Love and Lament

ALSO BY JOHN MILLIKEN THOMPSON

The Reservoir

Copyright © 2013 John Milliken Thompson

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site:

www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Thompson, John M. (John Milliken), 1959-

Love and lament : a novel / by John Milliken Thompson.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-588-4 1. Young women—Fiction. 2. North Carolina—History—19th century—Fiction. 3. North Carolina—History—20th century—Fiction. 4. Domestic fiction. I. Title.

PS3620.H68325L68 2013

813′.6—dc23

2012030141

Publisher’s Note:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

v3.1

In memory of my grandparents

Mary Myrtle Siler Thompson

and

William Reid Thompson

Contents

Ah my dear angry Lord,

Since thou dost love, yet strike;

Cast down, yet help afford;

Sure I will do the like.

I will complain, yet praise;

I will bewail, approve:

And all my sour-sweet days

I will lament, and love.

—“Bittersweet,” GEORGE HERBERT

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

1893

T

HE DEVIL WAS

coming for her, of that she was sure.

He was riding a big gray horse, and he was all dressed in black, from his slouch hat to his long swallowtail coat to his black-stock tie and pointy hobnail boots. He had a black handlebar mustache, and though she couldn’t see his eyes under his hat brim she knew he was the Devil because the horse’s eyes were red. She was standing by the dusty road clutching her dolly by the arm, her thumb stuck in her mouth. She had come outside to see the thingum, because her mama had told her she should. And now she knew why she’d been afraid to come out. It was because Mama had also told her that someday the Devil was going to get her.

He slowed as he came up, and lifted his hat. And just then came the clang of a horseshoe striking a rock in the road like a bell. She was too scared to do anything but stand there, trying to go invisible, her free hand pressing into her pinafore. His forehead was high and shiny, but there was black hair hanging long in back, and thick

eyebrows that raised. He had a flat smile, if it was a smile at all, and she thought he looked fine, until she remembered who he was.

She shook her head. “I won’t go,” she said.

He brought his horse to a stop and leaned over until he was covering the sun and the trees. “Won’t go where?” he said. He had a deep smooth voice like molasses pouring from the jar.

“I won’t go with you.”

He laughed. “I expect you will someday, and you’ll be glad to.” He put his hat back on and continued up the road. She watched until his black hat disappeared over the rise between the woods and the cornfield, and he never once turned around. She crossed her heart the way Ila had taught her and ran inside, a breeze lifting the hem of her pinafore so that she thought he was still out there trying to snatch her.

“ ’Twasn’t the Devil,” her mother told her. “It was the circuit preacher. Presbyterian, by the sound of him. You’d know if it was the Devil, now go wash your hands and make yourself useful. There’s beans to snap.”

The Devil was a Preacher; the Preacher was the Devil. You had to be good or the Devil would take you away forever and you would never see God. But God could punish you, the same as the Devil, and you had to be especially mindful in church, because God was there, listening and watching. He could help you, but you had to be good, and you couldn’t work on the Sabbath.

Mary Bet would see that Devil Preacher at night sometimes, riding up the road, or standing in a field waiting for her with a flat smile on his face, haunting the edge of her dreams. But she knew he was real. And that someday he would come for her.

SHE WAS BORN

the year the railroad came to Haw County, her arrival associated by her family with that greatest of events yet known in the area, a harbinger, like the railroad itself, of a good and prosperous future.

The more she puzzled over it as a young girl, the clearer it seemed that the railroad brought the misery as surely as the heavens turned in the night sky, as certain as death itself, the hulking black engine an unholy smoking beast on straight and narrow rails of steel. And yet who could deny the excitement the railroad promised, the freedom of movement out beyond the fields and hillocks of the piedmont to the endless blue horizons of the mountains and the seashore?

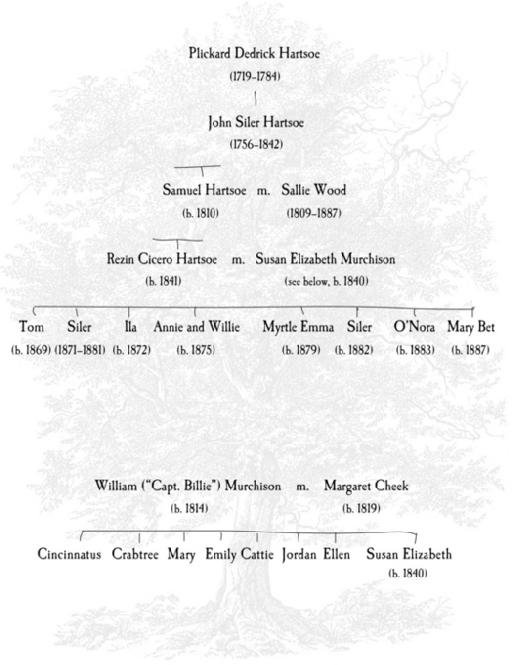

Mary Bet’s grandfathers were men of substance in the decades after the War between the States. Grandfather Samuel, an austere and avaricious grandson of Plickard Dedrick Hartsoe, who’d emigrated from Germany, had but one child, Mary Bet’s father, Rezin Cicero Hartsoe. It was as unusual in those days to have only one child as it was to give property to anyone but that child. Samuel had done well with his mill and wanted his son to know the feeling of making his own way. He’d done well by turning over the milling to younger men, leaving to others the breathing of corn dust and the wrangling of two-thousand-pound stones. The life of a mill owner was much preferred to that of a miller, and Samuel Hartsoe squeezed every penny from his mill that his stern voice and tight-ruled balance sheet allowed.

And then Samuel became an old man and at seventy-one years of age wanted to be remembered for his civic beneficence, and so when there was talk of the railroad coming through Murchison Crossroad, as the town was then known, he offered a slice of the land he owned to the north.