Male Sex Work and Society (70 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Up to 90 percent of MSWs in Germany currently are migrants (KISS, 2012), up from an estimated 55 percent in 2007 (Gille, 2007). The specific needs of migrant sex workers from Central and Eastern Europe have been noted for some years (European Network on Male Prostitution, 2003; Wright, 2003). The current majority is overwhelmingly from Bulgaria and Romania, which joined the EU in 2007, partly explaining the timing of the increase. In previous years the majority was from Poland and the Czech Republic, following these countries’ entry to the EU in 2004. Inclusion in the EU has meant increased opportunities to travel, which is especially attractive to those crossing borders in search of work. The increase in migrant MSWs in Germany must be viewed as a response to both economic opportunities and constraints, as noted earlier. Both countries of origin for the migrants discussed here—Bulgaria and Romania—have considerably poorer standards of living than neighboring member states, leading to continued outmigration. In addition, both have a large number of socially and economically marginalized citizens of Roma ethnicity, who, as a result of the recent enlargement of the EU, are now Europe’s largest and poorest ethnic minority. Thus, migration and willingness to engage in sex work should be understood as a reflection of social exclusion and poor economic conditions within the framework of a transnational political economy.

Thus, unique to the German situation is not only the fact that prostitution is a legal activity but that these migrant MSWs are not “illegal” because they are EU citizens. Nonetheless, while permitted to travel freely throughout the EU, at the time of this study most individuals from the new member states were not yet authorized to work in Germany because of transitional measures curbing access to national labor markets until 2014. Individual governments of countries already part of the EU, including Germany, were given the option to apply restrictions to workers from Bulgaria and Romania for up to seven years. As a result, these new EU citizens faced many everyday forms of exclusion, including unemployment, unequal relationships in the housing market, and difficulty accessing medical care. If they are no longer participating in the health insurance schemes of their home countries, they are ineligible for the European Health Insurance Card, which provides coverage in other member states. Migrant participation in home country health insurance is notably uneven, even though the coordination of social security schemes is part of the EU enlargement process. Evidence from daily practice suggests that it can be difficult to maintain insurance enrollment because of the financial burden and/or bureaucratic constraints, and this has resulted in noticeable health disparities among many migrants from the new EU member states living in Germany (Castañeda, 2011).

Notably, the recent influx of migrants to German cities has resulted in heightened competition among street sex workers in places like Frankfurt, where clients have reported being approached by up to eight boys at a time (Fiedler, 2011). This has resulted in lower prices, with many sex workers earning only 200-350 euros a month (US$260-$460). This has created antagonism between migrants and German sex workers, as evident from the following postings in an online forum: “Over here there are a lot of Romanians that have ruined business. They offer a cheap screw and ruin everything for us. I don’t have a problem with foreigners … but that is some real damage they are creating. A screw for five or ten euros, I wouldn’t do that and neither would anyone else.”

The Impetus to Migrate: Social Marginalization, Economic Constraints

It is implicitly understood and sometimes explicitly noted that most migrant MSWs in Germany today are of Roma ethnicity (KISS, 2012; Marikas, 2012; Subway, 2012; Unger & Gangarova, 2011). This is similar to other reports from NGOs across Europe (Gille, 2007). However, very few data reflect this trend. Germany does not collect “ethnic” data in official statistics, due to discomfort in dealing with these categories and strict privacy protection laws. Germany’s Federal Data Protection Act was one of the first of its kind and it continues to provide some of the highest levels of identity protection in Europe. This can be “readily accounted for by its past, and by suspicion concerning potential misuse of personal data, particularly by the state” (Simon, 2007, p. 56); thus the statistics collected on groups likely to face discrimination is a sensitive issue. There is an understanding that, if racial or ethnic stereotypes are the product of racism, then the use of such categories is likely to reinforce discrimination and create visible divisions, which works against integration efforts. In Germany, “there is no public debate on the statistics, which are discussed only by some NGOs and scientific experts. The organisations which represent ethnic minorities are generally very reluctant to tackle the question, an example being the Roma organisations, which are suspicious … of the use to which statistics may be put” (Simon, 2007, p. 57). As a result, to avoid contributing to the stigma of already marginalized groups, most organizations serving migrant MSWs do not collect data on ethnicity. On the other hand, it is also understood that they migrated away from their home countries precisely because of ethnic marginalization. The result is an implicitly understood target group, without sufficient information about exactly who is included. While understandable, given Germany’s recent history, this lack of data may also result in a lack of accounting for actual patterns of de facto racial or ethnic discrimination.

How do these young men self-identify? When asked, a minority identify as Rom or Roma, or use descriptors such as

Zigeuner

(gypsy) or Romanian gypsy, but most embrace a national identity and simply identify as Romanian or Bulgarian. Because of their ethnic minority background, many Bulgarian Roma speak a variant of Turkish and thus often describe themselves as Turkish or of mixed Bulgarian, Turkish, and/or Roma ethnicity. Indeed, being considered Turkish in some parts of Germany gives them benefits in the social hierarchy of immigrants in which Turks have ascended to become the “model minority” and are considered highly entrepreneurial and active in local politics. As one 18-year-old told me, “Pretending to be Turkish makes you not as obvious in Berlin.” By contrast, Roma face the same negative stereotypes in Germany that they do in their home countries. This flexible practice of self-identification—pretending to be Turkish—is an example of how marginalized groups can actively use and control local ethnic/national hierarchies in transnational settings.

Zigeuner

(gypsy) or Romanian gypsy, but most embrace a national identity and simply identify as Romanian or Bulgarian. Because of their ethnic minority background, many Bulgarian Roma speak a variant of Turkish and thus often describe themselves as Turkish or of mixed Bulgarian, Turkish, and/or Roma ethnicity. Indeed, being considered Turkish in some parts of Germany gives them benefits in the social hierarchy of immigrants in which Turks have ascended to become the “model minority” and are considered highly entrepreneurial and active in local politics. As one 18-year-old told me, “Pretending to be Turkish makes you not as obvious in Berlin.” By contrast, Roma face the same negative stereotypes in Germany that they do in their home countries. This flexible practice of self-identification—pretending to be Turkish—is an example of how marginalized groups can actively use and control local ethnic/national hierarchies in transnational settings.

By all accounts, these young men are between 17 and 30, with an average age of 21. Most are from the same regions of Bulgaria and Romania and know one other, often working alongside cousins and friends. Many migrate back and forth to their home country, where they may have a wife and children, or they bring their wives and children to Germany. Some report spending several months at a time in other countries (e.g., Italy, Spain, or France), and their family members may be spread out across Europe. One social worker described a village in northeastern Romania where poverty is extremely high and almost all the young men have left for sex work in Germany. He noted, “There is no concept of a ‘career’ as a hustler; it is not their career goal.” Rather, it is viewed as a temporary move before finding a job in another industry, such as construction. However, the transitional measures restricting employment, coupled with a lack of education and job skills, means that work opportunities for these men are largely out of reach. Upon arriving in Germany, they remain relatively isolated, rarely leaving the neighborhoods in which they live or work. Most are unfamiliar with the city and its geography, making it difficult to register officially or interact with authorities; they often pay unscrupulous brokers several hundred euros to help them with these tasks. Living conditions are often extremely poor; as many as ten young men may share an illegally sublet room. Some are illiterate and most have limited German skills, even though they are multilingual, having grown up speaking Turkish or Romanes at home and Bulgarian or Romanian in other settings.

Motivations to migrate often include a quest for “a little bit big money” to pay for a modest used car or begin construction on a house in Romania, or just to get a little spending money for needs and desires beyond daily sustenance (Gille, 2007). The wish to buy or construct a house in the home country is common and implies independence, and being able to provide an economic buffer for the family. However, they may have multiple goals or their goals may shift over time, and many young men adopt a new identity and habits of consumption in Germany in order to adapt to their lifestyle. These include a distinctly globalized social construction of masculinity and incorporating a range of imported fashions, identities, behaviors (Padilla, 2007). As described in the opening vignette, “swag”—propelled into the lexicon of contemporary German through pop culture and designated 2011 “word of the year” by dictionary company Langenscheidt—is adopted in attitude and clothing styles. However, swag and designer clothes, as I note, contrast markedly with simultaneous experiences of real deprivation, such as the collection of used cigarette butts and homelessness. While many young men are driven into sex work because of poverty, they rarely accumulate or remit money, often spending any earnings immediately. A popular way to spend money is on apps for mobile phones or gambling on tabletop slot machines. There has been an explosion of casinos and gaming halls in the past several years, especially in heavily migrant districts of Berlin such as Wedding and Neukölln. Interestingly, the young MSWs say they never played these machines in their home countries, only in Berlin. “For them, it is dirty money, so when they make money from sex, they spend it immediately. They are addicted to gambling or drugs, or they buy new clothes, so the next day they have nothing and have to go back to work” (Dowling, 2011).

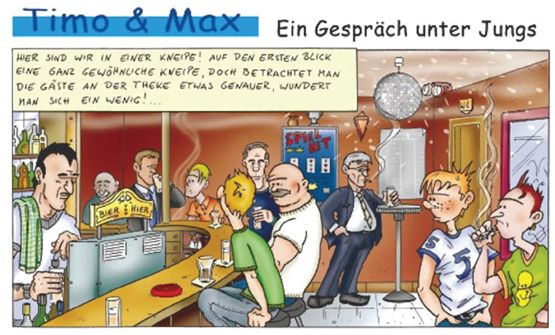

FIGURE 16.2

“A conversation among boys”: Comic strip created by the German male sex work support organization LOOKS eV.

While this group may appear to have few advocates, nonprofit organizations in several major cities provide assistance specifically to MSWs. While not united over the terminology used to describe their clientele, many employ the German term

Jungs

(boys or guys) to avoid the stigma attached to the

Stricher

(hustler) label, which has an explicitly sexual connotation. Jungs is a more neutral and “generally recognized term” in the scene (Subway, 2012) and sometimes is used as a self-descriptor (LOOKS, 2012). Other organizations use Stricher precisely because of its precision and everyday use, or simply refer to the clientele as male prostitutes. The increasing number of MSWs from Bulgaria and Romania has presented new challenges for these organizations, which were not initially focused on migrants (KISS, 2012; LOOKS, 2012; Marikas, 2012; Unger & Gangarova, 2011). Most of these projects started in the early to mid-1990s and remain largely funded by municipal HIV prevention monies (Wright, 2003). They offer a combination of drop-in center and street work outreach. According to reports from 2011, drop-in centers in each city served between 200 and 500 sex workers annually, an increase over previous years. In the drop-in centers, clients can eat, wash clothes, shower, shave, use Wi-Fi, relax, play games, and store belongings. Most also offer sleeping accommodations during the day, as many of the young men are homeless and generally are excluded from traditional shelters because of their migrant status, or they avoid them because they feel they are hostile settings. Social work consultations—when possible, in the client’s native tongue—provide advice on work-related concerns, illness prevention and health, dealing with government offices, housing, sexual identity, mental health, family relationships, debt, and getting out of prostitution. Finally, most of these organizations also provide weekly medical consultations (discussed in more detail below) in conjunction with the local health department or volunteer physicians.

Jungs

(boys or guys) to avoid the stigma attached to the

Stricher

(hustler) label, which has an explicitly sexual connotation. Jungs is a more neutral and “generally recognized term” in the scene (Subway, 2012) and sometimes is used as a self-descriptor (LOOKS, 2012). Other organizations use Stricher precisely because of its precision and everyday use, or simply refer to the clientele as male prostitutes. The increasing number of MSWs from Bulgaria and Romania has presented new challenges for these organizations, which were not initially focused on migrants (KISS, 2012; LOOKS, 2012; Marikas, 2012; Unger & Gangarova, 2011). Most of these projects started in the early to mid-1990s and remain largely funded by municipal HIV prevention monies (Wright, 2003). They offer a combination of drop-in center and street work outreach. According to reports from 2011, drop-in centers in each city served between 200 and 500 sex workers annually, an increase over previous years. In the drop-in centers, clients can eat, wash clothes, shower, shave, use Wi-Fi, relax, play games, and store belongings. Most also offer sleeping accommodations during the day, as many of the young men are homeless and generally are excluded from traditional shelters because of their migrant status, or they avoid them because they feel they are hostile settings. Social work consultations—when possible, in the client’s native tongue—provide advice on work-related concerns, illness prevention and health, dealing with government offices, housing, sexual identity, mental health, family relationships, debt, and getting out of prostitution. Finally, most of these organizations also provide weekly medical consultations (discussed in more detail below) in conjunction with the local health department or volunteer physicians.

Regular street work outreach is important because the street hustling scene shifts often and “no collective consciousness has emerged” (KISS, 2012, p. 13), which is unlike many other subcultures. Outreach workers’ activities consist of visiting cruising areas at night to inform sex workers about services, and to distribute health information, condoms, and lubricants. Outreach also involves one-on-one conversations as well as more sophisticated tools, such as a Bluetooth application to distribute health information to mobile phones. Bar and club owners and their staff are generally supportive of outreach efforts, and many agree to post information or keep free condoms available for those who ask. Novel prevention efforts to emerge in recent years include Internet chats, peer health promoters, and community mapping activities that allow men to exchange experiences and locate social and health services (Unger & Gangarova, 2011). However, outreach has been negatively impacted by the introduction of restricted areas that prohibit public prostitution in certain locations outside of designated red-light districts or “toleration zones.” The implementation of restricted areas that encompass entire cities has consequences for prevention and outreach efforts, since prostitution continues in these cities in hidden locations. This worsens the situation for nonprofessional MSWs, as they face risks associated with law enforcement, have less power to negotiate with clients, and become more difficult for outreach workers to locate (Unger & Gangarova, 2011).

Other books

Miss Silver Comes To Stay by Wentworth, Patricia

Astra by Grace Livingston Hill

Chained by Jaimie Roberts

Ceasefire by Black, Scarlett

This Hero for Hire by Cynthia Thomason

Captain's Day by Terry Ravenscroft

His Ever After (Love Square) by Ingro, Jessica

Silver Eyes by Nicole Luiken

Charlotte and the Starlet 2 by Dave Warner

Billy Phelan's Greatest Game by William Kennedy