Male Sex Work and Society (52 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

Gaffney, J. (2007). A co-ordinated prostitution strategy and response to “Paying the Price”—but what about the men?

Community Safety Journal, 6

(1), 27.

Community Safety Journal, 6

(1), 27.

Gaffney, J. (2012, January).

The social organisation and contextualisation of male sex workers

. Paper presented at Birkbeck University, London, England.

The social organisation and contextualisation of male sex workers

. Paper presented at Birkbeck University, London, England.

Home Office. (2004).

Paying the price: A consultation paper on prostitution

. London: Author.

Paying the price: A consultation paper on prostitution

. London: Author.

Home Office. (2006).

A co-ordinated prostitution strategy and summary of responses to “Paying the Price.”

London: Author.

A co-ordinated prostitution strategy and summary of responses to “Paying the Price.”

London: Author.

Home Office. (2012).

A review of effective practice in responding to prostitution

. London: Author.

A review of effective practice in responding to prostitution

. London: Author.

Irving, A., & Laing, M. (2013).

Male action project: Summary of outcomes report for the Cyrenians, Millfield House Trust and Northern Rock Foundation

. Newcastle, England: Northumbria University.

Male action project: Summary of outcomes report for the Cyrenians, Millfield House Trust and Northern Rock Foundation

. Newcastle, England: Northumbria University.

Kingston, S. (2009). Demonising desire: Men who buy sex and prostitution policy in the UK.

Research for Sex Work Journal, 11

, 13.

Research for Sex Work Journal, 11

, 13.

Kingston, S. (2010). Intent to criminalize: Men who buy sex and prostitution policy in the UK. In T. Sanders, S. Kingston, & K. Hardy (Eds.),

New sociologies of sex work

(p. 23). Surrey, England: Ashgate.

New sociologies of sex work

(p. 23). Surrey, England: Ashgate.

Laing, M., Smith, N., & Pilcher, K. (in press).

Queer sex work

. Abingdon, England: Taylor & Francis.

Queer sex work

. Abingdon, England: Taylor & Francis.

Miller, H. (2005).

Prostitution, hustling, and sex work

. Retrieved July 1, 2009, from

http://www/a/EncyclopediaOfLGBTHistory/Prostitution-Hustling-Sex-Work/1129805

Prostitution, hustling, and sex work

. Retrieved July 1, 2009, from

http://www/a/EncyclopediaOfLGBTHistory/Prostitution-Hustling-Sex-Work/1129805

Sanders, T., O’Neill, M., & Pitcher, J. (2009).

Prostitution: Sex work, policy and politics

. London: Sage.

Prostitution: Sex work, policy and politics

. London: Sage.

Smith, N. (2012). Body issues: The political economy of male sex work.

Sexualities, 15

, 586.

Sexualities, 15

, 586.

Soothill, K., & Sanders, T. (2004). Calling the tune? Some observations on paying the price: A consultation on prostitution.

Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 15

(4), 64.

Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 15

(4), 64.

Thomas, J. (2000). Gay male video pornography: Past, present and future. In R. Weitzer (Ed.),

Sex for sale: Prostitution, pornography and the sex industry

(p. 49). London: Routledge.

Sex for sale: Prostitution, pornography and the sex industry

(p. 49). London: Routledge.

Weitzer, R. (2010). The mythology of prostitution: Advocacy research and public policy.

Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7

, 15.

Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7

, 15.

Whowell, M. (2010). Male sex work: Exploring regulation in England and Wales.

Journal of Law and Society, 37

, 125.

Journal of Law and Society, 37

, 125.

Whowell, M., & Gaffney, J. (2009). Male sex work in the UK: Forms, practices and policy implications. In J. Phoenix & J. Pearce (Eds.),

Regulating sex for sale: Prostitution policy reform in the UK

(p. 99). Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Regulating sex for sale: Prostitution policy reform in the UK

(p. 99). Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Wilcox, A., & Christmann, K. (2008). “Getting paid for sex is my kick”: A qualitative study of male sex workers. In G. Letherby, K. Williams, P. Birch, & M. Cain (Eds.),

Sex as crime

(p. 118). Devon, England: Willan.

Sex as crime

(p. 118). Devon, England: Willan.

Acknowledgments

This chapter is based on a presentation written and delivered by Justin Gaffney in January 2012 for Birkbeck University. The image used for the front cover of the “Sorted Men” guide (see

figure 11.1

) is the artwork of Will Barras for Scrawl Collective (

www.scrawlcollective.co.uk

); send all inquiries to

[email protected]

or telephone (44) 777-0888-104.

figure 11.1

) is the artwork of Will Barras for Scrawl Collective (

www.scrawlcollective.co.uk

); send all inquiries to

[email protected]

or telephone (44) 777-0888-104.

Endnotes

1

Although the men Atkins engaged with during his research sought to exchange sex and intimacy for money, goods, and services, he argues that the term “sex work” does not adequately describe the sometimes complex relationships between men (or “lads” as he describes them) and their clients.

Although the men Atkins engaged with during his research sought to exchange sex and intimacy for money, goods, and services, he argues that the term “sex work” does not adequately describe the sometimes complex relationships between men (or “lads” as he describes them) and their clients.

2

This chapter heading is adapted from Gaffney (2007).

This chapter heading is adapted from Gaffney (2007).

3

Although Brooks-Gordon (2006, pp. 46-47) notes that there were seven government reports published by four government committees on prostitution between 1928 and 1986, these were not considered in “Paying the Price” or the “National Strategy.”

Although Brooks-Gordon (2006, pp. 46-47) notes that there were seven government reports published by four government committees on prostitution between 1928 and 1986, these were not considered in “Paying the Price” or the “National Strategy.”

4

SohoBoyz was a social enterprise working with male and transgender sex workers in London from 2007 to 2010. It was a holistic service with a primary focus on training, development, and educational opportunities for men selling sex.

SohoBoyz was a social enterprise working with male and transgender sex workers in London from 2007 to 2010. It was a holistic service with a primary focus on training, development, and educational opportunities for men selling sex.

Because male sex work has been closely linked to male homosexuality, official reactions to male sex workers often mirror those to homosexuality. In geographic areas where male homosexuality is actively policed, such as in Africa, a two-tiered approach to male sex work has typically emerged in which clients are punished and the sex worker is subjected to welfare-based interventions and treatment. Prior to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, homosexual acts in Africa were policed on the basis that male sex work typically involved the abuse of younger men by older men. Following the appearance of HIV/AIDS, regulation of male sex work in Africa was instead justified on the basis of a public health crisis. While there were calls for draconian interventions, including the quarantine (essentially imprisonment) of at-risk populations, some public health interventions in Africa adopted a more liberal approach, which relied on individuals and communities to take responsibility for their own health care. Health officials attempted to devise strategies for disease control that included the participation of communities (real and imagined) that the virus affected. This voluntarism approach to the problem of HIV/AIDS was supported by many gay leaders, civil libertarians, physicians, and public health officials, who demanded that education provide the central, if not sole, response to the virus

.

.

| Male Sex Work in Southern and Eastern Africa | |

PAUL BOYCE GORDON ISAACS |

Background to the Research: Aims and Objectives

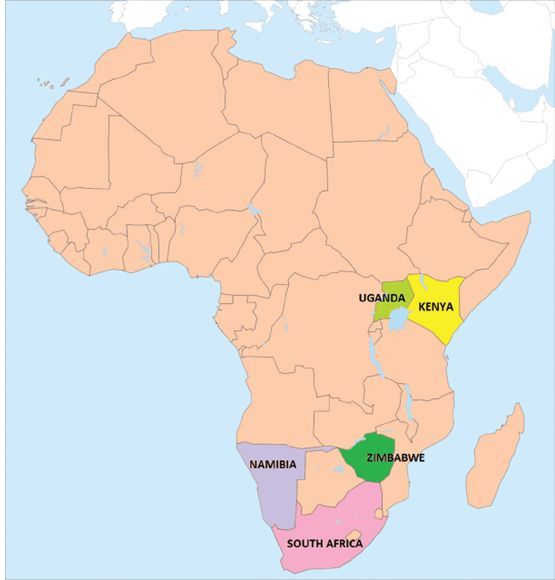

The aim of the present study was to explore the social contexts, life experiences, vulnerabilities, and sexual risks experienced by men who sell sex in Southern and Eastern Africa, with a focus on five countries: Kenya, Namibia, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. These issues were explored in the context of a participatory workshop and focused groups conducted with male sex workers (MSWs). Held in Johannesburg in December 2011, the workshop was underpinned by a definition of MSWs as “any man who accepts money or goods [favor, reward, value] in exchange for sex with another man” (Kellerman et al., 2009). The aim was to explore personal life stories as a way to achieve an understanding of the subjective circumstances and experiences of men who sell sex in these countries. We focused in particular on the experience of men who not only sold sex to other men but who, for the most part, self-identified with same-sex sexuality.

The work also sought to develop new and more effective means of representing MSWs through a respondent-driven approach, which included a seed/snowball method that involved follow-up work in Kenya and Namibia (Magnani et al., 2005). The MSWs who took part in the research represented different contexts on the African continent and a cross-section of personal experiences. They also were among those who might support and develop ongoing leadership for male sex workers in Africa. Against this background, our exploration included three distinct but overlapping areas:

Social contexts,

including the geographic and political contexts of male sex work.Sexual practices,

including sexual activities, roles, identities, and internal and external responses to the labels designating both men who have sex with men and male sex workers, as applied popularly and in HIV prevention work.Structural and personal risk factors,

including a range of themes related to personal and social responses to male sex work within the context of marginalization and human rights violations, the absence of explicitly protective laws, HIV and AIDS, substance abuse, sociopolitical influences, family, culture and taboos, religion, stigma/prejudice, internalized phobias, and legislation.

Other books

Sex Drive by Susan Lyons

Anna, Where Are You? by Wentworth, Patricia

Ark by K.B. Kofoed

A Clean Kill by Mike Stewart

Gone to Ground by John Harvey

A Sticky End by James Lear

The Saint vs Scotland Yard by Leslie Charteris

The Secret Apocalypse (Book 1) by Harden, James

Charity's Angel by Dallas Schulze

Blood of the Wicked by Karina Cooper