Male Sex Work and Society (74 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

With the advent of the Internet, a new venue for male sex work has emerged. The ease, availability, and relatively low cost of advertising for commercial male-to-male sex work has led to the increased use of this venue by male sex workers … The dearth of research on this diverse population of Internet-based workers has resulted in a body of literature that has been inappropriately generalized to all men who are paid for sex as a group. (p. 14)

Logan (2010), using data from one of the largest online escort websites in the United States, adopted a hedonic regression method to ascertain which characteristics of US-based MSWs affect the price of their services. He found, for example, that “muscular men enjoy a premium in the market, while overweight and thin men face a penalty, which is consistent with hegemonic masculinity and the literature on body and sexuality” (p. 697). In another quantitative but more descriptive analysis of online male sex workers, Pruitt (2005) provides data gleaned from advertisements on the

Escorts4u.com

website to highlight the profile of male escorts in terms of two general sociological markers (i.e., age and race), sexual roles (e.g., top, versatile top, versatile, versatile bottom, bottom), escort agency affiliation, availability to travel, and male endowment. Pruitt argues that this latter variable is an important attribute for some clients in selecting an escort, which resonates with claims by Logan (2010) about the role of hegemonic masculinity in influencing demand for MSWs and the prices they charge.

Escorts4u.com

website to highlight the profile of male escorts in terms of two general sociological markers (i.e., age and race), sexual roles (e.g., top, versatile top, versatile, versatile bottom, bottom), escort agency affiliation, availability to travel, and male endowment. Pruitt argues that this latter variable is an important attribute for some clients in selecting an escort, which resonates with claims by Logan (2010) about the role of hegemonic masculinity in influencing demand for MSWs and the prices they charge.

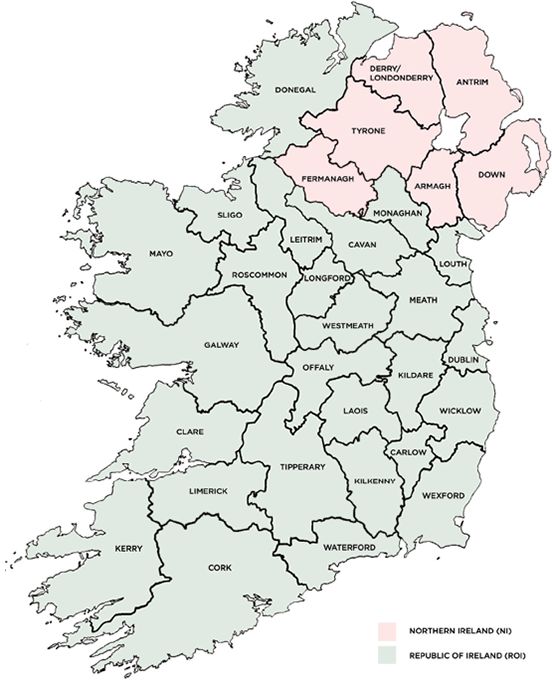

FIGURE 17.1

Map of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (pink).

In Ireland, academic policy and advocacy research have tended to focus almost exclusively on female sex work (Department of Justice [Northern Ireland], 2010; Hawthorne, 2011; Immigrant Council of Ireland, 2009; Ward, 2010). This gender bias rings true in an international context, where Weitzer (2011a) notes that “traditionally, scholars have focused their attention on female prostitution and have ignored male and transgender prostitution” (p. 378). Within a policy context, Whowell (2010) notes that “although sex-work policy in England and Wales purports gender neutrality, men rarely feature in policy documents as sex workers” (p. 127). This has certainly been the case in the recent political and policy reviews of sex work and trafficking for sexual exploitation in NI and the ROI, where MSWs have been largely left out of the policy debates. Indeed, the language used in a bill proposed before the Northern Ireland Assembly to criminalize paying for sexual services assumes the seller always to be female and the purchaser always to be male.

This chapter first seeks to lift the lid on the regulatory landscape—formal and informal—that governs male sex work in Ireland, and secondly provides some information about the characteristics of MSWs in the jurisdiction, such as number involved, nationality, age profile, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, and the geographic locations where MSWs offer their services. As is the case elsewhere, the development of the Internet has fundamentally changed the way sexual commerce is transacted in Ireland, including by male sex workers. Consequently, the bulk of our analysis draws from data obtained from one of the largest online escort websites—

http://www.Escort-Ireland.com

—which is used by sex workers who work in both parts of Ireland. We draw from data for the period 2009-2012, although to keep our discussion as contemporary as possible we focus on the most recent trends in the data. Since the Internet has not entirely displaced more traditional mechanisms for transacting sexual commerce, we also provide a brief comparative overview of the street-based male commercial sector in two of Ireland’s largest cities, Belfast and Dublin. While this sector remains small in both cities, it nevertheless merits discussion, if only to highlight some important differences in the characteristics of those involved in online and street-based sexual commerce. However, our discussion does not consider MSWs who may transact business in other indoor environments, such as gay clubs and saunas. Where possible we provide comparative data on female, transsexual, and transvestite sex workers in order to highlight similarities and differences across different segments of the Irish sex worker industry.

http://www.Escort-Ireland.com

—which is used by sex workers who work in both parts of Ireland. We draw from data for the period 2009-2012, although to keep our discussion as contemporary as possible we focus on the most recent trends in the data. Since the Internet has not entirely displaced more traditional mechanisms for transacting sexual commerce, we also provide a brief comparative overview of the street-based male commercial sector in two of Ireland’s largest cities, Belfast and Dublin. While this sector remains small in both cities, it nevertheless merits discussion, if only to highlight some important differences in the characteristics of those involved in online and street-based sexual commerce. However, our discussion does not consider MSWs who may transact business in other indoor environments, such as gay clubs and saunas. Where possible we provide comparative data on female, transsexual, and transvestite sex workers in order to highlight similarities and differences across different segments of the Irish sex worker industry.

It is important to note that the data presented herein are not statistically generalizable to the wider sex worker populations who live and work in Ireland. As is widely acknowledged in academic and policy circles, the true size of the sex worker population can never be ascertained with complete certainty, even in fully legalized environments, because of the stigma and contentious legal status that generally surrounds commercial sex (Sanders, 2005). Nevertheless, given the low preponderance of street-based sex work in both NI and the ROI, online sex work represents a significant facet of the sex work industry in Ireland. The Houses of the Oireachtas

1

(2013a) notes that “indoor prostitution by ‘escorts’ has come to dominate prostitution in Ireland since the introduction of the Internet and mobile phones” (p. 19). As a severely neglected aspect of both academic and policy analyses of the sex work industry, the data we present on MSWs are designed to highlight how Irish sex work is structured around issues of gender, sexuality, and geography. Put simply, sex work is by no means a female-only, heteronormative, urban-centric profession. If anything, it is polymorphous, spatially mobile, and highly globalized.

1

(2013a) notes that “indoor prostitution by ‘escorts’ has come to dominate prostitution in Ireland since the introduction of the Internet and mobile phones” (p. 19). As a severely neglected aspect of both academic and policy analyses of the sex work industry, the data we present on MSWs are designed to highlight how Irish sex work is structured around issues of gender, sexuality, and geography. Put simply, sex work is by no means a female-only, heteronormative, urban-centric profession. If anything, it is polymorphous, spatially mobile, and highly globalized.

Let’s (Not) Talk about Sex(uality)

It is reasonable to state in broad terms that both NI and the ROI are somewhat conservative societies and polities. This was especially true during the 19

th

century and through to the mid-20

th

century when it came to matters of a sexual nature—abortion, sex education, homosexuality/lesbianism, sex before marriage, masturbation, use of condoms, children born out of wedlock, the sale of pornography, and prostitution (Ferriter, 2009). Inglis (2005) argues that conservative attitudes toward sex and sexuality in the ROI were largely the result of the Catholic Church having a “moral monopoly” over such matters, due to the influence it wielded within the polity, its effective control of the education system, and its command over society from the church altar. Kitchin and Lysaght (2004) echo similar views regarding the regulation of the sexual landscape in NI. They note that “from the nineteenth century onwards it is clear that both Catholicism and Protestantism have sought to discipline sexual behaviour, forging a power/knowledge monopoly on sexual morality and praxis” (p. 99). This coming together of Catholics and Protestants in NI on sexual matters is, on one level, a curious political alignment, given the long-running ethno-religious schisms that have prevailed between the country’s two dominant communities. Such schisms, however, are found to be moribund when it comes to sex and sexuality. Smyth (2006), for example, has noted that conservative Catholics and Protestants from political and activist backgrounds have found themselves sharing common moral ground on issues of reproduction and abortion.

th

century and through to the mid-20

th

century when it came to matters of a sexual nature—abortion, sex education, homosexuality/lesbianism, sex before marriage, masturbation, use of condoms, children born out of wedlock, the sale of pornography, and prostitution (Ferriter, 2009). Inglis (2005) argues that conservative attitudes toward sex and sexuality in the ROI were largely the result of the Catholic Church having a “moral monopoly” over such matters, due to the influence it wielded within the polity, its effective control of the education system, and its command over society from the church altar. Kitchin and Lysaght (2004) echo similar views regarding the regulation of the sexual landscape in NI. They note that “from the nineteenth century onwards it is clear that both Catholicism and Protestantism have sought to discipline sexual behaviour, forging a power/knowledge monopoly on sexual morality and praxis” (p. 99). This coming together of Catholics and Protestants in NI on sexual matters is, on one level, a curious political alignment, given the long-running ethno-religious schisms that have prevailed between the country’s two dominant communities. Such schisms, however, are found to be moribund when it comes to sex and sexuality. Smyth (2006), for example, has noted that conservative Catholics and Protestants from political and activist backgrounds have found themselves sharing common moral ground on issues of reproduction and abortion.

The conservative sexual regime (Inglis, 2005) that has tended to dominate Ireland, north and south, persisted well into the 20

th

century. For example, legislation to decriminalize homosexuality was finally introduced in NI in 1982, some 15 years after it had been made legal in England and Wales. It is important to note that decriminalization was secured despite a fierce campaign—Save Ulster from Sodomy—led by then-leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and head of the Free Presbyterian Church, the Reverend Ian Paisley. Moreover, it would be another 11 years (i.e., 1993) before homosexuality was decriminalized in the ROI.

th

century. For example, legislation to decriminalize homosexuality was finally introduced in NI in 1982, some 15 years after it had been made legal in England and Wales. It is important to note that decriminalization was secured despite a fierce campaign—Save Ulster from Sodomy—led by then-leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and head of the Free Presbyterian Church, the Reverend Ian Paisley. Moreover, it would be another 11 years (i.e., 1993) before homosexuality was decriminalized in the ROI.

A similar geographical and temporal pattern is identifiable in relation to sex shops and other adult entertainment venues, such as lap dancing clubs. Royle (1984) notes that the first sex shops in Ireland were established in NI, in Belfast. In fact, two sex shops in two very different parts of Belfast opened shortly after one another in August 1982. The first was located in a mainly residential and staunchly Protestant neighborhood on the Castlereagh Road in East Belfast. However, this shop closed down fairly quickly in the wake of public protests. The second shop was located on Gresham Street, a down-market retail district on the periphery of Belfast’s central business district. Gresham Street now houses about six sex shops, all of which are apparently operating illegally, in contravention of various local government bylaws. This has resulted in a protracted legal dispute between the Belfast City Council and business owners that remains unresolved.

2

Fallon (2012) notes that the first sex shop in the ROI opened in 1991 in Bray, a small town on the outskirts of Dublin. It was 1993 before the capital city, Dublin, had secured its first sex shop. It was located on Capel Street, which, like Gresham Street, has become home to more sex shops than any other street in Dublin.

2

Fallon (2012) notes that the first sex shop in the ROI opened in 1991 in Bray, a small town on the outskirts of Dublin. It was 1993 before the capital city, Dublin, had secured its first sex shop. It was located on Capel Street, which, like Gresham Street, has become home to more sex shops than any other street in Dublin.

The Immigrant Council of Ireland (ICI, 2009), as part of its report into trafficking and the prostitution of migrant women in Ireland, claimed that there were 34 sex shops throughout the ROI, with 50 percent of them located within Dublin. The ICI noted further that there were also 27 strip clubs or lap-dance venues across Ireland, 15 in Dublin alone. No strip clubs currently exist in NI, although one did operate for a time in 2002-2003. Again, this commercial sex venue faced opposition from mainly Protestant religious groups that maintained a persistent public protest outside the shop in an effort to shame workers and patrons. Of course, it is not only the commercial sex sector that has attracted protests. The provision of family planning advice and services has also attracted considerable opposition from religious and pro-life groups in both parts of Ireland. To this day, public protests are held outside the offices of the Family Planning Association in Belfast.

Nevertheless, compared to what went before, Irish society—in both north and south—has seen a tremendous period of liberalization since the latter half of the 20

th

century, a process that was accelerated by the once roaring but now muted “Celtic Tiger” economy:

3

th

century, a process that was accelerated by the once roaring but now muted “Celtic Tiger” economy:

3

Over the last fifty years we have moved in Ireland from a Catholic culture of self-abnegation in which sexual pleasure and desire were repressed, to a culture of consumption and self-indulgence in which the fulfilment of pleasures and desires is emphasized. (Inglis, 2005, p. 11)

By the beginning of the twenty-first century Ireland seemed to be in the throes of a delayed sexual revolution, as a country long accustomed to a strict policing of sexual morality had carnally come of age. In conjunction with this, it became commonplace to satirise the values of earlier decades that had seemingly inhibited and repressed the libido of the Irish. (Ferriter, 2009, p. 1)

Despite this belated sexual revolution, political and social attitudes in Ireland toward particular forms of commercial sex, most notably prostitution or sex work, remain vociferously conservative. Like many nations throughout the world, sex work in and of itself is not an illegal activity within NI or the ROI. Northern Ireland’s Sexual Offences Order 2008

4

and the ROI’s Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993,

5

the two major pieces of legislation that currently govern sex work in both jurisdictions, do, however, make solicitation, curb-crawling, brothel-keeping, inciting, coercion, and controlling prostitution (i.e., pimping) illegal activities. Moreover, in the ROI it is an offense under the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act, 1994, for anyone to place an advertisement in an Irish-based newspaper or magazine, on television or radio, or to produce any form of publicity material (e.g., a poster, circular, or leaflet) that promotes the sale of sexual services via a brothel or as an independent sex worker or escort. These advertising restrictions were introduced in an effort to reduce the supply (and demand) of sexual services. This aim has been rendered redundant, however, by online escort websites such as

Escort-Ireland.com

, which is based in England and thus beyond the jurisdiction of the 1994 act. However, the development of technology in the commercial sex sector has caused particular consternation for some abolitionist groups. Ruhama (2012), one of the most vocal antiprostitution organizations in the ROI, has recently lobbied the Irish government to impose restrictions on the use of mobile phones by sex workers.

4

and the ROI’s Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993,

5

the two major pieces of legislation that currently govern sex work in both jurisdictions, do, however, make solicitation, curb-crawling, brothel-keeping, inciting, coercion, and controlling prostitution (i.e., pimping) illegal activities. Moreover, in the ROI it is an offense under the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act, 1994, for anyone to place an advertisement in an Irish-based newspaper or magazine, on television or radio, or to produce any form of publicity material (e.g., a poster, circular, or leaflet) that promotes the sale of sexual services via a brothel or as an independent sex worker or escort. These advertising restrictions were introduced in an effort to reduce the supply (and demand) of sexual services. This aim has been rendered redundant, however, by online escort websites such as

Escort-Ireland.com

, which is based in England and thus beyond the jurisdiction of the 1994 act. However, the development of technology in the commercial sex sector has caused particular consternation for some abolitionist groups. Ruhama (2012), one of the most vocal antiprostitution organizations in the ROI, has recently lobbied the Irish government to impose restrictions on the use of mobile phones by sex workers.

Since 2012 there have been moves to tighten the legislation regarding sex work in both NI and the ROI. In both jurisdictions the debate has largely been dominated by political and advocacy actors articulating either an oppression paradigm (Weitzer, 2010) or abolitionist positions (Wylie & Ward, 2012), which tend to see all sex work as “exploitative, violent, and perpetuating gender inequality” (Weitzer, 2011b, p. 666). From this standpoint, prostitution and human trafficking have been discursively framed as one and the same thing. This is reflected, for example, in a recent consultation paper—“Proposed Changes in the Law to Tackle Human Trafficking” (DUP, 2012)—and in the Human Trafficking and Exploitation (Further Provisions and Support for Victims) Bill that was introduced into the Northern Ireland Assembly by Lord Maurice Morrow of the DUP:

Other books

Faerie Winter by Janni Lee Simner

Izzy's River by Holly Webb

The Quest of the Missing Map by Carolyn G. Keene

All That Matters by Flagg, Shannon

Anno Zombus Year 1 (Book 4): April by Rowlands, Dave

Throne of Scars by Alaric Longward

Already Freakn' Mated by Eve Langlais

2. Darkness in the Blood Master copy MS 5 by Keire, Vicki

Trouble With the Truth (9781476793498) by Robinson, Edna