Male Sex Work and Society (41 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

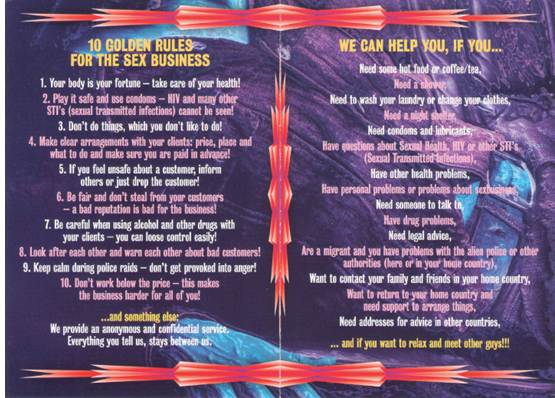

FIGURE 8.4

Pages from a pamphlet aimed at Swiss service providers to promote sexual health programs for male sex workers. Copyright © ENMP/Swiss AIDS Federation

Such approaches are reflected in two frameworks utilized in public and community health efforts. The Institute of Medicine (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994) has defined levels of intervention for the implementation of public health programs: universal interventions target an entire population or community; selective interventions narrow the focus to those who may be at risk; and indicated interventions are aimed at those with demonstrated risk. Clearly these levels address the “who” and thus leave the “what,” as in what are the goals of the interventions.

Another framework (Commission on Chronic Illness, 1957) for goal-setting in public health prevention is more focused on the “what,” which is as follows: primary prevention includes activities and efforts aimed at preventing health problems before they develop (onset); secondary prevention focuses on early detection of problems through screenings (e.g., STI testing), followed by appropriate follow-up, which may include harm-reduction strategies to reduce the likelihood of long-term poor health outcomes; and tertiary preventions involve the treatment of health problems and promote improved quality of life for those with health problems.

These two frameworks clearly raise the question of which to use and when integration may permit public health professionals, community-based organizations, and government entities to reach more persons in need. These frameworks have been integrated and adapted or revised, often in response to pedagogical critiques (Kutash, Duchnowski, & Lynn, 2006). The following proposes a similar new framework based on blending or collapsing the levels of intervention and prevention. In the Institute of Medicine’s levels of intervention, selective and indicated interventions target at-risk individuals, while the primary and secondary levels both include the goal of harm reduction. Therefore, each of the aforementioned pairs could be collapsed to simplify the model.

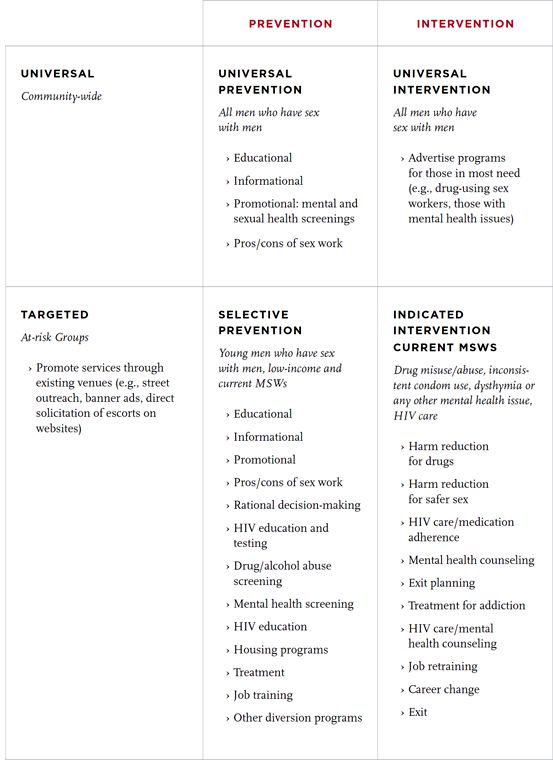

Table 8.1

provides a general idea of how the levels could be combined in a more manageable 2x2 matrix, based on scope (broad, targeted) and goal (prevention versus intervention). This may permit better use of limited resources and more effective outreach, with increased community participation (e.g., men getting the services they need). The following reviews the approaches, with examples and suggestions for programming.

Table 8.1

provides a general idea of how the levels could be combined in a more manageable 2x2 matrix, based on scope (broad, targeted) and goal (prevention versus intervention). This may permit better use of limited resources and more effective outreach, with increased community participation (e.g., men getting the services they need). The following reviews the approaches, with examples and suggestions for programming.

Universal Prevention

Any effort to reach out to male sex workers through the wider gay community would be a type of universal prevention. In many parts of the world, there is not one “gay community” but several, based on cultural and social interests, which might further complicate broad implementation. Nevertheless, there are some places of intersection, frequently the local gay media (newspapers, party papers, local websites), many of which may feature listings or advertisements for escorts, companions, body workers, etc. Many gay media proprietors offer reduced advertising fees or waive them altogether for public health promotions. In many areas, the webmasters and owners of websites and, more recently, mobile applications for dating or “hooking up” may include links to local health departments or to websites featuring sexual health information. Some also allow direct messaging to site users, as well as banner ads for programs and services.

Many nations have various listservs, such as Craigslist in the United States, that contain message boards frequented by sex workers. Due to legal issues, most listservs for broad audiences prohibit sex work posts. Coded language is therefore the norm, such as “looking for a generous man.” These listservs clearly can be employed in universal prevention programs with regular postings. Whether in print or at online forums, ads targeting MSWs would also reach the entire readership community and thus, if the ads had a professional, nonjudgmental tone, could help reduce the stigma of sex work. Even within a community with more positive attitudes about sex work (Bimbi, 2007; Koken et al., 2004), MSWs still experience stigma, prejudice, and judgmental attitudes about prostitution.

TABLE 8.1

Levels of Intervention x Levels of Prevention

The goal of universal prevention would be to educate all men about the pros and cons of being a sex worker. This would also include the promotion of sexual health care, testing and treatment for HIV, as well as mental health screenings. Education about substance abuse is also clearly warranted. The potential risks of engaging in sex work should be included, but not framed in a judgmental or fear-based tone, as this might drive men away from participating in a program or working with a particular agency. Nevertheless, it is strongly advised that the actual content and images be developed with the input of a broad selection of sex workers from local areas and target populations. Although the above discussion concerns media advertising, the same principals apply to direct outreach in terms of messaging and staff training.

Universal Intervention

The implementation of universal interventions would be very similar to universal preventions but with the narrower goal of reaching sex workers who may be in need. Health promotion would focus on creating awareness of programs focused on problem areas, such as substance abuse, mental health, housing, etc. Such programs may be sex-worker specific or open to all gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Selective Prevention

Selective prevention narrows the focus to places where sex workers are definitely present. Specifically, websites that permit escort listings and escort-specific websites are clearly targets for messages and service promotion. There also may be population subgroups, such as homeless youth and youth-centric cultural scenes, that outreach workers can target. The message and promotion are focused on prevention, such as health screenings and tips for sex worker safety.

Indicated Intervention

As with selective prevention, the focus narrows to places in which some sex workers present are clearly at risk. The goal is to help individuals access the help they need. This may involve direct outreach to drug-using sex workers, HIV positive sex workers, homeless sex workers, etc. Interveners must be aware that drug use, homelessness, and HIV are not discrete problems and may be interrelated with other mental health conditions.

Conclusion

A word of caution: any program, outreach effort, or services that do not address the needs of sex workers will most likely be a resounding failure. Case in point: the Coalition Advocating Safer Hustling (CASH) was funded by the American Foundation for AIDS Research through a grant to the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York City during the mid-1990s. There was a clear clash between the sex workers involved with the program and agency staff concerning the governance and mission of CASH (Boles & Elifson, 1998). The sex workers were more interested in an advocacy organization with broad goals, whereas the community-based organization sponsoring CASH was mostly concerned about HIV prevention.

Furthermore, any programs that explicitly serve gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men must also provide services that are culturally appropriate to meet the needs of sex workers within these populations (Gaffney, 2010). Many higher-earning male (as well as female and transgender) sex workers (or “escorts”) will not access services that primarily target street-based sex workers. Therefore, it is imperative that service providers address the needs of sex workers and clients as part of serving gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men from various communities. This will be accomplished most easily with providers who cater to the gay community or those within urban centers, whereas service providers outside of urban centers might not be prepared or open to serving these men. Even in the absence of structural barriers, there may be some reluctance to provide competent care to sex workers, for to do so may be viewed as “promoting” or “tolerating” prostitution. This chapter seeks to prompt thoughtful implementation of programs and services that will improve the sexual health of male sex workers. Finally, local providers are strongly urged to do their homework and identify problem areas or local trends in risk-taking, such as what party drugs are currently in vogue, as knowledge of their local sex work scene.

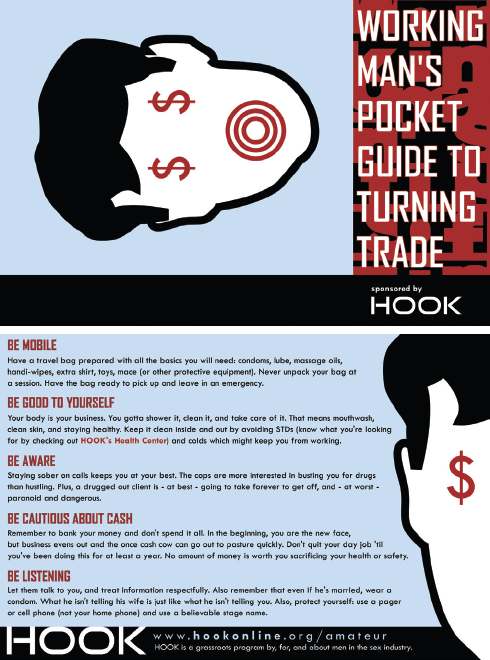

FIGURE 8.5

“Working Man’s Pocket Guide,” another handout from HOOK Online. Reprinted with permission from HOOK Online.

FIGURE 8.6

From the website of HOOK Online, Inc., a U.S.-based grassroots program that supports men who are or were involved in the sex-work industry.

References

Allman, D., & Myers, T. (1999). Male sex work and HIV/AIDS in Canada. In P. Aggleton (Ed.),

Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV

(pp. 61-81). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and HIV

(pp. 61-81). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Bimbi, D. S. (2007). Male prostitution: Pathology, paradigms and progress in research.

Journal of Homosexuality, 53

(1), 7-35. doi:10.1300/J082v53n01

Journal of Homosexuality, 53

(1), 7-35. doi:10.1300/J082v53n01

Bimbi, D. S., & Parsons, J. T. (2005). Barebacking among internet based male sex workers.

Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 9

(3/4), 85-105. doi:10.1300/J236v09n03

Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 9

(3/4), 85-105. doi:10.1300/J236v09n03

Other books

Mirrors by Eduardo Galeano

High Tide by Jude Deveraux

Spice by Seressia Glass

Condemned by John Nicholas Iannuzzi

The Spellsong War: The Second Book of the Spellsong Cycle by L. E. Modesitt Jr.

The Weavers of Saramyr by Chris Wooding

The Mammoth Book of Tasteless Jokes by E. Henry Thripshaw

The Gondola Maker by Morelli, Laura

Good for You by Tammara Webber

The Two Mrs. Abbotts by D. E. Stevenson