Louis S. Warren (61 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

There's going to be a Wild West show

Someone asks you to go

White Buffalo Man

Be of courage

Whenever that steamboat whistle toots

Your heart will begin to pound.

12

By moving away from the reservation, Lakotas not only learned of the world; they were able to represent at least some familiar aspects of Sioux culture to the larger world, and to preserve and develop those aspects for themselves. The 1883 ban on Lakota religious ceremonies extended to dances. But, beginning that same year, and continuing for the rest of the Wild West show's life, some of the forbidden dances appeared in the show arena. A banned dance is more imperiled than a forbidden book, because if it is not performed, it will quickly fade from collective memory. Although Wild West Indians did not perform the most sacred dances for crowds, it is not too much to say that social dances like the Omaha Dance and the Grass Dance were preserved partly through the Wild West show.

In fact, down to the present day, Lakota dancers credit Wild West show performers with taking dangerous journeys to protect vital traditions of music and dance that had been driven underground on the reservation. Through Buffalo Bill's Wild West, Indian performers blazed a path out of the Indian agent's domain for their forbidden dances and songs, carrying them into the show arena and ultimately into the performing arts such as Indian dance theater (which remains a popular spectacle in the United States and especially in Europe), and high-stakes Indian dance competitions such as those at the Frontier Days celebrations in Cheyenne, Wyoming. In the twentieth century, Indian powwows became central to song and dance traditions for many Indian peoples. The modern powwow, with its dances, craft exhibitions, and Indian food, open to all, in a sense began with the Wild West show. This legacy helps to explain why the late Calvin Jumping Bull, a descendant of Sitting Bull and Black Elk whose prowess as dancer and singer earned him a place in the Cheyenne Frontier Days Hall of Fame in 2004, credits Buffalo Bill with helping to preserve freedom of expression for Lakota people.

13

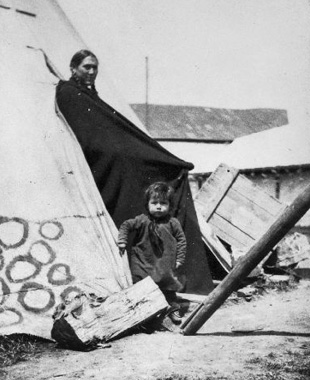

Lakota women and children were central to arena scenes of

village life, and even more important as the center of Lakota

community behind the scenes. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

In addition to its cultural rewards, the most immediate attraction for Lakota joining the Wild West show was money. Even small amounts of cash were a boon to Lakota families struggling in the harsh new world of federal wardship. In 1883, the primary source of subsistence on the Sioux Reserve was rations, payments of food from the government in return for land ceded by the Lakota in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. The treaty stipulated the government could reduce rations when Indians became self-supporting. By the 1880s, agents labeled individual Indians “self-supporting” and slashed their rations, in an effort to force them into wage labor and farming. Famine crept across the reservation.

14

Lakota in Buffalo Bill's Wild West were thus driven to perform in order to keep their kin and themselves from desperation. As attractive as the money was the work itself. On the reservation, employment at digging ditches or grading roads was poorly paid, stultifying, and scarce. Riding a horse and performing dances and mock attacks in Buffalo Bill's Wild West was scarce work, too, but for Indians raised to Plains war, it had the virtues of being familiar and relatively lucrative. On the reservation, a man who secured one of the scarce positions as agency policeman could expect $8 per month, a figure which inched up to $10 by 1890. Other work, such driving a freight wagon, chopping wood, or making butter, was sporadic and paid even less.

15

In contrast, the standard wage for Indians in the Wild West show was $25 per month, with translators and prestigious men designated as “chief” of the show contingent earning monthly salaries of $75 or even $125. With the show's abundant food and the suit of clothes given to all departing Indian men (always useful for formal occasions, and for appearing before authorities back home), show Indianship paid well. Cody committed himself to hiring whole families (to retain the camp's “moral” atmosphere), and in time wives earned $10 per month, with extra cash allowances for children.

16

To secure Indian women's participation, Cody and Salsbury paid them their salaries directly; the usual amount was $10 per month.

17

Some earned more, depending on who their husbands were. Ella Bissonett, who was married to the translator, Bronco Bill Irving, made $25 a month.

18

The presence of children sometimes resulted in an increase in wages by another $5 or $10 per month for child support.

19

Indians committed their funds to farming and livestock raising. But those who did soon discovered that vigilance and continuing contact with home were required to keep property from being stolen, a cause in which they secured the assistance of William Cody. In 1891, writing from Germany, the showman requested that the agent at Pine Ridge investigate the complaints of his Indian contingent, who told him “that the lands formerly occupied by some of them were taken up by other Indians” while the show was out of the country.

20

That same year, Indian women prevailed on Cody to take their part in other disputes over property back home. Relatives at Pine Ridge wrote letters to Calls the Name, a Lakota woman traveling with the show. Letters informed her that the reservation's model farmer, a white man named Davidson, had absconded with a horse and colt belonging to her. Davidson told her family that since Calls the Name was off the reservation, she had sacrificed her property. At the request of Calls the Name, Cody wrote to the agent repeatedly, reminding him that the woman was “absent with consent of the Government” and therefore “entitled to all benefits same as if present.”

21

He wrote also to General Nelson Miles, imploring him to intervene and give Calls the Name “her rights and justice.”

22

Whatever the outcome of these petitions, Indians made Buffalo Billâthe champion of white expansion which had cost Indians almost all their propertyâinto an important ally for Indian entrepreneurs.

Wild West show managers calculated that they paid $74,300 in wages alone to Pine Ridge Indians between 1885 and 1891. Moreover, the amount increased rapidly over time, so that where Sioux employees received $11,500 in the 1886â87 season, by 1889 there were far more Indians in the show, and in total they received $28,800. In the same year, freighting paid an unknown number of Indians at Pine Ridge a total of $9,051. Other jobs paid less. The show was the reservation's most lucrative employer, and one of its biggest.

23

True, other performers received better pay than the Indians did. Cowboys made between $50 and $120 per month. But for Indians, the relative superiority of show wages over other options meant that auditions for Buffalo Bill's Wild West show and similar enterprises drew large, enthusiastic crowds at Pine Ridge.

24

But if Indians seized on the Wild West show as a path into a wage economy, it was, paradoxically, a source of great discontent for American reformers. The entertainment industry was the antithesis of civilized pursuits to Indian agents, who could be as antitheatrical as Puritans where Indians were concerned. In part, this reflected popular sentiment. The nascent industry of traveling outdoor amusements gave rise to a new term, “the show business,” beginning in the 1880s, and like its predecessors, this form of public entertainment was morally dubious.

25

As we have seen, circus entertainers were an itinerant, racially ambiguous crowd in an industry renowned for graft and corruption. More, the mobility of show troupers gave them a suspicious resemblance to nomads. This, compounded with the thievery and confidence games that flowed in the circus's wake, led Americans to label show workers as “gypsies.” The emergence of Indians as show performers thus compounded their essential savagery with a veneer of “gypsy-ness.”

26

Missionary zeal amplified the antitheatricalism of the U.S. Indian Service. To officials, Wild West shows were too much like the theater and the circus to escape their corruptions and deceptions. They brought venereal disease, debauchery, drunkenness, and laziness. Besides, such displays too often emphasized Indian

differences

from whitesâtheir dances, warfare, horsemanship, and other relics of savageryâwhich agents were trying to extinguish. They were exactly the opposite of the assimilation that reservation agents sought.

27

This ideology was a major obstacle to Cody's success and to his Indian employees, too. Working together, often intuitively, the white showman and the show Indians devised strategies to overcome it. They crafted a new rhetoric of Indian presentation, which led Cody to some of his earliest breakthroughs in the domestication of his show for the middle-class public. As we have seen, Cody followed in the tradition of circuses and museums, which touted their “educational value” to reassure an anxious public, and seized on “historical exhibition” and “education” in his advertising, offering a show that was not only amusing, but enlightening.

28

But, just as he promised to educate the audience, he also turned the educational rhetoric inward, onto the show cast. As early as the late 1870s, in order to counter the objections of Indian reformers to having Indians work on the stage, Cody presented his amusements as a vehicle for the education of Indians in the rudiments of civilization. It may have been Indians who gave him the idea. In 1877, a journalist reported that Sword told him how much he enjoyed traveling with Cody's stage combination, learning “the ways of the pale faces for his own good,” and Two Bears announced that he would raise his five children “like white people.”

29

Intuitively, Cody understood that the middle-class public needed to perceive the show as beneficial to Indians before they could let themselves enjoy it. To this end, John Burke and other publicists constantly emphasized the various ways that Buffalo Bill's Wild West show introduced Indians to civilization while protecting them from its blandishments. “Among the changes of [Indian] habit and ideas which have been effected” by Cody's “intelligent and kindly discipline,” wrote one 1885 reviewer, were “the adoption of Christian and civilized attire and even manners, and some progress in the acquisition and use of our language.” At the same time, “it was quite noticeable that they had escaped, as aboriginal visitors rarely do, the corruption of some of the vicious and demoralizing habits of our civilization.”

30

Ideally, Cody's show community was a kind of schoolhouse or home for Indians abroad in civilization, a place in which they learned about the modern world but were also protected from it.

Such images not only reinforced the show's benefits to Indian performers, but enhanced its appeal as a safe place for the entertainment of white families. After all, that which enlightened Indians could not be bad for civilized people. Buffalo Bill's Wild West invited crowds to believe that in being amused, they civilized Indians. This was no small consideration. In the mid-1880s, the average nonfarm worker made about $1.50 per day.

31

Admission to the Wild West show was fifty cents for adults, twenty-five cents for children. A family of four spent a day's wages, $1.50, on admission, 10 cents for a program, more for food and drinks, and for traveling to and from the showgrounds. So, on the way home from the show, a middle-class town dweller could weigh the expense. Was Buffalo Bill's show worth all that money and time? Year after year, they concurred it was, in part because the show entertained them, and in part because of the great ends their entertainment served. Their day with Buffalo Bill helped educate all those Indians. This was a marvelous age, indeed, when a person could strike a blow for progress and civilization merely by being amused.

Successful as this strategy was for Cody, it also meant that any hint of Indian degradation in the show could wreck its middle-class appeal. Thus, Cody's management tended carefully to popular images and official perceptions of Wild West show Indians. When a complaint about Indian drunkenness and immorality in the Wild West show reached federal authorities in 1886, Cody's able publicist, John Burke, reassured authorities such transgressions were impossible: no drinking was allowed by Indians, the only Indian women with the show were married (Burke ignored the issue of interracial sex, as if daring federal authorities to suggest that white women could be so debauched), and the work was too arduous to leave them enough vigor for immorality. To assuage the doubters, Cody and Salsbury promised to pay $100 a month plus expenses “to any philanthropic society agent, any secret service agent, or any person designated by appointment or intimation, to accompany and supervise the personal conduct” of Indians.

32

Such provisions quickly found their way into the show's standard contract with Indian performers.

33