LoveStar (5 page)

Authors: Andri Snaer Magnason

Tags: #novel, #Fiction, #sci-fi, #dystopian, #Andri Snær Magnason, #Seven Stories Press

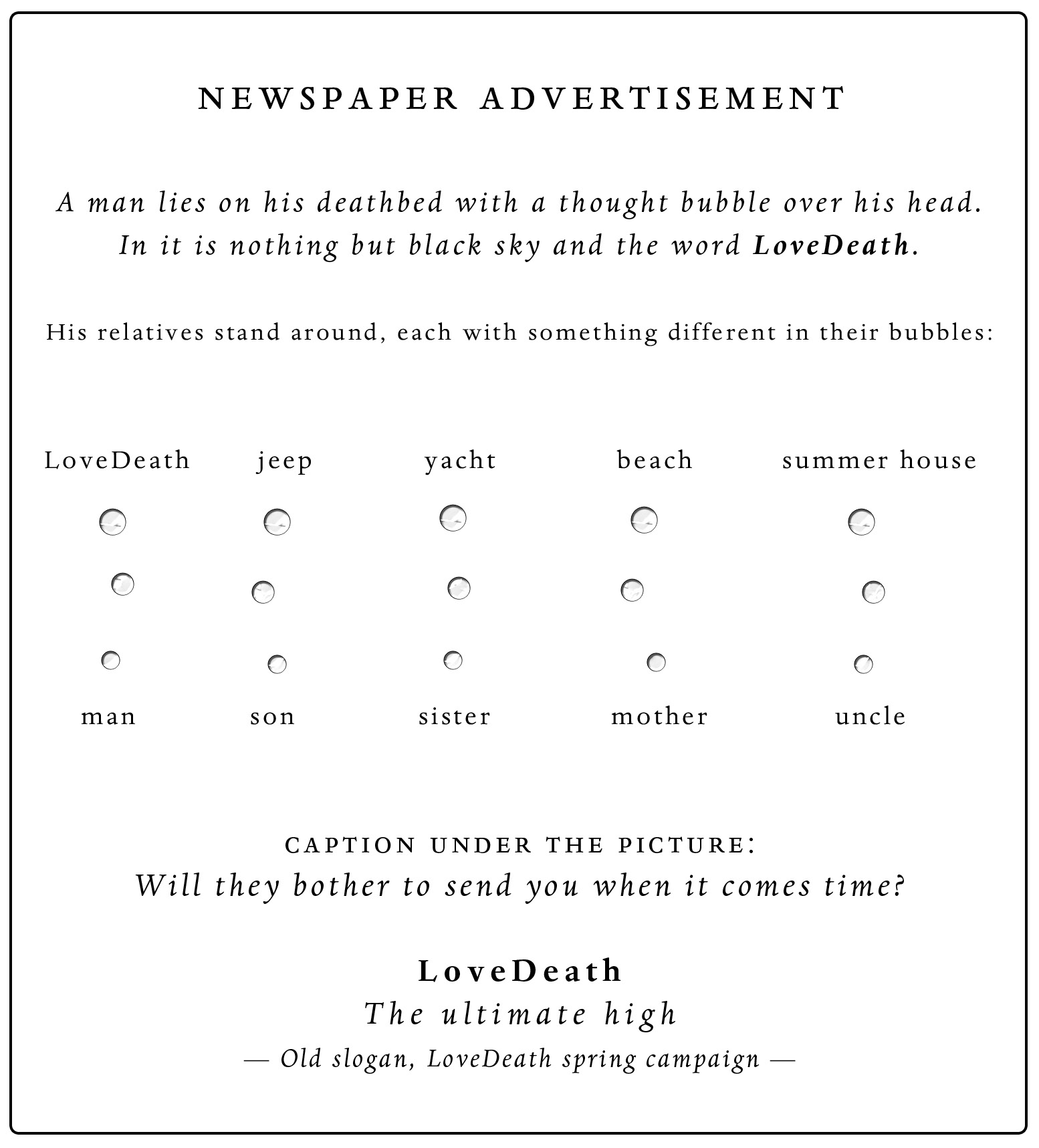

Creeping worms and grinning skulls became forever linked to the old method in people's minds after a successful advertising campaign in the early days of LoveDeath. The campaign's flagship was the award-winning advertisement

Rotting Mother

:

The first year beneath the soil is shown speeded up. A young mother is lowered in her coffin into a cold grave; her beautiful body blows up, turns blue, and rots, and in fast-forward her body seems to know no restâit writhes and swells and her face is gnawed away by maggots until her corpse seems to scream. Then came the new method:

CLEAR SKY

SHOOTING STAR

LOVEDEATH

The clean method. Cleanness mattered. A simple, beautiful idea. LoveDeath was beautiful and the concept was easy to grasp even for children who couldn't understand why someone who was supposed to go to heaven should be buried in the ground.

Child: Mommy! Where do the bad people go?

Mother: They go to hell.

Child: Where's hell?

Mother: Hell's under the earth.

Child: Is Granny going to hell, then?

Mother: No, she's going to heaven.

Child: Why was she put in the ground, then?

Mother: Oh, you'll understand when you're older.

Announcer: LoveDeath, now everyone can go to heaven for only thirty thousand points* (*per month for twelve years)

LoveDeath: The high point of life!

Ââ Dramatized radio advertisement â

The old method paled in comparison to LoveDeath. How can your granny, who's underground, buried in hell, be soaring in heaven like an angel? No, it didn't make sense. The old idea was not clean. The explanation was too far-fetched: the substance here, the spirit there. Was that an appropriate end to a beautiful life? To be lowered into a cold grave? To send your loved one to their final rest in a place where you would not feel easy for one moment on a dark night? To make your love rest in a place that was forever linked to darkness and horror? Who wanted to invest in decomposition? The matter was simple: the old idea was bad. The ceremony uncomfortable. The decomposition disgusting. It was hopeless from the start, a bad idea that was called tradition because no one had thought of anything better for sixty thousand years. No flowers or wreaths, please. Those who wished to remember the deceased were invited to donate their money to a more worthwhile cause. Death had potential that no one but LoveStar picked up on.

LoveDeath was initially the preserve of billionaires. In Hollywood LoveDeath was the next step when the plastic surgeon admitted defeat and said he couldn't correct the wrinkles, eye-bags, varicose veins, cellulite, and droopy breasts; it was all downhill from now on and this was the right moment: to have yourself fired to the climax of life, submit to LoveDeath. The ultimate way to burn fat.

Death is clean and LoveDeath is the purifying fire. Before becoming one with eternity you will burn up in the atmosphere. Then the spirit will be released from the bonds of the flesh.

âExcerpt from LoveStar's farewell address

on the launching of Pope Pius III

During the early years it made world headlines whenever anyone was fired with LoveDeath, and tourists and fans thronged to see the launch. But LoveDeath became so popular that the service improved, the cost came down, and the quality rose.

The old method cost a million points or even two and hadn't changed for sixty thousand years. It wasn't long before LoveDeath became competitively priced; it was no longer one thousand times more expensive than the old method but only one hundred times more expensive, until eventually it was only ten times more expensive and that was when its operations really began to expand at a furious rate. In the end LoveDeath cost less than sending four hundred pounds of fresh fish to Japan by airfreight.

Of course, LoveDeath didn't appeal to all target groups at first, but by the time LoveDeath had become cheaper than the old method and Larry LoveDeath was introduced, it was no longer a question of appeal. LoveDeath was more economical, and more beautiful, and children wouldn't hear of anything else. Big stars elevated themselves above the masses by being fired in fantastically expensive costumes of precious materials that burnt at different temperatures:

ORDER

Magnesium outer layer to burn with a white flame, then a yellow layer of a sulfur compound to burn with a reddish-yellow blaze, then a pale-green layer of copper sulfate to burn like green glitter, then underclothes of a compound 60 percent polyester and 40 percent cotton to burn like a rainbow, and finally the body itself in its naturally sun-white blaze until two silicon pads explode like fireworks.

â Order for Pam An who fell so memorably over Hollywood after dying during plastic surgery at only fifty-three years old â

Colorful LoveDeaths were fantastically expensive exceptions and no one failed to notice them. Most people had to be satisfied with the natural blaze.

You could say that Sigrid owed her life to LoveDeath. Her mother was a fifty-five-year-old rocket engineer and had provided Sigrid and her sister with a stylish, well-designed home. When she told her daughters about the early years of LoveDeath, she closed her eyes and spoke about the glow and the mood and the novelty. LoveDeath was like the herring boom, and everyone in her generation was affected by LoveDeath nostalgia and pioneering arrogance.

“You might at least thank us. We were the ones who built all this up.”

There was some truth to this. When the expansion was at its height and LoveStar was asked how many of his countrymen were on his payroll, he answered: “I guess about half.”

Of course, the glow was greatest during the early years, while serious stars and millionaires were being fired with the appropriate media circus, retinue, and glamor. At that time most LoveDeath employees were young and up for fun and overtime. The best parties were held up north at LoveDeath, and it was at one of these very parties that Sigrid had been conceived. Her mother had sneaked out into a hollow with an electrician from Nordfjord while a wrinkled pop star with varicose veins sang an old hit in return for a trip with LoveDeath. Everyone drank to the star and thanked her for the swan song as leather-clad backup singers (from LoveDeath's female-voice choir) dressed her in a silver-leaf evening dress over an aluminium boiler suit. They led her out to the next rocket and, as Sigrid's parents rolled around in the heather, the flare lit up the summer night and the fine rain settled like dew on the flowers in the valley.

LoveDeath was ubiquitous. Every day LoveDeath transport trucks drove the day's harvest of the dead from the world's cities, and every minute a ship or plane set off with a full cargo, heading north for LoveDeath. Black freighters under Caribbean flags sailed to the country laden to the sinking point with corpses from every continent. The sky was striped white until late in the day after black jets had brought the European consignment. Russian airships hung over the country like black air-melons, carrying five thousand bodies with every trip. While the airships were being filled with helium their captains could never resist inhaling, ringing up a comedy radio show, and talking like Donald Duck in Russian.

LoveDeath was fabulous but could also be a bit eerie, especially in November and December when few living people made their way to the country, and some (for example people in the sensitive target group who cry over sad films) found it depressing seeing nothing but buses packed with Chinese or Swedish pensioners flocking in convoys north to LoveDeath, knowing for sure that none of them would return home alive.

Anyone worth their salt had been involved in LoveDeath or connected to it in some way. Fifteen thousand pilots flew LoveDeath aircrafts and eighteen thousand captains sailed people to the country and fished up the rockets that they came across out at sea. These were reused again and again. Two thousand bus and truck drivers drove customers north. Thousands worked in marketing, sales, packing, and distribution, even more in loading, calculation of firing coordinates, construction of new launchpads, and energy acquisition for increased hydrogen production. LoveDeath was insatiable as far as energy was concerned. All lines lead to LoveDeath, as the proverb said. Wind farms were erected out at sea, tides were harnessed, and geothermal heat fetched up from the magma chambers beneath volcanoes. All this was used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen and drive the simple chemical reaction: 2H2O g 2H2 + O2.

During the early years growth was frighteningly rapid and there were often squabbles over the proceedings. Sometimes the freezer units on the container ships broke down and a ghastly stench was released when the holds were opened. Then everyone held their noses, but the people living in the ports were used to this and called it the smell of money. In the worst cases the cargo ended up as guano, but iSTAR made sure that the news didn't get out. Relatives never learned that what burnt so beautifully in the night sky was not their loved one but two hundred pounds of horsemeat.

The country may have been the center for death, but its image was as positive, profound, and clean as LoveDeath. In the world press the country was called the Ganges of the North and perhaps there was something in it. The country was Ganges, Bethlehem, Mecca, Graceland, or whatever they were called, rolled into one, all those holy places men had to visit before death. LoveStar could convert anyone to his cause. He managed to unite everyone under LoveDeath, whatever strange ideas people had about religion or death. When Indian gurus were launched, they were fired with electrolyzed water from the Ganges. When popes and bishops were launched, holy water was used, while Faroese oil barons were launched in monster spacecrafts driven by the crude oil that they had brought with them in tankers.

A large number of countries around the world wanted to offer LoveDeath and share in its operations, but the patent was held by the LoveStar corporation and no one could compete with the facilities at the LoveStar theme park in Oxnadalur. The deserts and reservoirs in the highlands and the immense heaving sea around the country made it unlikely that unsuccessful launches would land on towns or cities. The deciding factors were the inexhaustible reserves of clean, renewable energy and an endless supply of fresh water to split into hydrogen and oxygen, and then the rest was simple: Electrolysis! Load! Fire!

When the hydrogen burned there was no foul reek, only a clear water vapor that formed a mist on the northern moors. Although people were launched into the sky from the peaks around Oxnadalur, the stars could fall to earth anywhere on the planet. All around the globe convoys of vehicles wound up hills and mountains, and people sat silent and thoughtful around crackling campfires waiting for their loved ones to fall to earth in a blaze.

DON'T BREATHE

LoveStar sat in the plane, taking care not to crush the seed. He opened his hand and held it from him like dust that you mean to blow away, yet he hardly dared breathe in the direction of the seed.

He had become isolated from other people in the company lately. Almost the only people he had contact with were Ivanov, head of LoveDeath, and Yamaguchi, head of the Bird and Butterfly Division. Nowadays he saw little of the heads of other departments; they had made themselves comfortable on Pacific islands. He met them only at video conferences, but in recent weeks he had not bothered with most meetings. Now he was quite out of touch with the world. No film clip on the lens, no music in his ears. He looked at the seed with his naked eye.

He knew what ideas were making the rounds at the Mood Division and knew better than anyone that nothing can stop an idea. He was confident in his ability to stand up to them, but what would they do with the seed when he was dead? What should he do with the seed himself? He had been responsible for the search and expected to find a cave, ancient artifact, mountain, mound, pool. But a seed? What does one do with a seed? What would germinate from this seed?

A seed becomes a tree?

A seed becomes a flower?

All as the one flower.

The search for what turned out to be a seed had taken seven years. Over the last few months LoveStar had spent most days at the office, waiting for the search party's reports. He did calculations to keep his brain working. He had to keep his mental pathways open. He drew patterns or a landscape. Always similar patterns and the same landscape. When he was in the grip of an idea he generally tried to preserve his mental health by doing calculations or drawing. Drawing was a form of meditation or overflow, an outlet for an unborn idea. He was also a collector: in his youth he had collected samples of handwriting from everyone that he could get hold of, even from abroad, as well as knucklebones from every kind of land animal, otoliths from every species of fish, and wings from every kind of bird, and the office was crammed with all these things. He had a yellow or fluorescent ring round his pupils, which shone in the dark like cat's eyes. He looked out over the unspoilt Oxnadalur valley. The office had a 360° view with windows on all sides, yet seen from the outside it was a black lava peak.

LoveStar's collecting mania had cranked up. He collected the world. He never acknowledged the fact himself, saying the world wanted to come to him. Above the valley hovered a red helicopter from a Norwegian oil rig marked Statoil. For a moment he mentally tried out his star on the helicopter with the legend below: LoveOil. He sent a short memo to the computer at iSTAR's asset management department: Statoil/LoveOil? Nothing more was needed. The computer would investigate the question, and if it proved profitable the computer would buy the company and simultaneously print out sticky labels marked LoveOil.

Below the helicopter hung a tarred stave church. A gift from the Norwegian state to LoveStar's Museum of the World. The gift was thanks to the Mood Division. They had managed to convince the world that anything not on show in the Museum of the World was worthless. Further down the valley the road had been closed and waymarkers and signposts had been removed while a giant Sphinx made slow progress up it on the back of a truck. All these things were on their way north to the vaults under LavaRock, and the magnetic pull of the LoveStar theme park seemed infinite. Infinity: â. He drew the symbol on the paper again and again. Infinity. He owned an infinite amount. He had waited an eternity, an infinite time, for the results of the search. An infinite sum of money had gone into financing it. If it all worked out, something infinitely great would be found. He turned the paper around and drew the infinity symbol over those already drawn on the page until the paper was covered with flowers.

LoveStar let his eyes wander over his realm. Polish welders snacked on Prince Polo crackers in one of LoveDeath's rocket hangars; a trawler hauled a rocket up from the heaving sea; a long-haired fly specialist from the Bird and Butterfly Division sat intently measuring the density of a mosquito brain while a colleague talked into thin air, apparently painting an invisible wall. In a concert hall on the outskirts of Bangkok, fifty thousand moodmen were disco-dancing at an international incentive conference held by iSTAR's press department. A crazy hubbub of rejoicing broke out and the moodmen flung their arms wide as if in a trance. LoveStar switched perspectives and saw what was happening. Ragnar Ã. Karlsson, former head of mood at iSTAR, was beaming at them from a giant screen and singing a duet with a stark-naked female pop singer in a live broadcast from the seventy-thousand-strong iSTAR music department conference in Moscow. LoveStar ground his teeth. There was no sign of Ragnar's standing within iSTAR diminishing, even though he had been demoted to head of the LoveDeath Mood Division.

LoveStar looked closer to home, watching a raven soaring on an updraft by the cliff, before passing inside the rock to where tourists were being shown to their rooms. In the inLOVE wings of the theme park, endless rows of lovers from all over the world could be seen cuddling up together inside the cold rock walls. Old people sat in rocking chairs, waiting for LoveDeath, resting their eyes on 3-D images of their childhood homes, or watching rocket after rocket shoot into space.

LoveStar roved around the world in this manner, changing perspective from Paris to Tierra del Fuego to Bologna, Tokyo, and Kiev. Everywhere towers rose like anthills from the suburbs and loomed over the old city centers. Although the towers were built variously from steel, stone, glass, or carbon fiber, the brand was instantly recognizable. They were imitations or stylizations of LavaRock, erected where there had once been cemeteries before LoveStar had taken it upon himself to “clean them up” and free the cities once and for all from “los miserables restos de la época de descomposicion de los cadaveres de ceres humanos,” as the Mayor of Buenos Aires put it: “The pathetic remains of mankind's age of decomposition.”

LoveStar went nowhere near the daily running of LoveDeath. In a documentary about LoveDeath on CNN, LoveStar had said: “The satisfaction of seeing LoveDeath become a reality and watching Elizabeth II fired over Windsor Castle lasted for one day. It lasted from the first rocket being launched at six in the morning, until Elizabeth fell to earth at 3:00 am the following morning. The moment the flash faded I became superfluous. Universities produce people in the tens of thousands who can, want, and know how to keep LoveDeath running and expanding. I had the sense to give them free rein.”

That wasn't to imply that LoveStar didn't make demands on his people: “WHAT THE HELL DO YOU MEAN MICK JAGGER WAS BURIED?! HE HAS A SEAT RESERVED WITH LOVEDEATH AND IF HE DOESN'T GO UP ONE OF YOU WILL GO IN HIS PLACE!!!”

The cleanup job and tower buildings in the big cities were entirely the responsibility of Ragnar Ã. Karlsson and the LoveDeath Mood Division. LoveStar roved from tower to tower and then rang Ivanov, head of LoveDeath.

“Have you found out what's supposed to go in those towers?” LoveStar asked.

“Don't worry, it's a safe project.”

“But what are the towers supposed to house?”

“Hotels, offices, or shops, I expect.”

“You expect?”

“This is the most valuable real estate in the cities and it's almost self-evident that the towers will house these kinds of businesses. Anyway, it's 100 percent Ragnar's baby.”

“So you're not sure? I want to you keep a close eye on him.”

“I can't stick my nose in everything. I had the sense to give Ragnar free rein. It's worked out well, as you can see.”

“What about the cost?”

“The profit from the cleanup job covers the cost in full, and the bodies can go straight to the Million Star Festival.”

“So you were paid for the bodies, got the land thrown in, and now you're supposed to sell the space in the towers?”

“I'm telling you, he's a brilliant moodman, Ragnar, unbelievably brilliant. The cities paid tenfold for the bodies, due to the decomposition, you see, and the Million Star Festival is a bonus. It's a mood boost, a pure image boost. It was a good idea of yours to transfer Ragnar over to us. I never dreamed that I'd live to see boomtime again at LoveDeath in my old age.”

“So everything's going well?” asked LoveStar skeptically.

“The Million Star Belt is visible to the naked eye. Take a look.”

“I'll look at it this evening.”

“It's visible by daylight,” said Ivanov.

LoveStar went over to the window and looked up at the sky where there was a gleam from something that lay like a broad arch over the vault of the heavens, like a stripe of glittering, powdered glass, like glitter or fool's gold on a riverbed. He picked up a telescope to see better. It was like a dense shoal of herring swimming far above the clouds. He switched perspective to the LoveStar satellite telescope. He shuddered at the sight that met his eyes: an endless shoal of LoveDeath orbiting the Earth, a hundred million gleaming silver bodies forming a Saturn-ring right around the globe!

“Isn't it fantastic?” said Ivanov. “It's equivalent to six years' worth of deaths.”

LoveStar gulped, closed his eyes, and tried to breathe evenly. Ragnar had certainly not given up.

“Are you okay, by the way?”

“Yes,” said LoveStar.

“You've been a bit preoccupied. You should talk to Ragnar more. I don't understand what you've got against him. Damn it, I reckon you've got an heir in that boy. It's time to let the youngsters have a go. It's not as if we're immortal.”

LoveStar didn't answer.

“Hello? Are you there?”

LoveStar looked at the sun. It was sailing behind the Million Star Belt, its light reflecting from the shoal and forming a halo, a shining circular double halo with an additional sun to the east and another to the west. Two blazing red extra suns in the sky, like a burning sunset reflected in the western windows. “Three suns,” thought LoveStar.

“Are you still there?” asked Ivanov.

“

Three suns in the sky: a sign that evil is nigh,

” thought LoveStar.