in civic life and in war.

By the late 1870s, Cody parried some of his critics' barbs with a gentler drama. Sometimes reviewers even encouraged the “better class” of theatergoers to attend. In

Buffalo Bill at Bay,

a reviewer reported, “The orchestra is excellent. . . . There is no gun firing, except when Bill gives his [shooting] exhibition,” at the middle of the drama, and there was “no slaughtering, so that timid women need feel no aversion to attending.”

116

His Knight of the

Plains

drew a moderate amount of praise, too, both for the improvement in Cody's acting and the absence of gratuitous violence, so that “this new departure is drawing everywhere large audiences of ladies, and the best show-going people.”

117

Wrote another critic, the play was “a vast improvement over all others in which this star has appeared.”

118

By this time, Cody had already outlived his biggest competitors. Wild Bill Hickok had married Agnes Lake, a prominent circus owner, and might have launched an early Wild West show had he not been murdered in 1876. Texas Jack died of pneumonia in Leadville, Colorado, in 1880. Captain Jack was reading his execrable poetry and had all but abandoned the stage. William Cody was seemingly secure as the supreme frontier melodramatist. He was on the verge of respectability.

119

And yet Cody's very success at domesticating his drama threatened to undo him. The fun of Buffalo Bill, after all, had been the interplay between the fake and the real, anchored by his authenticity as the original frontier hero. The death of prominent scouts, and the absence of frontier war to produce any more, removed much of the imitation and took away, too, much of the genre's fun. Just as significant, if Cody's plays were coming to resemble the upmarket version of western melodrama, more like

Across the

Continent

and

Horizon,

then he was simply becoming more like other actors. The energizing element of his presence, his symbol as a common man who made a stage career out of fooling professional actors, would vanish the minute he gained critical acceptance as an actor. In this sense, for all his success on the boards, there was not much chance that he could ever translate it into solid middle-class family entertainment.

The failure to do so would have dire consequences. Cody's career in the 1870s was a straddling act, in which his theatrical appearances and the dime novels about him appealed to the working classes, but his symbolism as an amateur whose theatrical presentation outstrips the professionals resonated with the middle class. Theatrical tastes had once unified American culture, with classical Shakespeare, turgid melodrama, and popular farces playing at the same theatersâindeed, on the same eveningâfor audiences made up of every social class. But since Buntline's incitement to violence outside the Astor Place Theater, class tastes had steadily diverged, with the “better class” of theaters becoming so expensive as to be out of range for middle-class families, and lower-class theaters presenting material that would never be translated into more lucrative middle-class fare.

120

Without more purchase on middle-class loyalties, Buffalo Bill faced a working-class future.

Indeed, as social space, the theater was dubious enough that Cody's reputation as a lowbrow draw would be almost impossible to escape there. The critics who praised Cody's late-1870s performances did so with surprise, contrasting this “new” Cody with the one everybody knewâand

that

Buffalo Bill might have been a symbol to the middle class, but he was clearly a hero to the white working class. Cody usually avoided the bald appeals to nativist bigotry with which Buntline was associated. But there can be little doubt that

Scouts of the Prairie,

with its native-born scouts fending off Indians, Mormons, and immigrantsâsavages allâreinforced the nativism of American laborers, who adored it. Even more, there is plenty of evidence that this segment of his audience saw Buffalo Bill as their hero in the struggle against the privileged classes and foreign immigrants. The 1870s were a decade of economic calamity and labor unrest. The Panic of 1873 and the Great Strike of 1877 set labor and capital at each other's throats, and often pitted laboring American natives against immigrant “scabs.” In the economic downturn that followed 1873, renters in the New York region rose up against the impositions of landlords. The Tenants Mutual Society of Montgomery County, which reportedly “countenanced the burning and destruction of the property of exacting landlords,” included among its members one Charles Montanye, “familiarly called âBuffalo Bill.' ” Montanye was arrested in a civil suit alleging his participation in numerous fires that had scorched the holdings of prominent landowner and rentier George Clark.

121