Male Sex Work and Society (39 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

6

A growing phenomenon is the organization of cyberbeats, where meetings for casual anonymous sex are organized through the Internet; see Mowlabocus (2008).

7

For further discussion on how sex at beats has been criminalized and regulated, see Dalton (2007, 2012) and Johnson (2010, 2012). For discussion of the differential regulation of heterosexual sex in public spaces, see Ashford (2012).

8

In Director of Public Prosecutions v. Bull (1994), there was an attempt to prosecute a male sex worker for soliciting; however, it was found that the term “common prostitute” originally used in the Street Offences Act 1957 (UK) only applied to females. The court relied on the Wolfenden Report on prostitution and found that the “mischief” the act was designed to address was a mischief created by women. For critique of this decision, see Diduck and Wilson (1997). The Policing and Crime Act 2009 (UK) replaced the term “common prostitute” with “person” to clarify that this offense applies to both males and females.

9

The licensing systems in Australia vary considerably between jurisdictions. New South Wales brothels are not criminalized or licensed but, rather, are subject to regulation through local government planning laws.

HIV/AIDS has had a significant impact on how we understand male sex work. The initial ambiguity surrounding HIV/AIDS—Where did it come from? What causes it? Who does and doesn’t it affect?—meant that it could have been characterized in a number of ways, but its being linked to sexually active gay men early in the epidemic meant that it was characterized as a sexually transmitted disease. The link between promiscuity and the risk of contracting HIV led to sex workers being identified as a problematic group—the possible vectors of transmission to the broader public

.

.

Before the HIV/AIDS epidemic, male sex work was rarely considered a public health problem. While sexually transmitted infections had long been associated with female sex workers, health professionals seemed unconcerned about the physical health of male sex workers and their clients. HIV/AIDS changed this, to some degree because at the time it appeared that a more fluid conception of human sexuality had emerged, which acknowledged that sexual practices were not equivalent to sexual identities. Bisexuality was viewed as putting people at risk of contracting the virus because male sex workers were thought to provide a bridge for infection between deviant and mainstream populations

.

.

What stands out for us in reading this chapter, along with some of the others in the book, is the evidence of the benefits in decriminalizing homosexuality and the sex industry. These moves promote proactive public health measures that create safer and more professional interactions between clients and workers, and between these groups and society. Societies that have adopted liberal reforms fare much better on a wider range of indictors compared with societies that remain punitive. The more liberal societies report less violence, safer and more productive client-worker interactions, and the development of a leisure sex industry that is both professional and responsible. In contrast, criminalization tends to drive the sex industry underground and leaves it open to criminal manipulation and poor health standards, which have an impact on everyone. The sex industry need not have such a dark underbelly

.

.

| Public Health Policy and Practice with Male Sex Workers | |

DAVID S. BIMBI JULINE A. KOKEN |

When male sex workers (MSWs) appear on the public’s radar, it often is in the form of an exposé of a public servant or a person with name recognition having hired a male sex worker. On the darker side, there have been numerous stories of men killed, often violently, by male sex workers or those the media labels as such. These sad stories typically involve an older man murdered by a young man he met online through a listserv or sex work website. Less focus is given to murdered sex workers, and it is a given that physical assaults perpetrated by a client on the MSW are greatly underreported. The public often reserves its sympathy for those forced into sex work through trafficking or other forms of coercion, but this compassion is primarily for women and children of both sexes, while adult males pressed into sex work receive much less attention.

Public exposés typically produce a great deal of comedy at the expense of the revealed transgressor. For example, late in the summer of the 2012 U.S. election season, the satirical website The Onion posted a story on the “Onion News Network” that focused on Tampa Bay-area male prostitutes gearing up for a flood of business during the Republican National Convention. Jokes about methamphetamine and unsafe sexual practices often serve as punch lines, indicating that the unhealthy aspects of male sex work are part of the public discourse. This reflects the fact that comedy often comes from uneasy truths.

In December 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2012) published a report focused on reducing HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among sex workers in low- and middle-income countries. It’s a safe assumption that these recommendations might address sexual health services, safer sex, and substance abuse. Part of the public discussion moving forward must also involve improving or maintaining good health among MSWs, as this group is disproportionately at risk for HIV infection and such efforts thus are in the best interests of both the public and the sex workers. In the United States, any use of government money to fund services related to sexuality has become a political battle zone; programs for sex workers provide good ammunition for those who oppose such efforts on moral grounds. In fact, the U.S. has had a decade-long antiprostitution requirement attached to receiving funding from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (Ditmore & Allman, 2013). Anyone receiving these funds is explicitly forbidden to “encourage, condone or promote prostitution.” This policy, known as the pledge, has resulted in the termination of programs, a phasing-out of services for sex workers, and the refusal by some to comply in order to receive U.S. funds (Ditmore & Allman, 2013).

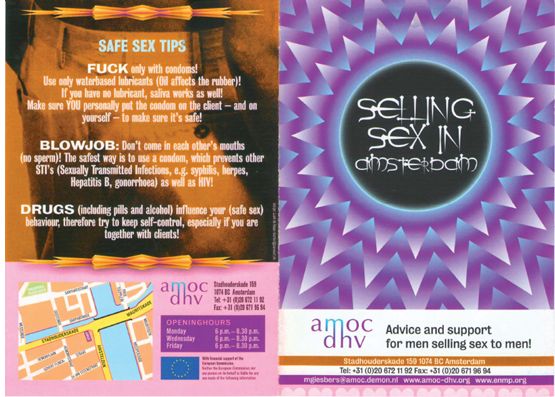

FIGURE 8.1

Front and back of a safe-sex pamphlet for male sex workers in Amsterdam, issued by the European Network Male Prostitution (ENMP). Copyright © ENMP/AMOC-DHV

Programs have been developed and implemented for male sex workers in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The European Union, funded by a multiyear grant from the European Network Male Prostitution (2002) to foster communication among those providing services for MSWs, published reports that included recommendations for public health policy and practice, social service programs, and other resources. The official recommendations echo those made in numerous other publications (Gaffney 2007; Parsons, Koken, & Bimbi, 2007; Smith & Seal, 2007; Williams, Bowen, Timpson, Ross, & Atkinson, 2006). More recently, the World Health Organization made its official recommendations, as mentioned above.

The WHO (2012) report calls above all for the decriminalization of sex work in order to improve the physical and emotional well-being of sex workers. Both legal and moral judgments have a long history of interfering with the implementation of and adherence to the best practices within the fields of public health and community health. Unfortunately, local politics, policies, and laws often intercede with moralistic arguments that prevent local public health professionals from designing and implementing programs for sex workers and their clients. More insidiously, antigay sentiments foster direct and indirect resistance to creating programs for MSWs and their clients, even though similar programs for female sex workers and their clients are already in place. Furthermore, as noted by Scott (2003), sex workers and their needs are viewed differently in accordance with their venue or mode of client solicitation (e.g., on the street, via Internet websites, and through real or virtual escort services). Street-based sex workers are viewed as deviants who are breaking the law and spreading disease, and thus are a problem for the criminal justice system due to community concerns about quality of life—that of local residents, not of the sex workers. Whereas indoor sex workers are more likely to be seen as victims of circumstance, financial or otherwise, and thus not viewed as criminals, they are nonetheless viewed as a public health problem.

Such stereotypes can hinder any effort to reach MSWs and improve their well-being. Homelessness, substance abuse, mental health needs (see

chapter 9

) are all problems sex workers experience, regardless of their “level.” Given the prevalence of HIV infection among populations of men who have sex with men in many areas of the world, MSWs clearly warrant competent, nonjudgmental services. Further public health programming should capitalize on male sex workers as a vector of sexual health education (Parsons et al., 2004) within the larger communities of gay and bisexual men who have sex with men.

chapter 9

) are all problems sex workers experience, regardless of their “level.” Given the prevalence of HIV infection among populations of men who have sex with men in many areas of the world, MSWs clearly warrant competent, nonjudgmental services. Further public health programming should capitalize on male sex workers as a vector of sexual health education (Parsons et al., 2004) within the larger communities of gay and bisexual men who have sex with men.

If they did not face structural barriers (e.g., the pledge) and ideological and moral biases (e.g., sex work is always bad), public health officials and community workers could develop effective services for MSWs and their clients. In many cases, both the client and the sex worker have the same needs: general sexual health, prevention of STI and HIV transmission, prevention of and treatment for substance abuse, and protection from violence. These concerns clearly have been recognized worldwide as public health issues, regardless of the cultural and social contexts of male sex work within localities, regions, and nations.

Background

There is a dearth of research into general or occupational health issues among MSWs; what is publicly disseminated typically focuses on sexual practices and drug use as they relate to HIV transmission (Bimbi, 2007; Browne & Minichiello, 1996; Minichiello, Scott, & Callander, 2013). Much of what is known about male sex workers in general and specifically about their unique health issues comes from researchers and health professionals who reach out to men on the street (Koken, Bimbi, Parsons, & Halkitis, 2004), most often within the context of HIV-related research (Bimbi, 2007; Minichiello et al., 2013; Scott, 2003).

The social stratification of sex work also dictates different needs among different types of sex workers. Men working the streets are more likely to be severely economically disadvantaged (e.g., homeless), struggle with drug abuse or addiction, not be gay identified, and may be more part of the overall “street scene” (Bimbi, 2007), whereas higher-end “escorts” are more likely to be gay identified and may have more interaction with the gay community in bars/clubs and social spaces in predominately gay neighborhoods. Therefore, in the absence of direct evidence, anecdotal evidence from the larger subculture (e.g., homeless youth, the gay male community) may be needed to inform any direct or indirect public health efforts.

Other books

Bething's Folly by Barbara Metzger

The Island by Elin Hilderbrand

Beauty and the Wolf by Lynn Richards

The Mugger by Ed McBain

The Alpha King by Vicktor Alexander

Fire Monks by Colleen Morton Busch

White Out by Michael W Clune

Lovelink by Tess Niland Kimber

At Last by Edward St. Aubyn