LoveStar (2 page)

Authors: Andri Snaer Magnason

Tags: #novel, #Fiction, #sci-fi, #dystopian, #Andri Snær Magnason, #Seven Stories Press

A CORDLESS MODERN MAN

The cordless modern world had as little as possible to do with cords and cables â not that they were called cords or cables anymore. They were known as chains, and gadgets were known as weights or burdens. People looked at the chains and burdens of the past and thanked their lucky stars. In the old days, people said, we were wire-slaves chained to the office chair, far from birdsong and sunshine. But things had changed. When men in suits talked to themselves out in the street and reeled off figures, no one took them for lunatics: they were probably doing business with some unseen client. The man who sat in rapt concentration on a riverbank might be an engineer designing a bridge. When a sunbathing woman piped up out of the blue that she wanted to buy a two-ton cod quota, bystanders wouldn't automatically assume this was addressed to them, and when a teenager made strange humming noises on the bus, nodding his head to and fro, he was probably listening to an invisible radio. The man who breathed rapidly or got an erection at an inappropriate time and place probably had his visual nerve connected to some hard-core material or was listening to a sex line. (There was no limit to the filth that flooded through the connected minds of some people, but of course it was impossible to ban them from filling their heads with obscenity and violence. You might as well ban thinking.) If someone stood beside you and asked: “What time is it?” and you answered right away: “It's half past nine,” the person would respond, even though there was no one else in sight: “Thanks, but I wasn't talking to you.”

Indridi Haraldsson was a cordless modern man, so the average person could not tell if he was going mad or not. When he spoke to himself in public there might be someone on the other end of the line. When he laughed and laughed it might be for the same reason, or he might be listening to a comedy station, or he could have a funny video playing on the lens. In fact it was impossible to tell what was going on in his head but there was no reason why it should be anything abnormal.

If he ran down the street shouting: “The end of the world is here! The end of the world is here!” most people assumed he was taking part in a radio station competition for a prize of free hamburgers. When he rode naked up and down the shopping center escalator seven times in a row people assumed something similar. It was difficult to tell what prize he was competing for because he was naked and people could only guess his target group from his hairstyle, age, and physical build. Indridi was twenty-one, thin, and pale-skinned, with fair, dishevelled hair, so he was definitely not the target audience of a radio station that advertised bodybuilding, sports cars, highlights, and solariums. He had no tattoos or piercings, so he wasn't the target of the station that played rock and punk and advertised raw beer, unfiltered moonshine, and high tar cigarettes. He was naked and unkempt and definitely didn't belong to any of the more sober target groups. Maybe he was a performance artist. Artists were always busy performing. Perhaps the escalator scene was worth three points on the College of Art's performance art course. Or he could, of course, be in an isolated minority target group. There were plenty of them around, but generally an attempt was made to direct people into a popular area where they could be reached more economically.

If Indridi suddenly barked at someone: “

IIIIICE-COLD COKE

!

IIICCCCCE-COLD COKE

!!!” for ten seconds without his eyes or body seeming to match his words, the reason for this behaviour was simple: the advertisements being transmitted to him were directly connected to his speech center. People assumed he must be an ad howler. He was probably broke enough to fall outside most target groups, so it wasn't worth sending him personal advertisements. But it was possible to send ads through him to others by using his mouth as a loudspeaker. Those who walked past howlers could expect an announcement like:

“

IIIIIICE-COLD COKE

!”

This was more effective than conventional reminders on ad hoardings or the radio. So when Indridi met a man on his way to the parking lot, he howled:

“

FASTEN YOUR SEAT BELT

!

SLOW DOWN

!”

The man had been arrested for speeding without a seat belt. As a punishment he was made to listen to and pay for two thousand edifying reminders from ad howlers. That was probably the best thing about the new technology. It could be used to improve society.

“

LOVE THY NEIGHBOR

!” howled a shady-looking man at half-hourly intervals. A rehabilitated murderer, people would correctly assume, giving him a wide berth. Prisoners could be released early if they howled for charities or religious groups.

Howlers were not all broke. Many were simply scrounging for discounts or perks, and some only became howlers for the first three months of the year while they paid for the latest upgrade of the cordless operating system. Those who didn't get their system upgraded could have problems with their business or communication. Cordless home appliances and auto door-openers only recognized the latest system, and the same applied to the latest car models, so they wouldn't automatically slow down if someone with the old system crossed the road.

If Indridi came across a group of teenagers he might yell:

“

GROOVY SHOES

!

YOU WERE UNBELIEVABLY COOL TO BUY SUCH GROOVY SHOES

!”

Getting someone to buy a product first and then arranging for them to be praised afterward was a revolutionary new strategy. It was believed to strengthen behavior patterns and bring things into fashion earlier.

The announcements were sometimes absurd, sometimes just one word, slogan, or phrase, unconnected to anything else. In that case it was probably part of a longer campaign, a so-called teaser campaign that encouraged people to think long and hard. On the way down the high street you might meet an old woman who said out of the blue: “Smoothness!”

Further down you might meet a teenager who said: “Smartness!”

And even if you veered round sharply and headed up the next street, you would hear whispered from a basement window: “Reliability!”

Finally somebody would come racing down a side street on a bike shouting:

“

FOOOORD

!

FORD

!”

These campaigns always hit their marks; there was no way of escaping them. Everything was measured to within half an inch and the announcement was perfectly tailored to the recipient's target group, which was categorized down to their most minor eccentricity. The howler system was efficient, simple, and convenient, and ordinary citizens could order a howler for a small fee if they needed a reminder.

“You have a meeting with the minister at three o'clock and don't forget your wedding anniversary!”

Those who had recently moved to the city liked to order a howler or two to greet them on the street or strike up a conversation.

“Hello, Gudmund, what lovely warm weather we're having!”

This made the big city seem less cold and unfriendly. Uprooted farmers who wanted to wake up to a rooster call could get their neighbors to crow at 6:00 AM if they were lucky enough to live near a howler.

“Cock-a-doodle-do! Time to wake up!”

Many entrepreneurs felt it essential to receive a confidence boost first thing in the morning:

“You're the best!” said the Chinese cleaning woman.

“No one can stop you, Magnus!” said the shifty caretaker.

“You're looking good!” said the taxi driver. “Today's a day to win!”

Passersby were prepared for anything, so no one paid any attention when Indridi sat in a café and wept. He cried his eyes out in a corner, but few people thought to ask him what was wrong. It was probably Greek tragedy week with his target group. Or he could be an advertising trap.

“Why are you crying?”

“I want a Honda so much, they're such great cars, and there's an amazing offer this week.”

Advertising traps or AdTraps went further than howlers; they hired out not only people's speech centers but also their primitive biological and emotional reflexes. The method was still technologically imperfect so sometimes traps couldn't stop laughing or crying for days on end.

Many people let themselves be persuaded to become traps, as it paid as much as ten conventional speech-center ads and was generally more effective, especially if people were made to do something funny like wet themselves, cry in public, or say to a woman with a howling baby:

“Now would have been a good time to have 100 percent absorbent Pampers!”

When the cordless, connected modern man emerged on the scene with his lens and invisible earpieces, most borders were broken down. For example, it was never possible to know where a company's parameters really lay. If Indridi met an old school friend in public, he could never tell whether the school friend was actually “serving” him. After some small talk (which, on reflection, did begin with the words: “Hi, Indridi, can I help you?”) the conversation generally ended the same way:

“It's clouding over,” said Indridi, “better get going.”

“Oh, that doesn't bother me, I've got an excellent umbrella. Can I offer you an excellent umbrella like this?”

“No thanks. There might be a thunderstorm. Don't want to be hit by lightning.”

“Oh, I've got such a great insurance policy with LoveLife. I got the umbrella as a freebie when I bought this great insurance policy with LoveLife.”

It was clear that the old school friend was a secret host and his conversation was slanted toward his goal of selling an umbrella or insurance. The offer was like a drain, and every single conversation was doomed to be sucked down that drain, regardless of what was originally being discussed.

Family:

“How's your mother?”

“She's fine, she's got such great life insurance with LoveLife . . .”

Art:

“What did you think of Jonas Hallgrimsson's poem?”

“I wonder what sort of life insurance they had in the nineteenth century. LoveLife hadn't been founded then . . .”

Sports:

“Good game yesterday.”

“Yes, poor Gisliâtorn ligamentâI wonder if he's covered for that. I'll look him up at LoveLife. You're insured with them, aren't you?”

It was difficult to distinguish a secret host from anyone else, so people didn't always know whom it was safe to believe and trust. A host could be anyone, even a member of one's own inner circle. Unlike traps and howlers, secret hosts advertised on their own initiative. A good secret host was careful not to give himself away and alternated products regularly. Some sold nothing directly; they merely advertised by creating the right mood or image.

“I recommend this

film

, you should go and see this

film

, it's supposed to be a really good

film

. I'd go right now.”

Secret hosts sometimes worked as spies and sent reports to i

STAR

(the LoveStar Mood Division's Image, Marketing, and Publicity Department). Only a handful of managers worked in the iSTAR office; the rest were cordless modern people, scattered around the globe, drawing their information from a database on Svalbard.

i

STAR

had no problem collecting basic information about culture consumption, television viewing, radio listening, food bills, musical tastes, daily journeys, main interests, and opinions, but more detailed information could come in handy. Hosts and spies twisted their conversations around to the company's interests, while i

STAR

experts got to be a fly on the wall. A discussion among a group of friends about love, death, God, or friendship could abruptly take a U-turn when the spy asked out of the blue: “Did you think the politician's tie was tasteful? What about his opinions? Do you sympathize with them? What about the last major international conflict? Do you remember how many civilians were killed? Would you put up with a greater loss of human life if you listened to more pop news? The president has a cute little cat called Molly. Do you find him more likeable now? What about the disabled? Are they fun? Would you take a cut in your standard of living in order to provide them with more services? What do you really think of Madonna?”

Indridi was on his way home that day, but no one said to him encouragingly: “Hello, Indridi! You're looking good today!” as he couldn't afford such luxuries. On the way up through Rofabaer he began to sing “Yesterday.” All the howlers in town were singing “Yesterday” at that moment; it was part of a publicity campaign for an international song initiative the following week. The song echoed round the town, but it was hard to tell who was singing voluntarily and who wasn't. It wasn't considered cool to be a howler, so many people pretended to be singing voluntarily by doing their best to look as if they were loving it. To most people, Indridi appeared a living, light-hearted advertisement. Their lenses showed the notes pouring from his head along with the lyrics, which hovered cheerfully in the air, and a message from the sponsor:

“Sing and be happy! International song week starts on Monday!”

When the song was over, Indridi had to fight back tears. Something unbelievably important had been struggling to emerge from his mind, but he had lost the thread when “Yesterday” began. His life was going to the dogs and everything was upside-down; only a few weeks before life had been as sweet as a strawberry, love as golden as honey, but now he wasn't sure that his love would be waiting for him when he got home.

INDRIDI WASN'T USED TO CRYING

Indridi wasn't used to

crying

. he had never really had any reason to cry. His life had gone smoothly and almost without a hitch since his rebirth. Most people agreed that he was a good boy, but it was virtually the only thing they could find to say about him.

“Indridi, he's a good guy,” said his friends.

Indridi was a fine, honest, promising kid who had received a good upbringing with decent parents in a tasteful house in the suburbs. He was lucky to be alive and owed it to the fact that he was born at a time of ethical uncertainty. When Indridi was born it was, for example, permissible to keep two frozen tubes containing spare copies of each child. If you had a child and lost it, you could resurrect it by having the same child born again using special “doctors” who undertook the “rescue procedures” (Chinese women, fertilized abroad, brought over in the eighth month of their pregnancy). Ninety-seven percent of parents who lost a child got over the loss within two years if they resorted to a spare, while those who had a different child recovered late or never. Those who resorted to a spare had, technically speaking, not lost a child; their child had had a narrow escape. Research showed that the long-term effect for the parents was similar to that of relatives of people who lost their memory. In reality the spares merely lost their memory and their lives were delayed by a few years.

But like all new technology, rebirth was inevitably overused and the rules were interpreted loosely by both individuals and businesses. The existence of spares made some people irresponsible, and Indridi's parents would probably have taken more care the first time he was born if it hadn't been for the spare copies held by the insurance company.

Indridi had not always been a good boy. He was a spare copy of the Indridi who had been born five years earlier. Of course, he had no memory of that period of his life, but his family showed him photos and home movies so he felt as if he remembered various things. The first time he was born he quickly became the most nightmarish child anyone had ever known. Not only was he naughty, he was also cheeky and foulmouthed from the first stages of language acquisition. His first word caught on film was “cunt.” Indridi was a liar, aggressive, easily influenced, and an intolerable crybaby to boot. He was diagnosed as completely amoral, egocentric, and incapable of empathy. He seemed incapable of “empathizing with emotional parties in his environment,” to quote the insurance company advisor's report following his four-year-old test. His mother had addiction problems at the time and was incapable of looking after children, while his father worked from dawn to dusk in the loading bays at LoveDeath. When he came home, more often than not stinking of “money” and wanting to “cuddle,” his mother had to knock back doubles to dull her sense of smell. On top of that they were inexperienced in bringing up children and at the insurance company's five-year-old test their parenting was judged a complete failure. The specialist compared the results to a computer model projected on the wall behind him.

“As you can see, it would take a major statistical miracle to save this specimen from bad company, drinking, smoking, vandalism, and drugs, and it would not surprise anyone if he took to crime at a very early age. Has he stolen anything from you?”

His parents thought.

“He often takes biscuits without asking,” said his mother.

“And once he took a cuddly kangaroo out of a toy shop and set off the alarm,” said his father. “But that was a year and a half ago.”

The child-development specialist continued, “All the findings indicate a downward trajectory. You can see that here in

3-D

.”

“Cool

3-D

,” said his father.

“It's new,” said the specialist smugly. He pressed a button and one of the bars in the bar chart began to move, grew hands and feet, danced back and forth across the screen, then took a pie chart and smashed it in the face of a fearsome-looking Venn diagram.

Mother and father laughed. “That was funny.”

“That big ugly bar chart is your boy,” said the child specialist sternly, and their laughter was abruptly silenced.

“Now I get it,” said the father. His target group was not mathematically inclined so the chart had to be lively and amusing for him to understand it. “Yes, now I get it,” he said again, to emphasize his words.

“What can we do?” asked the mother.

“You must understand that there is no way we can insure individuals of this type; the premiums would cost you both your annual wages. I'm talking here about the damage he will in all probability cause others. As far as he himself is concerned, he would be 100 percent liable for his own damages, with no health insurance.”

“That could become expensive,” said the father. Drug rehabilitation for a youngster who was not insured could cost as much as a family home.

“Are you sure he'll be that bad?” asked the mother.

“I could show you examples all day. Nearly every prisoner in the city jail got better marks in his five-year-old test than your boy.”

“But we're working on him,” said his father. “We're finally taking a vacation together, and I'm quitting LoveDeath this summer and starting a job at i

STAR

. We're getting ourselves sorted out. Can't we just have a review this time and then see how his six-year-old test goes?”

“As you can see, not a single child has reached adulthood unscathed when burdened by statistics like these. By six he could already be causing untold and irreparable damage.”

Once this would have been counted as a final, statistical death sentence for Indridi because the research results did not lie. They were based on the most stringent assessments, psychiatric personality tests, and astrological charts. But Indridi had had the great luck to be born at a time of uncertainty when no one knew any longer exactly how to define an individual. Individuals must make their own definition of the individual, said individualists, and so the matter was settled. The insurance company offered Indridi's parents a unique opportunity to learn from experience and “rewind.”

“We can offer you the opportunity to rewind around five years and then you can make an effort from the outset to protect the individual from lifelong unhappiness. Wouldn't it be better to rewind now and ensure one hundred years of happiness rather than get stuck with ninety-five years of misery? In reality he'll gain five extra years. Wouldn't you want to add five years to your own life if you were offered the chance?”

Indridi's mother was a bit doubtful, but it was the same lecture she had heard from most of her friends. She'd lost count of all the old ladies who had taken umbrage at Indridi's bad language and snapped: “Why hasn't this child been rewound and taught some manners?”

“Are there no other options in this situation?” she asked. “We really wanted to get the upbringing over and done with before our fiftieth birthdays. We've been paying installments on a world cruise.”

The specialist leaned over the table with a grave expression. “People have sued insurance companies abroad because this opportunity was not exploited. A man in England was sent to prison when his son murdered an old woman. During the investigation it emerged that he had been repeatedly offered the chance of rewinding the boy but had been too stubborn. So it was actually his fault.”

“When could we ârewind'?” asked the father.

“According to the definition of the individual that you have selected and the spare copies that were filed at the time, your boy could get a new life in ten months' time, as soon as the end of October. Of course, the premiums will go down immediately as a result, which will weigh against the cost of the procedure.”

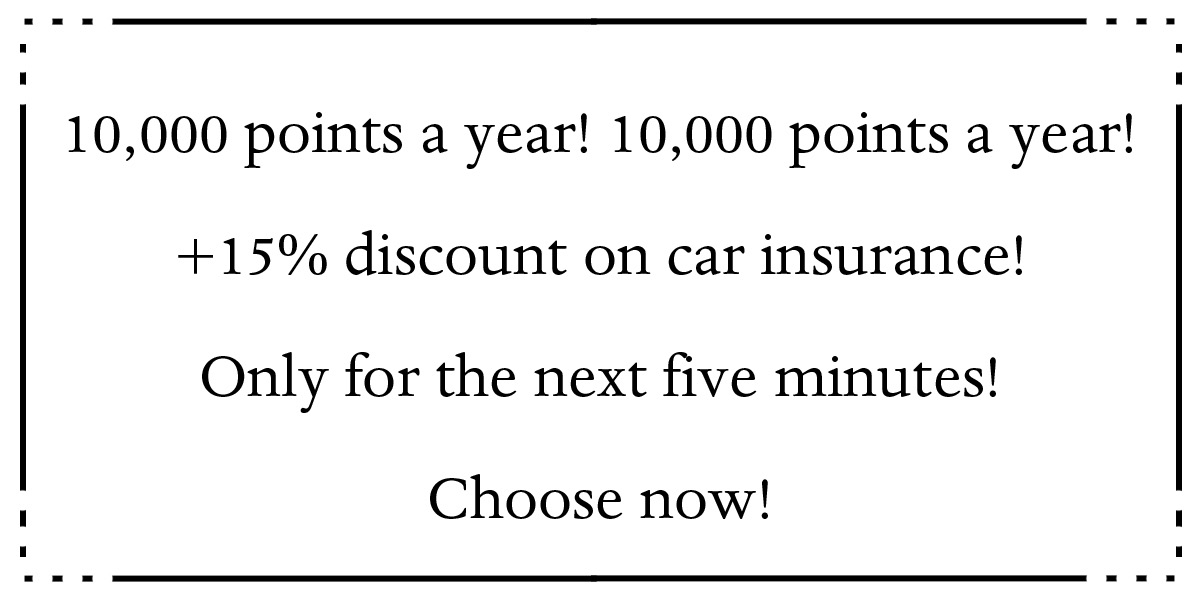

On the wall the dancing bar chart was now replaced by a flashing sign:

Mother and father looked at one another while the clock on the wall counted down. The ideology suited cordless modern people, and they had been brought up with the concept since childhood. It was like wiping a hard disk, or starting a computer game with three lives so that when things went wrong you could always start over.

“As soon as this autumn, yes,” said his father, looking through the glass wall to where Indridi was chewing the head off a Barbie doll.

“But then he wouldn't have the same birthday, would he?” said his mother. “His birthday's in February. Won't it be difficult for him to adjust to the change?”

The advisor demonstrated to them how Indridi would get on better under a different star sign. His faults in Aquarius would turn out to be positive advantages in Scorpio. His aggression would emerge as determination and perseverance instead of erupting at regular intervals as an outlet for repressed rage and introverted feelings. As a result, instead of being quick-tempered, irritable, and impatient, he would be hypersensitive and painstaking under a star sign that suited his genetic makeup.

“He's got his father's temper, but that's not seen as a disadvantage in your family unless the star sign conflicts. In his case it's like oil and . . .”

“Fire?” said his father in consternation.

“FIRE!” yelled his mother. Indridi stood in the middle of the room behind the glass wall, the doll in flames.

“How did he get hold of a lighter?”

His father stamped on the remains of the Barbie doll and the melted plastic stuck to the soles of his shoes.

“INDRIDI, REALLY!” yelled his mother, chasing him round the room. “DO AS YOU'RE TOLD, INDRIDI! COME HERE AT ONCE!”

“This autumn?” asked the advisor, looking at the clock. He had got up and was now standing in the rays of the projector, “10,000 points” flashing on his forehead. The countdown had reached twenty-nine seconds.

“This autumn!” shouted the father as he pursued Indridi down the corridor.

The wait for autumn proved hard. Especially during weekends when Indridi wasn't at school. Finally the day of his “rewinding” came, and the advisor greeted them with a smile. Indridi was wet-combed and dressed in his Sunday best with a blue bowtie.

“Where am I going, Mom?” he asked.

“You're going through that door,” she said, pointing to a black door, “then you'll come back out of that white one, and it'll be your birthday and we'll give you a present.”

“Goody,” said Indridi, “thanks, Mom,” and kissed her on the cheek before being led by the advisor through the black door.

Before his mother could utter a word, there was a sound of joyful singing from behind her. A nurse and the advisor carried Indridi out through the white door. His face was red and rumpled and his body covered in white birth fat. He was bawling.

“He weighs nine pounds and four ounces!” said the nurse with a tender smile. “Congratulations. Hopefully he'll get on better now.”

“Oh, he's so tiny,” said his mother, her eyes filling with tears.

She took him in her arms and Indridi soon stopped crying when his mouth was plugged with a bottle.

“Here are his clothes,” said the advisor, passing them his folded Sunday best.

“Where's the blue bowtie?” asked his father, glancing around, but the insurance advisor pretended not to hear him.

“This is a fine boy! He'll soon grow into his clothes again.”

For whatever reason, Indridi's upbringing succeeded much better this time around. His mother went into rehab and his father started as a service rep at iSTAR and so no longer stank of his job. Indridi received extra special care, attention, and rewards for being well behaved and good. He was made to watch film clips showing that he had once been naughty and bad and what would happen if he didn't learn from the experience.

“That's what you were like on your last fourth birthday,” said his parents and showed him a home movie in which he was bashing his little cousin over the head with a plastic sword. “You must be good now.”

“Otherwise we'll have to start you all over again, Indridi son,” said his father. “We'll get there even if it takes twenty years for you to become a good, well-behaved ten year old!”

Indridi was determined to do well and feared nothing more than the third test tube, which was waiting to take his place. He never felt truly secure, never felt he did well enough, and always wanted to do better (thanks to his Scorpio star sign). He was in perpetual competition with Indridi number three, who could no doubt outdo him in anything he turned his hand to. His parents were a great support to him and from them he received precisely the amount of love and warmth that research demonstrated was necessary for children. His father was proud of his son but never completely satisfied and so encouraged competition with number three.

“Amazing,” his father might comment from behind the morning paper, “if you had been born today we could have used these exciting new theories. Look! They result in a 30 percent increase in reading speed, 9 percent greater emotional maturity, and 18 percent improved concentration. Look how exciting the school syllabus for eight-year-olds is nowadays! The kids stay in school till seven in the evening.”