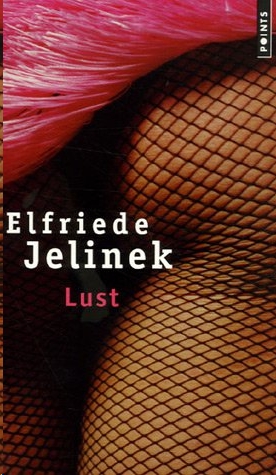

Lust

Authors: Elfriede Jelinek

The translator would like to thank Martin Chalmers and Dorle Merkel for their

helpful advice

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 91-61209

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British

Library on request

The right of Elfriede Jelinek to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright© 1989 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg Translation Copyright © 1992 by Serpent's Tail

Originally published in German in 1989 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH First published in English in 1992 by Serpent's Tail

4 Bldckstock Mews, London N4 2BT website: www.serpentstail.com

Typeset by Contour Typesetters, Soulhall, Middlesex Printed by Mackays of Chatham, pic

This translation received financial support from the Commission of the European

Community, Brussels

1098765432

LUST

by Elfriede Jelinek

CURTAINS VEIL THE WOMAN in her house from the rest. Who also have their homes. Their holes. The poor creatures. Their hideaways, abideaways: their fixed abodes. Where their friendly faces abide. And all that distinguishes them is the one thing that's always the same. In this position they go to sleep: indicating their connections with the Direktor, who, breathing, is their eternal Father. This Man dispenses truth as readily as he breathes out air. That is how much his rule is taken for granted. Right now he has just about had it with women, so he says. See, there he is, yelling that all he needs is this woman. His woman. There he is, as unknowing as the trees all around. He is married. The fact acts as a counterbalance to his pleasures. This Man and his wife do not blush in each other's presence. They laugh. They have been in the past, are now and ever shall be all things to each other.

The winter sun is small at present. It is depressing an entire generation of young Europeans growing up around here or who come here for the skiing. The children of the workers at the paper mill: they might well recognize the world for what it is at six in the morning when they go to the cowshed and suddenly become strangers terrible to the animals. The woman goes for a walk with her child. She alone is worth more than half the bodies around here taken together. The other half work for the Man at the paper mill when the siren howls. And people keep a tight hold on what's closest, what's stretched out beneath them. The woman has a large clean head. She goes out walking with the child for a good hour, but the child, intoxicated with the light, would rather be rendered insensate, insensitive. By sport. The moment you take your eyes off him, he's plunging his little bones into the snow, making snowballs

and throwing them The ground gleams with blood As if served up fresh. Torn birds' feathers on the snowy path. Some marten or cat has been going about its natural business, slinking about on all fours, and some creature or other has been gobbled up The carcass has been dragged off. The woman was brought here from the town, to this place where her husband runs the paper mill. The Man is not counted one of the local people; he is the only one who counts. The blood spatters on the path.

The Man He is a largish room where talking is still possible His son too has to start learning to play the violin now The Direktor does not know his workers as individuals. But he knows their total value as a workforce. Good day there, everybody! A works choir has been established. It is funded by donations. So the Direktor has something to keep him occupied. The choir travels everywhere in buses, so people can say, that's terrific. Often they have to take a stroll round little provincial towns. Off they go, with their unmeasured strides and their measureless wishes, gaping at the provincial shop windows. In the halls, the choir offers a front view of itself, its rear view turned to the bar When you see a bird in flight, all you set is the underside, too. Taking deliberate, industrious strides the songbirds ooze forth from the hired bus, which is steaming with their dung, and promptly try out their voices in the sunshine. Clouds of song rise beneath the mantling sky as the prisoners are lined up

Meanwhile their families are getting by without Father, on a small income. The Fathers eat sausages and drink beer and wine. They damage their voices and senses by using both without due care. A pity that they are of humble birth. An orchestra from Graz could take the place of every one of them. Or alternatively give them back-up. Depending what mood it was in. These awful feeble voices, cloaked in air and time. The Direktor

wants them to use their voices to beg for his benevolence. Even the lowly have a chance with him if he notices that they have musical talent. The choir is the Direktor's hobby and is looked after accordingly When they are not being driven about the men are in their pens. The Direktor invests his own money when it's a matter of the bloody, stinking qualifying rounds in the regional championship. He assures himself and his singers of permanence, of continuation beyond the fleeting moment. The men, built above-ground and still building still building. So that by their works shall their wives know them when they are pensioned off But at week ends these most divine of creatures come to a weak end they don't climb the scaffolding, they climb onto a dais at the pub, and sing under compulsion, as if the dead might return and applaud The men want to be bigger, greater and lo. all their works and words want the same thing Edifying edifices

At times the woman is dissatisfied with these defects that burden her life: husband and son. The son a full colour copy, a perfect reproduction, a unique and photo-graphable child He runs along after Father so that he too will be a man one day. And Father )abs the violin in position under his chin so the foam well and truly sprays from his teeth With her life the woman answers for the smooth running of their enterprise and for good feelings each to each Via this woman the Man has passed himself on to perpetuity The woman was of the best stock that could be found and has passed herself on to the child. The child is well-behaved, except al sports, where he is allowed to run wild and needn't put up with anything from his friends, who have unanimously chosen him as the ladder to the heaven of full employment His father sees to it that he himself won't pass away from the earth He manages the factory and manages his memory, rummaging in the pockets of memory for the names of workmen who try to get out of singing in the choir. The

child is a good skier, the village children are like grass beneath him. There they stand beside their shoes. The woman in her daybag, which is washed out every day, no longer goes on stage, no, she provides the child with an anchorage on her blessed coast, but the child is forever running away, taking his fire off to the poor people who live in the little houses. Intending them to find his vivacity contagious. In his fine garb he will glide across the whole world. And Father is as puffed-up as a pig's bladder, he sings, plays, yells, fucks. The choir does as he wishes, roaming from valley to mountainside, from sausage to roast, singing likewise. Never asking what they're getting paid for doing it. But the choir members are never laid off. The house is so bright that it saves on lighting costs! Indeed, its brightness is better than light. And song makes a happy home.

The choir has just arrived. Older indigenous peoples out to escape their wives. Sometimes the wives are there too, their locks stiff (sacred power of hairdressers in the country, salting these beautiful women with great pinches of permanent waves!), they have alighted from the vehicles and are having a nice day out. The choir, after all, cannot simply sing to light and air. Calmly the wife of the Direktor walks to the front on Sundays. In the village church. Where God, the mere sight of whom in pictures is an outrage, talks to her. The old women kneeling there already know what lies ahead. They know how it all ends. But still they haven't managed to find the time to learn a single thing. They work their way round from station to station of the cross, and for what? So that soon they can meet their maker, the Lord God Almighty, that hallowed member of the trinity of airhead godhead, face to face. Their slack-skinned bellies in their hands to prove their worthiness to be received. At last, time stands still. Hearing breaks loose of the detritus of a lifetime's

perception of their lot. Nature is beautiful in a park and so is singing in an inn.

Amidst all these surrounding massifs to which athletes come the woman realizes that there is no stable centre in her life, not even a recreation centre where a life of recreation might be waiting. The family can do good. But it expects to eat good food too. And to bag the quarry on feast-days. The loved ones are so fond of Mother. There they all sit, together, blissful. The woman talks to her son (bacon infested with the maggots of love) and fills him with her all-pervasive low and tender shrieking. She is concerned about him. Protects him with her soft weapons. Every day he seems to die a little more, the older he becomes. The son takes no pleasure in Mother's griping and promptly demands a present. Brief transactions such as these, transactions involving toys or sports equipment, are their way of trying to communicate. Lovingly she flings herself on her son, but even as a torrent she simply flows away, to be heard somewhere far beneath him, in the depths. And she has only this one child. Her husband comes in from the office and instantly she hugs her body in tight so that the Man's senses will not scent a bit of what they fancy. Music sounds forth, straight out of the baroque era and the record player. Imperative: to resemble the full-colour holiday snaps as closely as possible. Not to change, from one year to the next. There isn't a single truthful word in this child, I swear; all he wants is to be off skiing, you take it from me.

Outside feeding times, the son talks very little to his mother, even though she beseechingly pulls an intimate blanket of food up over the two of them. Mother tempts the child out for a walk. And ends up paying dearly, by the minute. Listening to this neatly-turned-out child talking like a television. Which is his main source of nutrition. Off he goes now, out for a walk, unfearing,

because he hasn't been watching the nastiness of the videos yet today. At times the sons of the mountains are already asleep at eight in the evening, while the Direktor is adeptly filling more art into his engine. And what most puissant of voices is it, pray, that bids the herds'in the meadow be upstanding, each and every one? And likewise the poor and weary early in the mornings when they look across to the opposite bank where the rich have their holiday homes? I think it's called 03 Wecker. Playing one hit after another from six a.m., those busy little rodents, gnawing away our days from the moment we wake.

In the Hitlerian back rooms at the gas stations they are taking a swipe at each other again, the petty people tied up in apron strings, wasting themselves and their half portions of ice cream beneath colourful umbrellas. It is always over so quickly. And work takes so long and the rocks endure for ages. No matter how endlessly they go on repeating themselves, all these people can do is reproduce. The hungry mob. Yanking its sex out of that door so conveniently positioned up front. These people don't have windows, so that they don't have to look at their partners when they're at it. We are kept like cattle! And there we go, worrying about getting on in the world!

On the ground lie peaceful paths. In the family there is always one who is waiting in vain, or falling in the struggle to stake a claim. Mother's labours afford her a sense of security, which the fruit of her labour, bent over his instrument, promptly destroys. The local people don't feel at home here, they have to retire for the night when evening life awakens good and proper in the sporting people. To them the day belongs, to them the night belongs as well. Mother monitors the child, squatting on the wall where she lives, so the child does not feel too comfortable about things. This violin doesn't

particularly care for the child. In the catalogues, all the like-thinking crowd stride out defiantly, intending to fill each other's cups to overflowing. The personal column is read, and each person rejoices in his own little night, cast into the dark of an unfamiliar body. The diligent carpenters of life put ads in the papers, hoping to install their partition walls in other people's dark corners. One man on his own ought not to be too much for himself to handle! The Direktor reads the ads and places an order for his wife so that he can order her to her place, which is in red nylon lace with holes in the silence for the stars to peep through. One woman isn't enough for the Man. But the threat of disease restrains him. Prevents him from putting forth his sting and supping honey. One day he will forget that his sex can be the end of him and he will demand his share in the great harvest. We want to have fun! We want to ramify! The people who placed the ads lie in complicated positions on their mattresses, describing the paths along which they dally. It's to be hoped their fires don't go out; that would mean they would have to go out themselves and court disappointment. His wife is not enough for the Direktor, but still, he's a public figure, and he has to make do with this small car. He tries to make the best of it: to live and be loved. The children of people who're there to be used: they themselves are employees in the paper mill (it is a temptation to them, the unbound product of which bound books are made), they are unlovely to look at. It takes a siren howling at them to produce any sign of life. At the same time they are hurled out of life and fall like cataracts, superfluous, from the lofty heights of their savings. The helm has already been seized from their hands and in their stead their wives are making for the safe harbour which the men were at such pains to avoid and to void. They are the fruit of dry vines, shrivelled and rotten in no time at all. On their mattresses they are overcome by the desire for death. Their wives die by their own hand (or have to be given a helping hand by the